Founder of Peʻahi Big Wave contest retires, looks back at Maui surfing pioneers

By Gary Kubota

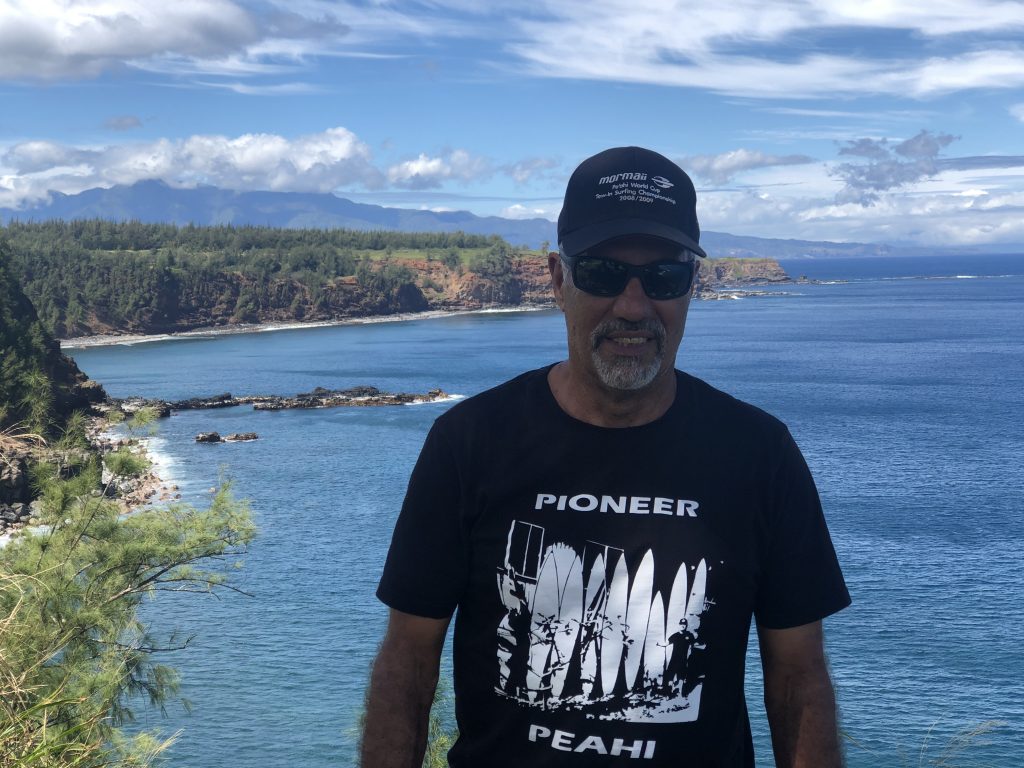

A People Of Maui Interview: Rodney Lash Nui Kilborn

Rodney Lash Nui Kilborn was a firefighter on Maui and had sponsored a number of amateur surfing events as a volunteer organizer on the Valley Isle, when he led a number of other watermen to help to start the first annual Peʻahi surfing contest in the mid-1990s, raising the awareness of the waves in excess of 30 feet at Peʻahi and tow-in surfing as a featured event.

The event eventually brought surfers from different countries and a millionaire co-sponsor from Brazil in 2001-2002. The millionaire sponsor didn’t stay long but the event has become a popular attraction for residents as well as visitors for more than two decades. The event has been televised in 30 countries.

Kilborn recently retired from being the organizer. He continues to serve as a volunteer adviser and is at the forefront of building an appreciation and the maintenance of Hawaiian place names for the surfing sites, including Peʻahi, which is sometimes called “Jaws,” ushering in fearful images as in the film Jaws about a killer shark.

Maui Now writer Gary Kubota interviewed Kilborn.

KUBOTA: Why is it important to promote Hawaiian place names such as Peʻahi for the surfing contest?

KILBORN: Peʻahi. It’s important to respect Hawaiian culture or any culture in the world. Our ancestors name the place because they had a connection spiritually with the area and had a connection with Peʻahi, her swirling ocean fan of breezes, sounds of crashing thunder that is music to the soul. When Peʻahi calms down, she draws you back to her peaceful energy. Hawaiian place names carry with them a meaning and often a deeper understanding of the area. It allows everyone to appreciate the subtleties and levels in Hawaiian culture. In the Hawaiian dictionary, Peʻahi means to beckon or wave. On a calm day from a bluff, you can see the bones of the reef extending along the coast like an open hand welcoming the ocean waves. As a waterman, it’s important to know the location of the reefs and currents and learn to go as much as possible in harmony with nature, in order to survive. In Hawaiian culture, the shark is an aumakua, a guardian god and friend for some families. We don’t look at the shark as an enemy.

KUBOTA: You mentioned that your father came from Maui? Please tell me a little bit about your family.

KILBORN: My father Harold James Kaleianuenue Kilborn was Hawaiian and was raised in Honokōwai in West Maui. He later moved to Oʻahu. My mother was Vivian DeSoto. I had great parents. Our family with three brothers and three sisters were raised on Oʻahu. We never had much money, but we were happy. My dad was a waterman when he was growing up and told us stories about diving for coins tossed by visitors on ships at Honolulu piers, hanging out in Waikīkī, and riding his Harley-Davidson. We were always in the ocean or rivers catching frogs to sell at Pearl City Tavern or just swimming.

KUBOTA: I guess surfing was quite different back then?

KILBORN: Yes. When I was 12, maybe 13, I used to borrow my father’s 10-foot balsa wood board. It was too freaking heavy. The board had a resin coat on it and weighed so much it took me and two other kids to carry it to the beach. We’d go to a place in ʻEwa Beach on Oʻahu called “Hau Bush.” When I was 16, I had a 9’6″ regular foam surfboard, a Harbor or Bing. I used to hang out with Pearl City guys — the Wicklund brothers and Craig Sugihara who later founded Town & Country Surf. We’d surf at a place called “Big Rights” at Ala Moana. Boards became a lot shorter in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Later, I began surfing larger waves on the North Shore. But it was always a challenge because there were too many surfers, more than 12 in a line-up. It was too crowded. I bought a VW camper and moved to Kauaʻi to work as a firefighter. I began surfing larger waves in west Kauaʻi near Barking Sands. My wife Cathy and I decided we’d like to live on Maui where we had ʻohana.

KUBOTA: What kind of equipment and support is needed to hold a Peʻahi event?

KILBORN: We usually have 14 jet skis for different reasons, including nine rescue jet skis. A helicopter is used for filming and rescue at some point. We also have medical boats with two doctors and two emergency medical technicians. Most surfers wear inflatable vest or wetsuits.

KUBOTA: What are the requirements for participation?

KILBORN: The Peʻahi big wave member board invites elite big wave surfers to the event, and yes, we have a lot of surfers wanting to be in the event, but when the waves are 20+ feet Hawaiian, there are very few that can handle it. Most big wave surfers train diligently all year round. With no turbulence in the ocean, they can hold their breath five minutes or littler longer, but with a heavy wipeout on a one wave hold down, the average is 12 seconds and with a two wave hold down, it’s 30 seconds. The time for holding breath under extreme conditions doesn’t sound like much, but it is.

KUBOTA: What challenges lie ahead for the sport of big-wave surfing at Peʻahi?

KILBORN: That’s a great question. We’ve established an interest for the Peʻahi competition and sponsors. But we continue to need state and county cooperation, including public safety in the ocean around the event, as well as safe highway access. When you have surf of 15 feet and above, you still need jet skis to tow out the surfers.

KUBOTA: There seems to be a lot more interest in surfing in terms of promotions and money for surfers, than surfing in the 1960s? Back then, surfing wasn’t an Olympic Sport and didn’t attract as many sponsors?

KILBORN: It’s great now for surfers who commit to the sport they love and can make a living. The downside of it, in these extreme big wave surfing sports, is the risk. Every heavy wipeout is like a car accident. lnjuries settle in, and it’s a short career, and we’re grateful for everybody’s kōkua in making it safer.

KUBOTA: Is it true you’ve arranged so that the Peʻahi contest never competes with the big wave Eddie Aikau event on Oʻahu?

KILBORN: Yes, it’s out of respect to the memory of Eddie Aikau and his family that we give organizers the first option to hold their contest. For us, the conditions at Peʻahi have to be right as well for the sake of safety.

KUBOTA: In what way?

KILBORN: Besides the size of the wave surge, the wind conditions have to be right. The winds can’t be too westerly — the surf’s not great then — or too Northerly, missing Peʻahi.

KUBOTA: How did you get involved in organizing surfing contests?

KILBORN: I began helping Imua Family Services, also known as Imua Rehab, to organize amateur contests in the 1980s. It was a way to give back to the community. The benefit was watching the smiles, watching the kids have fun. I’d call professional organizers like International Professional Surfing director Randy Rarick and surfer Gerry Lopez for advice.

We got into Hawaiʻi Surfing Association through its Oʻahu organizer Reed Inouye. His organization was on Oʻahu and our’s was on Maui. We were the first ones on Maui to have contests statewide in the late 1980s. We had a rating system. So out of all the divisions and contests we had, the top six from each division on Maui would be invited to go to Oʻahu for the state championship. Whatever money we made from the contest, we used that to go toward accommodation for the Maui kids.

Nelson Togioka from Kauaʻi started the contest on Kauaʻi and then the Big Island came in too. That’s before the students had high school competitions. That’s how it started. I did that for 19 years. Today, you got world class surfers coming out of Maui. It’s still going on. Organizers John and Donna Willard are doing it and doing a great job. I taught them how to do it.

KUBOTA: In a prior conversation, you mentioned individuals were beginning to surf at Peʻahi in the 1990s?

KILBORN: I’m not sure exactly when, maybe the 1980s? This is an area where a few guys paddled out to surf not bigger than 12 feet. Peʻahi starts to fully break at 15+ feet. From what I saw windsurfers started first to ride huge waves 15+ feet Hawaiian in the late 1980s.

Some professional windsurfers like Pete Cabrina and Laird Hamilton were taking on the surf at Peʻahi. Buzzy Kerbox who was a pioneer started being towed in by a Zodiac on some big days.

KUBOTA: Who helped you to organize the first Peʻahi surfing competition?

KILBORN: We did it out of love in 1996. It was all volunteers. No one including myself got paid. There were some big name surfers who also came from Oʻahu. There were no major sponsors. The winners received free pizza. We went up to my house, and I bought pizza for everybody. Some years later I picked up a Brazilian sponsor who paid $168,000 in prize money. A year later, state officials decided to not give me the exclusive permit after the Brazilian tried to get a permit. Instead, the state alternated the weeks of operation during the season between us. The waves were so small that season we never had a contest.

KUBOTA: How did you feel about the way the state handled the situation?

KILBORN: I felt I had been singled out by the state. My supporters including the Triple Crown Of Surfing pointed out that this kind of big wave contest required an expertise to keep competitors safe, similar to the Eddie Aikau big wave competition. Eventually, the state realized it had the wrong approach, and I was able to renew the Peʻahi competition. I wouldn’t have been able to continue to do this kind of work without the support of my family, especially my wife Catherine.