Lottery Officially Canceled for Hawaiian Immersion at Pāʻia

Kili Nāmauʻu, Director of Pūnana Leo o Maui, the Hawaiian immersion preschool program that serves as a feeder school for Pāʻia provided heated testimony at Tuesday’s planning meeting for Hawaiian Immersion at Pāʻia. Photo by Wendy Osher.

[flashvideo file=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xhhnU0zbi4c /] By Wendy Osher

A controversial lottery for admission into the Hawaiian Immersion kindergarten at Pāʻia Elementary School was officially canceled during a stakeholders meeting at the campus on Tuesday morning.

School Principal, Susan Alivado, who initiated the lottery, confirmed that it is not going to take place, after hearing criticism from immersion supporters claiming lack of communication and confusion surrounding the issue.

“What I don’t care for is there has been no communication for parents and especially the teachers,” said Kili Nāmauʻu, director of Pūnana Leo o Maui, the Hawaiian immersion preschool program that serves as a feeder school for Pāʻia.

School Principal, Susan Alivado, who initiated the lottery, confirmed that it is not going to take place. Photo by Wendy Osher.

Nāmauʻu, who also is a member of Nā Leo Kākoʻo O Maui, the nonprofit group for Ke Kula Kaiapuni o Maui (the Hawaiian Language Immersion Schools on Maui) said, “I can’t believe how teachers found out about the lottery through us, NOK (Nā Leo Kākoʻo O Maui). That is unacceptable. They were in shock.”

When asked for clarification, Principal Alivado said, “At this point, we don’t need a lottery. We’re accepting all students.”

When asked if there would be a letter going out to the student body, Alivado said, “I think it probably would be more efficient if I use the 21st century thing, and do a voice mail out to everybody.”

Pulama Collier, who has held various roles in the Hawaiian Immersion program since 1991, having taught at both Kalama and Kekaulike, also expressed concerns at the meeting. Photo by Wendy Osher.

She said the parents of keiki in Papa Mālaaʻo kindergarten program will be getting a call from the office asking them to enroll their child this week.

The accommodation comes despite earlier concerns of limited room for an overflow of students seeking geographic exceptions into the Hawaiian Immersion program.

The lottery would have limited the program to the first 40 names drawn, excluding 13 of the 53 applicants that sought admission into the program, and eliminating an additional number of students that missed the geographic exception deadline.

The issue prompted earlier demonstrations in which program supporters called the proposed lottery “divisive” and “discriminatory,” and argued that it threatened efforts to continue reviving the Hawaiian language.

Principal Alivado also issued a verbal apology at the meeting saying, “I feel badly that the keiki were impacted. I did have some parents come in and talk to me personally, so for that I would like to apologize. I wish I could have avoided that kind of a scenario.”

At Tuesday’s meeting, Principal Alivado confirmed that the school would now be expanding the Papa Mālaaʻo kindergarten program to three classes instead of two for the upcoming school year.

For the third grade, where there is also a heavy student-to-teacher ratio, school officials hope to hire two more immersion teachers so that they can separate reading and math from other subject areas.

“If I can pick up only one more kumu, then we will have a large third grade class. So, it all hinges on staffing. I know that there is definitely one candidate out there. I know we’re not the only school vying for that one candidate,” said Alivado.

She requested a list of viable candidates from meeting facilitators so that names could be shared with district personnel.

The meeting also included heated testimony from those within the Hawaiian Immersion community expressing dissatisfaction with what they called divisiveness and alleged treatment of the program.

That included scathing remarks from Nāmauʻu, who directed her comments toward Principal Alivado. “I’m sorry, but I don’t want you to just wash this over,” Nāmauʻu said.

“I know that there is this systemic problem: It’s a problem with the BOE (Board of Education); it’s a problem with the DOE (Department of Education); but you are the principal of this school,” said Nāmauʻu, who is also a parent of three children who have gone through the program by attending immersion programs at Pāʻia Elementary, Kalama Intermediate, and Kekaulike High School.

Nāmauʻu said she often gets calls from parents who want to send their child to immersion, but claim they are turned away. “You know, there’s never enough room at this school. I have to keep telling people, ‘You have to persevere.’

“I tell them on the phone, ‘They’re going to tell you “no,” but keep at it.’ Why do I need to enforce our people to do that? People don’t know any better, they just walk away. This is why we don’t have more people coming into this program–because they’ve never been given a chance,” Nāmauʻu claimed.

School administrators did not comment on Nāmauʻu’s testimony during the meeting, but instead answered specific questions posed by those in attendance and issues addressed by the meeting facilitator.

Pulama Collier, who has held various roles in the Hawaiian Immersion program since 1991, having taught at both Kalama and Kekaulike, also expressed concerns during testimony.

“Something is amiss. It is not the fact that we don’t have kālā (money); it is not the fact that we don’t have teachers—those are not the problems.”

Collier who has been teaching at Kekaulike since 1997 said, “We’ve had opportunities to grow; we’ve had teachers that wanted to (come)—yet that system that we’re in doesn’t allow for it.

“The challenge lies in attitudes,” said Collier of administrators. “They cannot be advocates for us because they don’t know.”

Collier said she feels as if the program is just being tolerated. “There is no lōkahi (unity) when we sit at the table,” she said. Collier used the opportunity to ask DOE and BOE officials in attendance to look at a larger picture that includes all of the immersion programs on Maui, not just the one at Pāʻia.

During the meeting, some supporters proposed the conversion of the entire school into one dedicated to Hawaiian Immersion, but with the next school year quickly approaching, the idea is one that officials say would need strategic planning and organization, and gave no formal position.

“I know we’re going to be taking over this school one day,” said Nāmauʻu. “We have to. We don’t have any other place to go. We have to grow this program here and I’m sorry for the English people, but they do have other choices.

“It’s been diluted over the last several years with always accommodating English, NCLB (No Child Left Behind), everything–it’s diluted our language, it’s diluted our values, it’s diluted everything, and we need to have a strong foundation, all-inclusive school for ourselves so we can practice our ʻōlelo, our language our culture, without having interference from others that don’t understand our program and do not embrace our program,” said Nāmauʻu.

“It’s been lacking here for years, and I’m just over that. We need to move on; we need to take over this school–that’s my short-term, (and) long-term solution for this process,” she said.

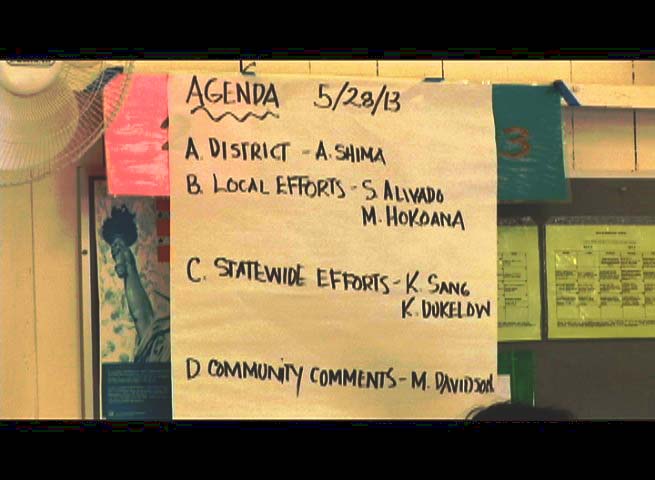

Both Alvin Shima from the Department of Education, who is serving a temporary role as the district superintendent, and Board of Education Maui Representative Wesley Lo were available to answer questions at the meeting.

“The issue is going to be how well we as a community come together and address the problems as opposed to being fragmented,” said Lo. “I think we would be better off if we start off with this opportunity to get a lot off our chest right now,” he said.

He continued saying, “There are short-term issues and it sounds like, between Principal Alivado and District Superintendent Shima, that the first thing was to deal with the lottery.”

While the lottery was ultimately canceled following heavy criticism, testimony was also received saying the controversy provided some positive outcomes by bringing the issue of expansion to the forefront.

Going forward, Lo said, “We need to now organize and start moving this thing forward on a more strategic basis to solve the long-term problems. It’s only a year away before we’re going to be facing this (expansion issue) again,” he said.

_1768613517521.webp)