Sunlight Shown to Affect Mercury Levels in Fish

By Dave Smith / Big Island Now

Researchers say opah, also known as moonfish, have higher concentrations of mercury because of where they feed. Photo by C. Anela Choy/UH.

Ocean researchers say they have solved part of the puzzle about mercury accumulations in the fish we eat.

Mercury, a common industrial toxin, is carried through the atmosphere before settling into the ocean and entering the marine food chain.

Several years ago, scientists at the University of Hawai‘i found that predatory fish like opah and swordfish that feed at deeper depths in the ocean had higher mercury concentrations than those, like mahi-mahi and yellowfin tuna, which feed closer to the surface.

“We knew this was true, but we didn’t know why,” Brian Popp, UH professor of geology and geophysics, said in a press release from the university.

A new study co-authored by Popp published this week in the journal “Nature Geoscience” sheds new light – no pun intended – on reasons why levels of mercury vary with depth.

Bacteria in the ocean change atmospheric mercury into the organic monomethylmercury that can accumulate in animal tissue. That is present in smaller fish and in turn accumulates in the larger predatory species.

However, analysis by researchers from UH and the University of Michigan found that chemical reactions driven by sunlight destroy up to 80% of a form of the element known as monomethylmercury in well-lit upper waters.

The research focused on levels of mercury in nine species of fish, six predators and three types of prey.

The findings built on previous research by Michigan scientists that up to 50% of the substance was destroyed by photochemical reactions off the shores of the Gulf of Mexico.

Hawaii’s conditions proved to be better for this type of analysis.

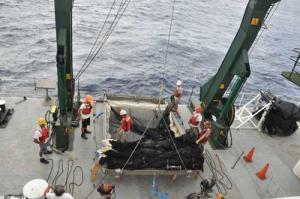

Researchers using nets to collect fish for a study on mercury concentrations. Photo by C. Anela Choy/UH.

“The crystal-clear waters surrounding Hawai‘i and the unique information that we had about the depths at which our local fish feed allowed us to clearly identify both the photochemical degradation of monomethylmercury at surface levels and the microbial production of monomethylmercury from inorganic mercury in deeper waters,” Popp said.

The finding that mercury is more available in its toxic form in the food chain at lower depths is important because scientists expect mercury levels at intermediate depths in the North Pacific to rise in coming decades, the researchers said.

Higher levels of mercury will mean higher levels in fish, according to Joel Blum of the University of Michigan, lead author on the new paper and a professor in the department of earth and environmental sciences.

“If we’re going to effectively reduce the mercury concentrations in open-ocean fish, we’re going to have to reduce global emissions of mercury, including emissions from places like China and India,” he said.

The research is particularly relevant here in Hawai‘i, the scientists say, where marine fish consumption is among the highest levels in the United States.

A study focusing on mercury concentration and fish consumption found women in Hawai‘i are three times more likely to have elevated umbilical cord blood mercury levels compared with the national average.

Scientists say the main pathway for human exposure to methylmercury is the consumption of large predatory marine fish such as swordfish and tuna.

Effects of methylmercury on humans can include damage to the central nervous system, the heart and the immune system. The developing brains of fetuses and young children are especially vulnerable.

Funding for the project was provided by the National Science Foundation, the University of Michigan’s John D. MacArthur Professorship, the Pelagic Fisheries Research Program at the University of Hawai‘i, and University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant.