Rally speaks out against proposed mosquito release on Maui to battle avian malaria

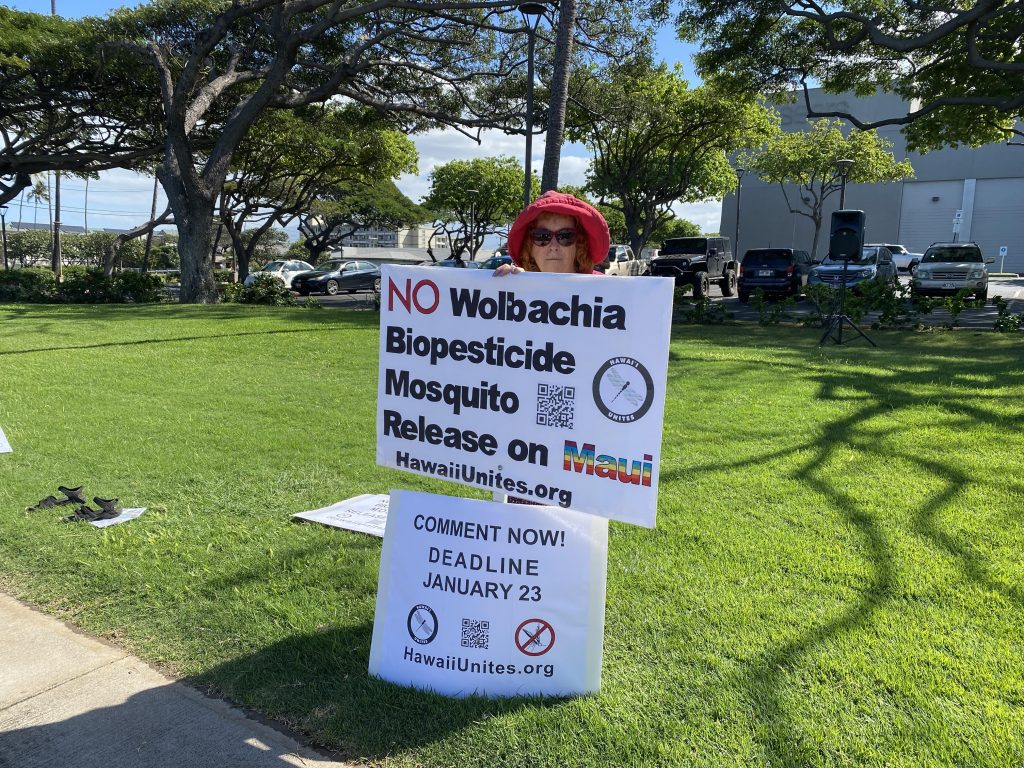

A sign waving rally was held Saturday in Kahului, asking the state to complete a full Environmental Impact Statement for their planned “Mosquito Control Research Using Wolbachia-based Incompatible Insect Technique” project.

The two hour rally was held along Kaʻahumanu Avenue and drew an estimated 60 participants, according to organizers from the environmental group HawaiiUnites.org.

Founder Tina Lia said the event was organized to bringing awareness to the risks involved with the state’s proposal, explore safer alternatives, and call on the state to disclose all conflicts of interests.

Rally participants are urging the public to comment on the Environmental Assessment before the upcoming Jan. 23 deadline.

“We have an opportunity now to let these agencies know that we do not consent to this research being conducted on Maui. The potential impacts to the ‘āina and to our health are significant. This plan is a dangerous experiment on the land, birds, wildlife, and people of these islands,” said Tina Lia.

According to the EA filed in December 2022, at least two endangered bird species in East Maui–the kiwikiu (Maui Parrotbill) and ʻākohekohe, are expected to become extinct within two to 15 years if avian malaria is left unchecked. The estimation was detailed in a study published in the scientific publication Journal of Field Ornithology.

The EA further states that there are currently fewer than 200 kiwikiu and fewer than 2,000 ʻākohekohe persisting in the wild, all of which are located within the project area. Both species have declined by more than 70% over the last two decades. Four additional Hawaiian honeycreepers also reside on East Maui: the threatened ʻiʻiwi, Maui ʻalauahio, Hawaiʻi ʻamakihi, and ʻapapane. These species are also affected by avian malaria and addressed in the EA.

According to the EA, this approach uses a naturally occurring bacteria called Wolbachia that is present in many insect species on Maui. “When male mosquitoes with an incompatible strain of Wolbachia are introduced to a population of female mosquitoes, mating is unproductive, thereby suppressing mosquito populations,” and in turn suppressing the transmission of avian malaria, according to the document.

Participants also spoke for the protection of Maui’s native birds, environment and public health, but say they want a more thorough study to explore the impacts of the project.

Rally co-coordinator Bruce Douglas said he is concerned that “the state is trying to get away with presenting a simple Environmental Assessment rather than doing a thorough Environmental Impact Statement, which would include a detailed analysis of the risks associated with this plan.”

The project area spans 64,666 acres of East Maui, covering Haleakalā National Park and extending from Makawao Forest to the Hāna and Kīpahulu Forest Reserves.

“We’re talking about possibly up to 775,992,000 mosquitoes introduced per week on this island alone, over 40 billion per year. There would be drones, helicopters, and people on foot releasing up to 12,000 mosquitoes per acre weekly,” said Lia. The permit application to import the mosquitoes, along with the EPA website, give an accidental release rate of one female for every 250,000 males, according to rally organizers. Lia said, “these accidental females can bite and breed, and may spread disease to humans, birds, and other species.”

Organizers also worry about the timeline for the project and the categorization by the EPA of the Wolbachia bacteria-infected mosquitoes as a bio pesticide.

“This state has a history of trying to solve one problem, then creating an even bigger problem by importing species like the mongoose,” said Bruce Douglas. “We don’t want this experiment to be unleashed on our island home. Once the first mosquito is released, the effects of this plan are irreversible, and potentially catastrophic. Who’s going to take responsibility if something goes wrong?”

_1768613517521.webp)