New Maui Hale Match website trying to connect fire displaced residents with affordable places to live

On Aug. 8, with her Lahaina neighborhood already on fire, Amanda Vierra grabbed her two boys, 4-year-old Isiah and 9-year-old Konner, and her two pets, Alohi the dog and Bagheera the cat, and escaped in her Jeep Cherokee that thankfully had 4-wheel drive to power over downed trees blocking the roads.

But trail-blazing her family to safety was just the beginning of an ordeal that has no end in sight.

On Oct. 23, two days before her 35th birthday, Vierra will have to move for the 7th time in 2 1/2 months — since the fire destroyed almost all her belongings in her rented 3-bedroom apartment behind the Pioneer Mill that burned to the ground.

Where her family will live next, she does not know. She mustered that this time moving would be easier because she got bins.

To help people like Vierra, Native Hawaiian Matt Jachowski has used his skills as a software developer to create the website Maui Hale Match, which he hopes will make it easier for displaced fire survivors to connect with homeowners and landlords that have available units they can afford.

Jachowski knows firsthand about the difficulty of making that match, but in his case it is from the property owner’s side. He and his wife had a 3-bedroom family home near Pāʻia Elementary School that they wanted to rent to a displaced family with keiki.

But finding the right family proved more difficult than expected.

“We wanted to get a family that was the right size that had kids around that age,” he said. “Even though we’re all community members, finding that right family was hard.”

Nicole Huguenin, co-director of the nonprofit Maui Rapid Response that is sponsoring the website as a project, said Jachowski’s housing app is desperately needed.

She said it’s like the dating app Match.com.

But instead of attempting to match soulmates, the housing website is designed to match displaced fire survivors with landlords or property owners offering the right size housing in the right location at the right price.

More than 8,000 people were displaced when more than 2,200 structures in Lahaina and another 19 structures in Kula were destroyed in the Aug. 8 fires, and from other homes made unlivable due to a lack of electric, water and wastewater. The majority still are living in temporary housing.

While just having any kind of roof over one’s head is the first step during the beginning of a disaster, as the days turn to weeks turn to months, displaced people and families are looking for and needing living situations that are more permanent and workable for their situations, especially families with young children.

On the Maui Hale Match website, displaced fire survivors input the type of housing they need, their situation and what they can afford. Property owners and landlords input what type of housing they can offer and any other pertinent information.

When there is a match, the person looking for the housing and person offering the housing are each notified about the other through email. Then it is up to the two sides to do the rest, hopefully resulting in a lease.

The site launched Oct. 7 and through Tuesday evening, it already has 499 registered housing requests representing 1,616 people in need of long-term housing. So far, 42 landlords or property owners have offered 112 housing units for rent.

There have been 30 connections in which both sides “opt in,” Jachowski said.

While he does not know if these connections have resulted in signed leases, he said: “I donʻt think these connections would have happened without the website.”

The state has attempted its own housing matchmaking.

While Hawaiʻi Gov. Josh Green announced it as the Hawai’i Fire Relief Housing Program, in reality it’s not much more than a place where landlords and property owners in Hawai’i can list available housing units that anyone can access. People looking for housing could also fill out a form.

But it was left up to displaced fire survivors to go through the long list and contact the landlords or property owners.

Gordon Y.K. Pang, housing information officer for the Hawaiʻi Housing Finance & Development Corporation that oversees the list, said last week there were no resources available to do more at the time.

“We just tried to put together something quickly,” he said.

The state started the listing six days after the Aug. 8 fires, when thousands of people were desperate for housing and the use of hotel rooms for housing through the American Red Cross had yet to get underway.

When the Hawai’i Fire Relief Housing Program was launched, a news release said it was designed “to connect those in urgent need of housing due to the Maui fires to Hawaiʻi homeowners willing to assist by offering unoccupied rooms, units or houses on a temporary basis.”

In the first four days, nearly 700 requests were made to house about 2,200 individuals. In the same time frame, owners and landlords made available more than 900 housing units across all four counties of the state, according to a state news release.

But like Jachowski found, matching people with housing that is affordable and in a location near the Lahaina schools or people’s work — for those who still had jobs — has proven to be difficult.

As of Oct. 17, there were still 600 housing units on the state program’s available housing inventory list, with only 124 located in West Maui.

According to state figures provided as of Oct. 11, the state program received offers of 1,357 units, but only 370 “are deemed filled or occupied.”

It also is not known that of those 370 units that were filled, how many were by displaced residents.

“While the hope is that priority is given to survivors of the fires, our listing is public and allows anyone to access it,” said Gordon Y.K. Pang, housing information officer for the Hawaiʻi Housing Finance & Development Corporation.

He added that the corporation is reaching out to other government agencies, including nonprofits such as the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement and the Hawaiʻi Community Foundation, on how best to increase the number of long-term housing opportunities to those displaced by the fires.

“Now that we have this platform for people to easily connect, the problem becomes convincing landlords to sign up,” Jachowski said. “I think we need to reach the second home owners and landlords who typically rent to affluent transplants from the mainland.”

But the biggest barrier now seems to be price.

Look at inventory, there is inventory on this island,” said Huguenin with Maui Rapid Response. “It is just not affordable inventory.”

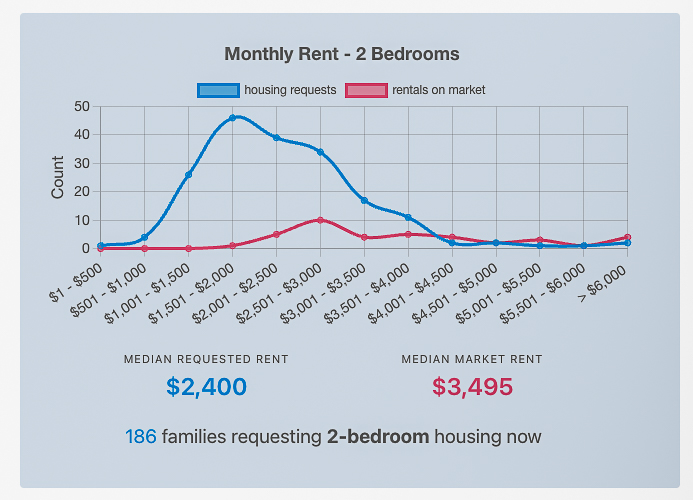

Jachowski’s analyzed the data he has collected on his website — with average unit costs based on active long-term rental listings on Craigslist, Trulia and Realtor.com, excluding “ridiculously high” rentals of more than $10,000 a month. It shows, as expected, that there is a large gap between the market rate of Maui rentals and the rent that displaced families say they can afford.

But how big a gap?

Jachowski’s data shows the median monthly rent for a 2-bedroom home on Maui right now is $3,495. But of the 186 families who registered on Maui Hale Match for a 2-bedroom home, the median rent they say they can pay is only $2,400 per month. That’s nearly $1,100 a month difference.

The gap is lower but still substantial for one-bedroom housing ($700), and higher for 3-bedroom units ($1,500) and 4-bedroom place ($1,400).

“Everyone has known that the rent was too expensive, but they didn’t know what the rental gap was for specifically for 1-bedrooms, 2-bedrooms, 3-bedrooms and 4-bedrooms,” Jachowski said.

Vierra received a match, but said it didn’t work out because she couldn’t afford it. Vierra lost her job as a cashier and teaching tourists to fish at West Maui Sporting Goods, which burned in the fire.

On the state’s available list, many of the units also are available for only three months or less, not the kind of stability people and families are looking for, especially people who have moved several times between shelters and hotels.

“I don’t have any money to fill that rental gap, but maybe the government does,” Jachowski said. “It’s going to help the government know how much money they need to fill the rental gap. Right now, all I can do is make an emotional appeal to the landlords and homeowners and say, you’re asking for too much.”

Sandi Loakimi is one such property owner who is willing to rent below market value to a family displaced by the fire.

“Iʻm moving into the cottage to make room for a family,” she said. “Other people give money. It’s all I have to give.”

She is doing a quick renovation of her main 3-bedroom, 2-bath, 1,600-square-foot house in Kīhei and renting it, beginning Dec. 1, for $3,500 a month, including utilities, WiFi and streaming services. It’s about $1,000 less than the average going rate for a 3-bedroom on Maui.

She also is accepting pets.

Finding the right place, which also accepts pets, has been a problem with the matchmaking. On Jachowski’s website as of Tuesday, 168 households looking for housing had pets, including seven households that had at least four animals.

Brandy Cajudoy said she used the new website to list a 300- to 350-square-foot studio in Kīhei with a shared kitchen for $1,100, which can accommodate up to two people.

“It is a good deal,” she said. “We tried to keep it reasonable.”

She said she contacted a couple of matches, but they didn’t want to fill out the applications.

“So I still have a place, but itʻs small,” she said.

Cajudoy said they also rented out one of their vacation rental to a displaced family of five through the Airbnb program with Maui Economic Opportunity, but the family didn’t want to stay past a month because “they really wanted to be back on the Lahaina side.

“I think that is part of the issue. People really want to be in Lahaina. I don’t blame them. That’s home for them. But I’m just going to keep offering.”

Most of the families requesting housing want to stay on Maui, but a small number are open to housing on Oʻahu, Kauaʻi, the Big Island, Lānaʻi and Molokaʻi. Maui Hale Match encourages homeowners from these other islands to sign up and see if they can help.

The market for affordable housing is only getting worse with the federal “Safe Harbor” program to house anyone affected by the fires ended Sept. 29, meaning only people who qualified for Red Cross or FEMA disaster assistance would continue to receive housing help.

People who qualified for housing assistance can continue to remain in hotels until “additional sheltering options are finalized.”

But others have been required to leave, which will only make the housing market tighter for affordable units.

For Vierra, she is hoping she can trade “cleaning properties” for break on rent with a property management company. So far, every time she is faced with having no place to live, something has come through. One time, two tourists gave her $300 when they saw her crying when she was down to the last day in her latest rental.

While Vierra would qualify for living in a hotel, she said with no kitchen, that is not a good situation for raising kids who eat all the time, even though they would receive three meals a day.

Her oldest boy lives with his dad in Kīhei so he can have a steady place to go to school. But he also stays with her, too, along with her boyfriend, the father of her youngest son.

“In a pinch, if we have to live in a hotel room, we will,” she said. “You do what you have to do to survive.”

_1768613517521.webp)