Hawai'i Journalism Initiative

Hawai'i Journalism InitiativeLahaina fire debris relocation to Central Maui 50% done, but traffic increases with schools back in session and high surf

Todd Hayase recently started his 32nd year working as a counselor at Lahaina Intermediate School, which he commutes to five days a week from his home in Pukalani 32 miles away.

While those drives to and from school to home have varied in time over the decades, since the start of school last week, Hayase said this year’s commute has “been the worst.”

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

He’s not the only one who thinks so. Trixy Nuesca-Ganer, the former Lahainaluna girls volleyball coach who has lived in seven places since the 2023 wildfires destroyed three generational homes, now lives in Kahului and also regularly makes the drive.

She said she left her home in Kahului at 8 a.m. on Thursday and it took 2 hours, 32 minutes to get to her new job in West Maui as a facilities manager with Alpha Inc. Hawaiʻi. On the commute home, she left at 1 p.m. and it took more than 90 minutes.

Hayase and Nuesca-Ganer believe the reasons for the traffic woes stems from a combination of factors, including king tides overflowing parts of Honoapiʻilani Highway, prime wave conditions drawing surfers, fire survivors commuting to Lahaina for work and school from different parts of the island, and the constant flow of trucks delivering fire debris from Olowalu to Central Maui.

The 50 trucks identified by “Lahaina Wildfire Debris” decals are making “several round trips” each day, according to the Maui Recovers website.

Hayase is certain it is not any one of the factors, but a combination of all of them that has led to the gridlock.

“It’s not (solely) because of the Lahaina debris trucks,” he said. “Don’t get me wrong, they stop traffic here and there.”

The gridlock used to be predictable in the morning and afternoon, but “now it’s just all day,” Nuesca-Ganer said. She said it’s not just the debris transport, but also the number of cars on the road, tourists stopping for the views, frustrated local drivers and the high surf and high tides encroaching on the roadway.

“Those are all things that work against us with having one way in and one way out,” Nuesca-Ganer said.

Hayase thinks the number one culprit is the 200 feet of flooding of Honoapiʻilani Highway near Ukuehame that he says is now happening regularly.

“I got to come home and shoot down my entire truck and underneath (with fresh water), because it’s getting pounded by salt water right there,” he said.

Nuesca-Ganer added: “Because of the high tide and the high surf, it didn’t matter what time you left, you were gonna get caught in the traffic no matter what.”

Those issues will be addressed in the state Department of Transportation’s $160.8 million project to move Honoapiʻilani Highway mauka. Pre-construction is set to start in the fall, but construction is not scheduled to begin until 2027 and the project’s completion date is not until 2030.

But the good news for commuters is that the relocation of the 400,000 tons of fire debris from the temporary site in Olowalu to the permanent site 19 miles away at the Central Maui Landfill is moving quicker than anticipated and already is more than halfway complete, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers who is leading the project and the mauirecovers.org dashboard.

This amount was estimated two years ago to be able to fill five football fields, five stories high.

Donald Schlack, the Army Corps chief of staff for the recovery mission on Maui, said the exact percentage that has been moved as of the end of last week was 53%.

The debris removal effort for the Army Corps began soon after the Lahaina wildfire on Aug. 8, 2023, destroyed more than 2,200 homes, complexes and commercial buildings in Lahaina and another 26 homes in Kula.

“We coordinated with the county and the state and the Lahaina community for many months before we started this operation of moving the debris,” Schlack said. “So we did a lot of coordination to identify what kind of issues there might be, what kind of challenges there could be.”

The Army Corps has pushed back the seven-days-a-week effort for the truckers to six days a week. Last Sunday was the first day off since the effort began in mid-June.

“After the first week or so, they were able to get into a routine which seems to be working for everybody,” Schlack said of the frequency of the temporary traffic light that allows the trucks onto their route to the Central Maui Landfill.

The Army Corps said it also has been coordinating with the Maui police and fire departments “to make sure that we were aware of their capabilities and their needs,” Schlack said.

The state Department of Transportation was also consulted “because we’re hauling along state routes. … So we worked in partnership with everybody to make sure that what we needed to do was gonna be acceptable to everybody and would work.”

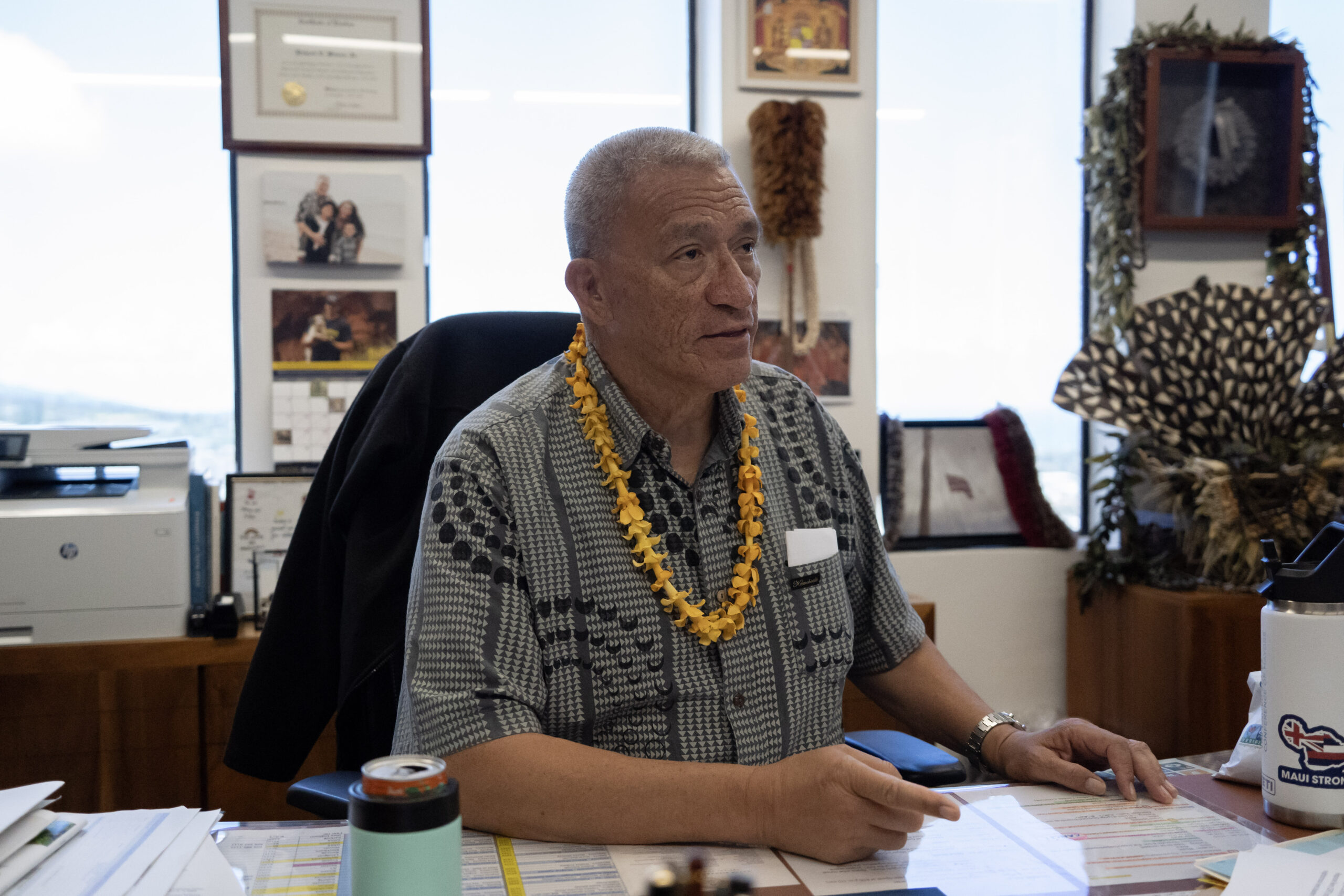

During the paddle-out event to commemorate the second anniversary of the fires in Lahaina and Kula on Aug. 8 at Hanakaʻōʻō Beach Park, Maui County Mayor Richard Bissen said that things are going well with the debris move.

Bissen said the cut back to six days per week will provide “some relief on the roads. We’re pretty happy at the pace that the Army Corps is working at right now.”

The original estimated date of the work to be done was November or December, but at the current pace of work it might happen more quickly.

“I think we’re averaging about 1% a day, as it turns out,” Bissen said. “And we had given ourselves until December to be completed. So, I mean, it’s looking pretty good.”

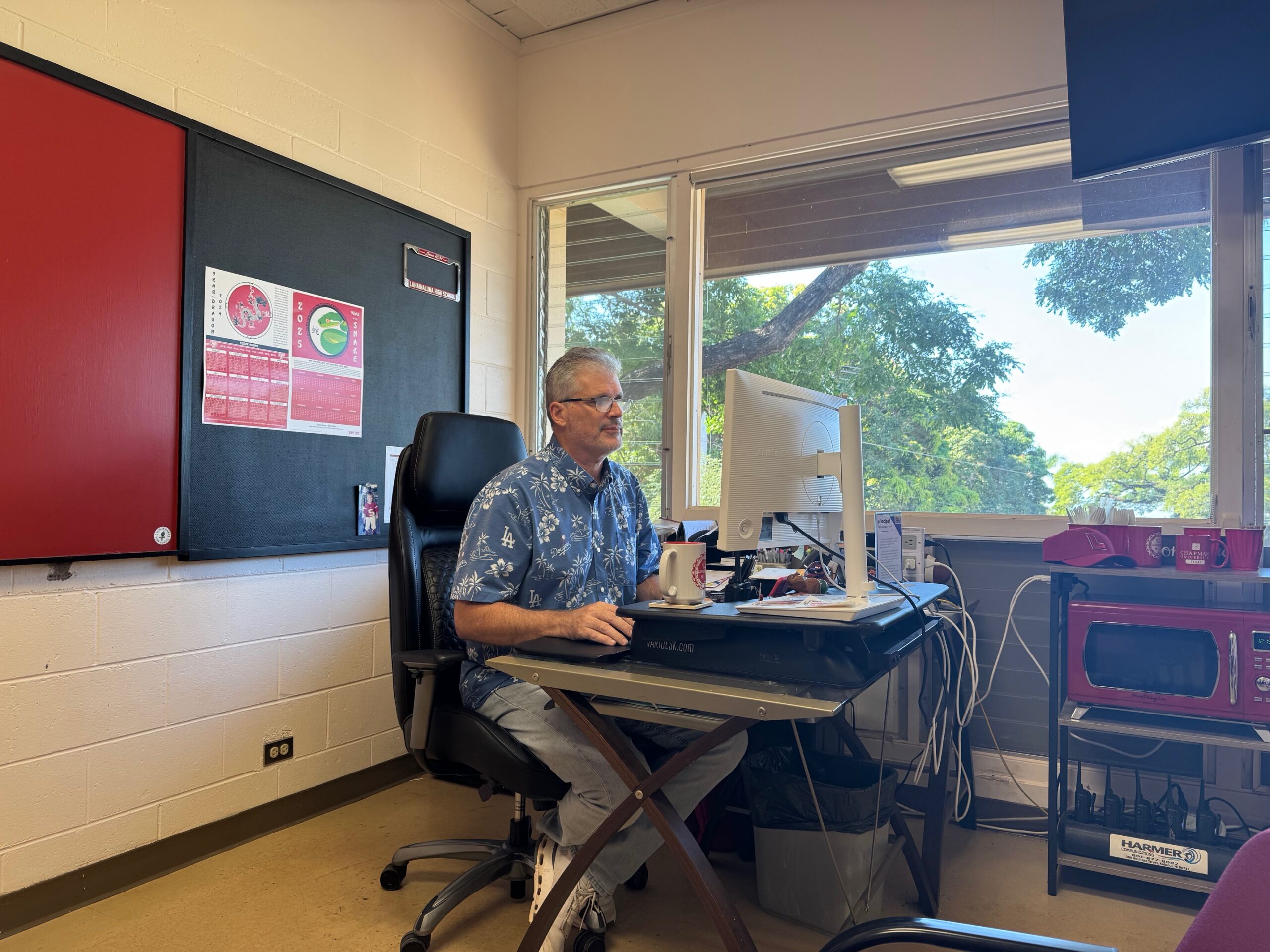

But until Lahaina is rebuilt, there will continue to be more traffic as students and staff commute to and from Lahaina schools during the school year. These long commutes have caused hardships for many teachers and students, said Lahainaluna High School principal Richard Carosso, who lives on campus most of the time but also has a house in Pukalani.

Carosso estimated that about half of his Lahainaluna staff commutes to West Maui and about 30 of the 827 students now attending the high school ride the county-run Maui Bus from Central Maui to Lahaina Cannery Mall in the morning and then catch a school bus to campus.

He said after school there is more student bus ridership because some students commute to school in the morning with their working parents. Going home, about 30 students take the city bus back to Kahului and then another 25 or so take the Department of Education bus that leaves later and goes to Māʻalaea and the War Memorial parking lot in Wailuku.

With so many of his staff forced to jump in their cars quickly after school to avoid the two-hour commutes that develop later in the afternoons, Carosso said it is affecting the school. With traffic at its worst in the early evening hours of 4 to 6 p.m., teachers are either racing to leave quickly after school or forced to wait until 7:30 p.m. or so.

“Otherwise, they’re sitting in traffic for hours,” Carosso said. “It hurts the school in the afternoons because teachers aren’t around to collaborate and to talk to each other.”

Carosso said his staff is willing to make the sacrifice of staying later and coming earlier to avoid snarled traffic on the Lahaina Bypass.

“It affects the school. These are great people,” Carosso said. “So we have not had a problem with people being on time in our first week of classes, but it takes a toll on them. And how long is this going to last?”

Nuesca-Ganer shakes her head when she thinks of the future. She lost her uncle David Nuesca Jr. in the fire and is afraid of the traffic jams on the one way in and out of Lahaina to Central Maui.

“We need to do something,” Nuesca-Ganer said. “People that are in Lahaina are sitting ducks again if another tragedy does hit.”