Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative

Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative‘We just have to start’: Nonprofit faces $40 million task of restoring 8 historic sites in Lahaina

Before the Aug. 8, 2023 wildfire in Lahaina, Theo Morrison made a habit of walking down Front Street, checking in on the shops, museums and harbor to see what was happening in town.

Now, her memories of Lahaina town and the work she did researching its history as executive director of the Lahaina Restoration Foundation will be integral during the nonprofit’s $40 million effort to restore eight historic sites damaged or destroyed in the fire.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

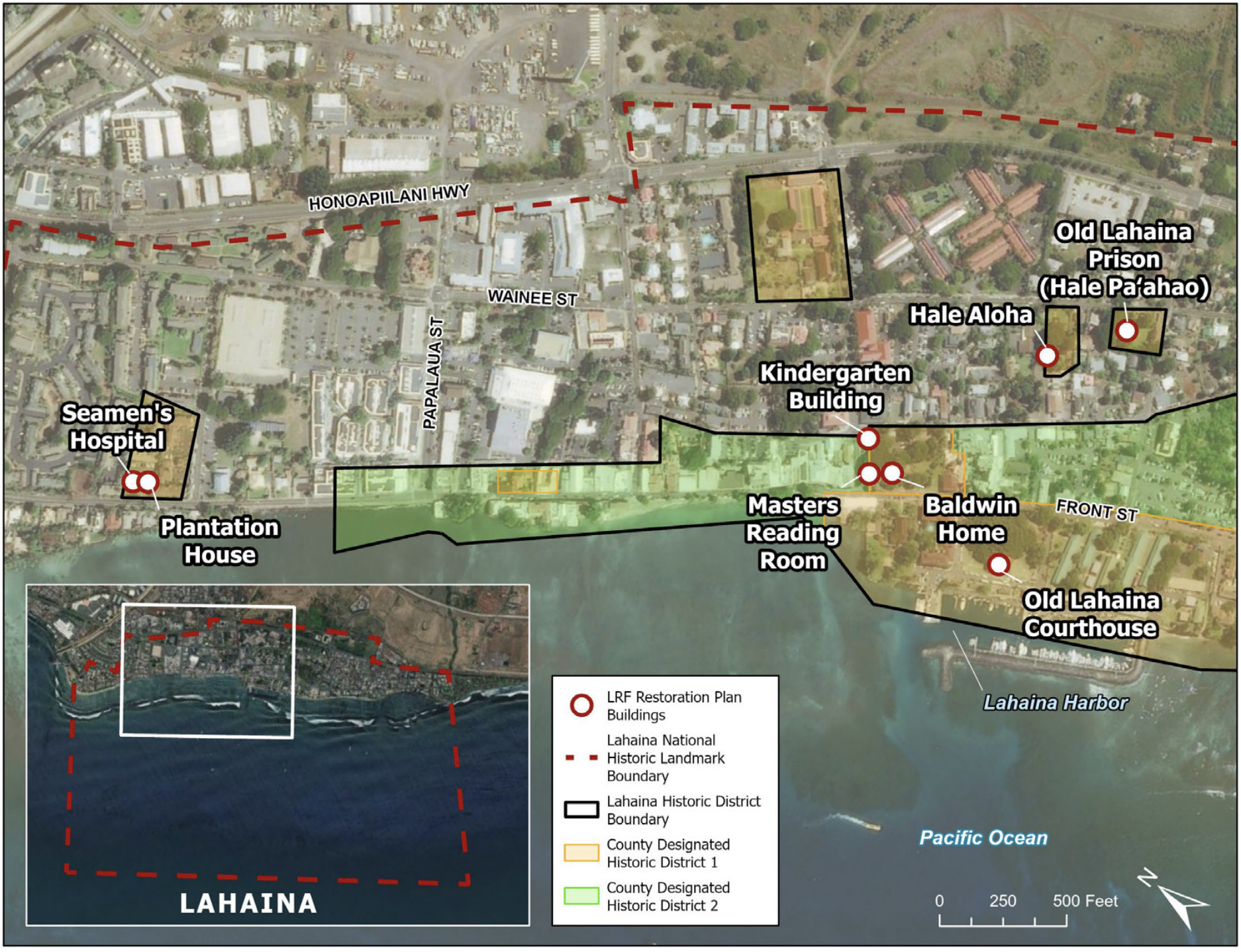

Last week, the foundation shared its master plan to restore the historic sites: the Old Lahaina Courthouse, the Seamen’s Hospital, the Baldwin House, the Masters’ Reading Room, Hale Aloha, Old Lahaina Prison/Hale Pa‘ahao, the Plantation House and the Kindergarten Building.

“The idea is to bring it back as much as possible,” Morrison told the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative. “We know it’s not totally possible, but as much as possible to what it was before.”

It’s a major challenge. The eight sites are in different physical conditions. With limited staff and resources, they can’t all be rebuilt at once. The foundation also is dealing with a donor pool of “strained Lahaina town supporters” who already were part of a massive outpouring of giving the past two years, the plan said.

The foundation plans to tackle the rebuilding in three phases:

- Phase I: Stabilization of the Baldwin Home, which was gutted by the fire but still has walls intact. That phase started in July of this year.

- Phase II: Studies, such as archaeological monitoring, topographic surveys and other work that needs to be done before the structures can be rebuilt. The goal is to get designs and permitting for most of the buildings and figure out an interim use for the Old Lahaina Prison site that still has open space and a portable toilet.

- Phase III: Construct Baldwin Home, Masters’ Reading Room and Kindergarten Building as one project or timed in close sequence. This would be followed by the construction of the courthouse, prison and Hale Aloha, in that order. Phase III would finish with the design and construction of the Seamen’s Hospital and Plantation House.

The Baldwin Home, which is located on the mauka side of Front Street across from the library and several shops, is expected to be the quickest to rebuild. The 2023 fire gutted the building and left only the stone masonry walls, which have been shored up with wooden beams and remain among the most standout landmarks on a street where nearly everything else was destroyed.

The Baldwin Home is the oldest remaining house on Maui. It was built by the Rev. Ephraim Spaulding around 1834 to 1835 to serve as a “missionary compound,” according to the master plan. The home was deeded to the foundation in 1961 and turned into a museum. Restoration is expected to cost $5.4 million and finish in 2028.

The 33,307-square-foot site where the Baldwin Home sits also includes the Masters’ Reading Room next door, which was built in the 1830s as a place for visiting mariners to read and families of ships’ officers to visit with the missionaries. The reading room’s stone walls are still standing and also had to be stabilized. It’s expected to cost $3 million to restore, with completion set for 2031.

The property also included the Kindergarten Building. It’s unclear when the building was constructed, but it was used as a school for years before it was conveyed to the foundation in 1961. It served as the foundation’s first office before becoming a retail art gallery. The fire completely destroyed the wood-frame building, and construction is expected to cost of $3.2 million and finish in 2031.

The most expensive of the buildings to restore is Hale Aloha, a 16,847-square-foot site slated to cost $7.5 million. The Waine‘e Church parish built the “House of Love” in 1855-58 to commemorate Rev. Dr. Dwight Baldwin’s vaccination and quarantine efforts that saved Maui from the smallpox epidemic. Over the years, it’s been used by the Lahaina Union School as well as the Waine‘e Church.

Maui County acquired it and partially restored it in 1973, and more restoration followed in the 1980s. Before the fire, the site served as a place for community gatherings, keiki camps, hands-on history, collections storage and curatorship.

The 2023 fire gutted the two-story building, destroyed the bell tower and restroom, and left only the concrete-block reinforced stone masonry walls. Construction on the site is expected to start in 2029 and finish in 2030.

The second-most expensive project is the restoration of the Old Lahaina Courthouse, which was gutted by the fire but still retains its plastered masonry walls.

Built around 1859 to 1860 and commissioned by the Hawaiian Kingdom, the courthouse served as a customs house for whaling and trade ships as well as a center for government offices and court functions, according to the master plan. It served as the town’s courthouse, jail, police station and other government functions until 1970. In 1988, it was leased to the foundation and renovated.

The 9,000-square-foot building, which includes a basement and two stories next to the famed banyan tree, is expected to cost $7.1 million to restore, with construction slated to start in 2028 and finish in 2029.

The plan envisions the rebuilt courthouse as a “revitalized hub for the community,” with uses including a museum on the history of Lahaina, a visitor center, a space for educational activities, event support, foundation offices and the Lahaina Arts Society Gallery in the former post office space on the first floor.

Costs and timelines for the other buildings are as follows:

- Old Lahaina Prison/Hale Pa‘ahao: $5 million, completion in 2030

- Seamen’s Hospital: $4.4 million, completion in 2032

- Plantation House, $1.7 million, completion in 2032

The foundation is eyeing a mix of funding to help drive the costly restoration, including Federal Emergency Management Agency funding, a Maui County grant, insurance payouts and the money they expect to get as part of the $4 billion settlement over the wildfires. Like most folks in the lawsuit, the foundation isn’t sure how much it will get, but Morrison said they have a “big claim” because so many of their buildings were impacted by the fire.

Five of the buildings were in public museum use prior to the fire — the courthouse, prison, Hale Aloha, Baldwin Home and Masters’ Reading Room — so they are eligible for FEMA public assistance funding. The foundation has to spend the money first, with the opportunity for the agency to cover 90% of rebuilding costs. The money has to be spent by August 2027, though that could be extended.

Another advantage for the courthouse, prison and Hale Aloha is that they were owned by Maui County, and the Office of Recovery has already set aside $1.8 million for the fiscal year 2026 to help start the design and permitting process.

The Seamen’s Hospital, Plantation House and Kindergarten building weren’t used in museums and thus aren’t eligible for FEMA funding. The hospital and Plantation House are listed as the lowest priorities in the plan because they will likely involve a longer fundraising campaign.

Morrison said the foundation has applied for a National Park Service grant of about $4 million that would help cover costs for the hospital, which was commissioned by King Kamehameha III in the 1830s and used as an inn before the U.S. government started leasing it in 1844 for sick and injured soldiers.

They’re also planning additional fundraising events, including their annual fundraiser with the Old Lāhainā Lūʻau in May.

The foundation plans to start seeking permits soon, but Morrison said the timelines in the master plan are best guesses depending on the challenges they face.

“We just have to start and then run into the issues as we run into the issues,” she said.

The privately funded, roughly $300,000 master plan, which was prepared by AECOM Technical Services and MASON, provides a clear direction and costs for the nonprofit moving forward.

“Getting that plan up was really great because now we know where we’re going,” Morrison said. “It’s very solid.”

She pointed out that most people from Lahaina want to see the town built back the way that it was, and for the historic buildings, that’s even more of an imperative. The plan is to keep the buildings’ historic facades and other key features.

Twelve years before the fire, the American Planning Association named Front Street one of 10 Great Streets of 2011, an award meant to honor places of exceptional character.

“It’s multimodal. It’s slow paced. It’s got great vistas,” Morrison said. “You got all the shops right there, the bikes and the cars just go together. … It’s like the epitome of what a great street is.”

But, she added: “What we’ve lost are the things that make a town a town, like the school, the library, the post office.” They were the kind of features “that regular people come to town to use.”

“Some things you can build back and some things you’ll never quite have the same as it was,” she acknowledged.

Last week, the county released design options for rebuilding Front Street that included plans to keep the roadway as two lanes. For both businesses and the Lahaina Restoration Foundation, the decision was critical in helping them move forward.

Morrison said if the county had decided to widen the road, the foundation would have had to make adjustments such as cutting down the stone wall in front of the Baldwin Home, and “there’s all kinds of problems with that.”

Businesses and historic buildings took the longest to clear of debris after the fire, and historic sites were especially a challenge because crews were trying to save what they could of the aging buildings. Six historic structures were shored up and braced during the cleanup of commercial and public properties, according to the recovery dashboard.

Morrison, who relocated to Wailuku after the foundation’s offices were destroyed and the neighborhood around her still-standing home was burned, is just excited to finally get started on planning for the rebuild of the historic sites. She said she feels like the county is “doing the best they can,” to move the rebuilding process forward, “but you gotta realize it’s like all new territory for everybody.”

“I’ve never been in this kind of tragedy before, so … I don’t know what’s normal.”