Hawai'i Journalism Initiative

Hawai'i Journalism InitiativeSpiking immigration arrests in Hawaiʻi over past year of Trump’s crackdown causing fear, backlogged cases, challenges for attorneys

Maui immigration attorney Kevin Block doesn’t usually handle cases for migrants in custody because of the required travel to the federal detention center on O‘ahu.

But over the past year, as arrests spike under President Donald Trump’s push for mass deportations, he and other lawyers have started taking them again.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

“We just all feel a responsibility to help,” Block told the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative on Monday.

Block and other Hawai‘i immigration attorneys have spent the first year of Trump’s second term juggling an increase in clients and a shifting legal landscape that they say is stoking fear in the community and making it increasingly difficult for immigrants, even those with legal status, in a state where nearly one-fifth of the population is foreign-born.

From January to July of this year, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrested 149 people in Hawai‘i, advocates with the University of Hawai‘i’s Refugee and Immigration Law Clinic told the state Senate Judiciary Committee on Monday, citing data from the Deportation Data Project. That’s more than triple the amount of people arrested during the same period in 2024.

On Maui, those caught up in the recent crackdown have included undocumented immigrants, people with legal status and U.S. citizens.

In May, more than 10 Maui County public school teachers were detained during an early morning raid on a Kahului home as agents sought a man who hadn’t lived there for over a year, the Hawai‘i State Teachers Association said. One of the teachers was a U.S. citizen; the others were from the Philippines and were in Hawai‘i on J1 visas as part of a cultural exchange program.

In August, a Lahaina fire survivor who lost his home and business was arrested by federal agents on the two-year anniversary of the 2023 blaze. Loved ones said in a GoFundMe page that he had first come to the U.S. as a minor and lived in Hawai‘i for 20 years, with no criminal record.

In October, an undocumented Maui man was detained by federal immigration officers at the Wailuku Courthouse as he went to a court hearing for driving under the influence and driving without a license. The Hawai‘i Department of Law Enforcement called the arrest in a state facility an “overstep” and said that staff had been directed to not assist ICE agents.

Across the islands, mass arrests have taken place in Kaua‘i neighborhoods and Kona coffee farms.

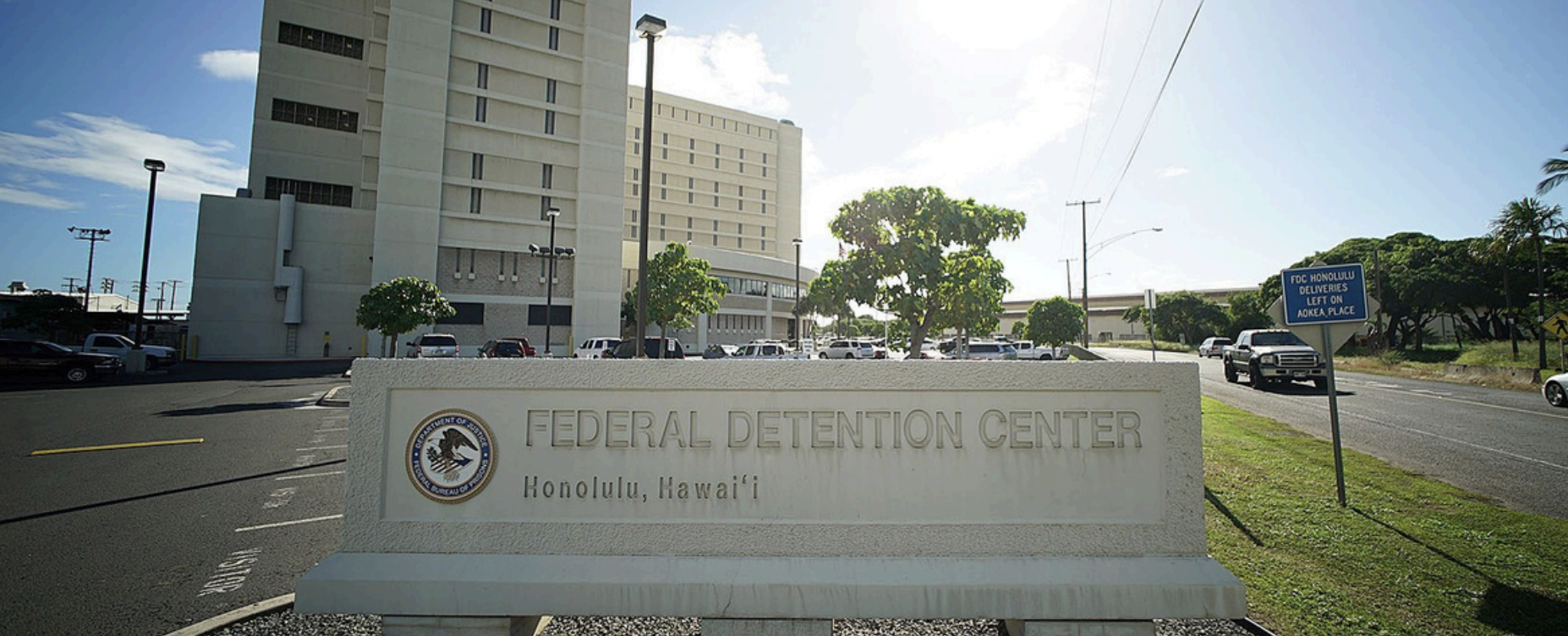

On any given day, anywhere from 40 to 80 people are being held at the federal detention center in Honolulu, where they are housed alongside people convicted of crimes and are subject to requirements like full-body cavity searches, said Pilar Kam and Stephanie Haro Sevilla, postgraduate law fellows with the Refugee and Immigration Law Clinic.

And while the Trump administration says it is pursuing the “worst of the worst” criminals, 67% of those detained by ICE at the Honolulu detention center have no criminal history, according to Bettina Mok, executive director of The Legal Clinic.

Kam said the enforcement has shifted from people who were convicted of serious crimes to now include those who were going through the legal channels and previously didn’t have to fear detention as much.

“But that framework is completely gone,” Kam said. “In its place now, we have a strategy that has a much wider web.”

As it tries to detain more people, the federal government is striking agreements with local police to give them the power to carry out arrests or other federal immigration enforcement, explained Liza Ryan Gill, co-coordinator of the Hawai‘i Coalition for Immigrant Rights.

Before, “these agreements were not very attractive to local law enforcement” because they didn’t want to do the feds’ job for them, Gill said. But now with much more funding on the line for agencies who participate, over 1,220 agreements have been signed across 40 states. Hawai‘i is not listed among them, though the Maui, Honolulu and Kaua‘i police departments do have agreements with Homeland Security Investigations, which is part of the Department of Homeland Security along with ICE, Honolulu Civil Beat reported in April.

Kam, Mok and Gill were among the legal experts and advocates who spoke to the Judiciary Committee as part of a hearing on immigration enforcement across Hawai‘i. The state is home to 92,800 non-citizen residents and 62,495 legal permanent residents eligible to apply for citizenship.

Mok said the increase in arrests is putting more pressure on what’s already “a broken system.”

Hawai‘i has a backlog of 1,400 immigration court cases, over eight times the number of cases in 2022. Nationwide, there’s a backlog of 3.4 million cases in immigration court and 11.3 million U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service applications, which include requests for citizenship and green cards and renewals of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program that grants legal status to people who were brought to the United States as minors.

“In the United States, it should not be a party-line-fracturing matter because it affects everybody,” Mok said. “Even presidents before this one struggled with this complex issue, and we know that the immigration system in the U.S. is broken.”

Hawai‘i has one of the best rates of representation for immigration cases in the country, according to the American Immigration Council and Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC).

But not everyone can afford a lawyer, especially when private attorneys can easily charge $10,000 to defend an asylum case because they are time-consuming and require specific expertise, Mok said.

In federal immigration court, there are no public defenders like there are in state court for those who can’t afford an attorney. Hawai‘i has 12 attorneys among the six or seven nonprofits that provide immigration legal services for low-income residents, and Mok said only eight of them can take removal defense cases. Most of these positions are not funded beyond a year.

That puts immigrants who can’t get or afford an attorney at a disadvantage, as studies have shown that those with legal representation are more likely to obtain relief, Mok said.

Haro Sevilla said that the law clinic received no calls from individuals at the federal detention center in 2023 and 2024. But as calls rose in January, they set up a dedicated hotline that can be reached by call or text at (808) 204-5951 from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. It’s drawn over 200 calls.

The few attorneys who offer low-cost or pro bono immigration services “often experience burnout, secondary trauma and have no choice but to turn away individuals with dire legal needs for immigration because they are at max capacity or over capacity,” Haro Sevilla said.

And, because of how fast arrests and deportations are moving “and how limited they have access to attorneys, many individuals don’t know that their due process rights are being violated,” she said. Before, attorneys used to be able to go to the detention center as soon as they got the name of an individual. Now it takes several days to get approval, which is critical because detainees are often taken to court before then.

Block, the founder of Maui Immigration Law, saw his own case load increase in the first six months of the year. The trend was expected — under administrations that are “hostile” to immigration, folks with pending cases try to advance their status as much as they can, he explained.

On Maui, the migrant community is seeing the cumulative effects of Trump’s first and second terms, the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and the 2023 Maui wildfires, Block said. People are more scared to participate in civic life and worried about seeking public assistance even after losing their homes or businesses. During the pandemic, one of his clients asked if it was safe to accept a box of food given out by her church.

“I would say that (after) COVID and the fire … the hardest thing for me to watch was just knowing that people were suffering and needing things, but that they didn’t feel safe to access them,” Block said.

Immigrants who are detained on Maui are taken to the federal detention center on O‘ahu, which makes it difficult for attorneys to visit their clients because they have to travel off island and never know when the facility will be on lockdown as it was at times during the recent government shutdown, Block said.

It’s also challenging for family members to visit, and they likely won’t risk it if they’re worried about their own legal status.

Changing policies also are making it more complicated for immigration attorneys and their clients, Block said.

For example, people with asylum claims who have succeeded in proving they could be in danger if they returned to their country of origin are now having to prove they would also face harm if sent to a third-party country, a tactic the U.S. has been using and that the Supreme Court paved the way for earlier this year.

Block said shifting policies have created confusion for attorneys, judges and the immigration agents he has communicated with over the years.

Every two weeks, Block participates in a virtual nationwide briefing, which helps him stay on top of what’s happening. Locally, he said attorneys and local agencies are divvying up the labor — the lawyers keep working the cases on the front lines, while the advocates track the policy changes that could impact people in Hawai‘i.

With ICE’s annual budget being tripled and resources being reallocated from other agencies to immigration enforcement, local advocates expect more challenges on the horizon.

“What we’re seeing today in terms of the arrests and the detentions and the removals is just the beginning,” Kam said. “And what we fear is that this is going to start affecting folks who are lawful permanent residents.”

Gill said there’s nothing that state or county authorities can do to stop agents with a valid judicial warrant, which is needed to enter someone’s private home or business. However, she said, oftentimes they do not have those types of warrants that are signed by a judge, “and they are relying on the fact that people will just do what they ask them to.”

Gill said the state has the opportunity to provide additional protocol in places where it wields authority or invests funding, “whether that is in our courts or our local schools, some of our hospital systems, to be able to say in these places, we are just going to make sure that you are doing things the way that has been prescribed.”

As state lawmakers prepare for the upcoming session next month, Gill said she hoped to see measures like House Bill 440 return. The bill would bar certain educational agencies and health facilities from collecting data on immigration status or allowing immigration agents to enter except under specific circumstances.

Gill’s organization and others are also promoting bills that have advanced in other places, such as measures to ensure that federal agents identify themselves and not wear masks as well as measures to standardize the visa process for victims of trafficking or other crimes who have been helpful in investigations.

“I don’t want folks to feel that we are hopeless or helpless,” Gill said. “There are things that we can do, even though it is more limited than we would prefer.”