Hawai'i Journalism Initiative

Hawai'i Journalism InitiativeKaho‘olawe Nine protest helped spark rebirth of sacred island 50 years ago today

Exactly 50 years ago today, a flotilla of 10 boats with about 60 people left Maui on a risky, seven-mile quest to cross the ʻAlalākeiki Channel to protest the sacred island of Kahoʻolawe being used by the U.S. military as a bombing range.

With military helicopters overhead and U.S. Coast Guard vessels in pursuit, just one boat made it to the island that had been off limits to civilians.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

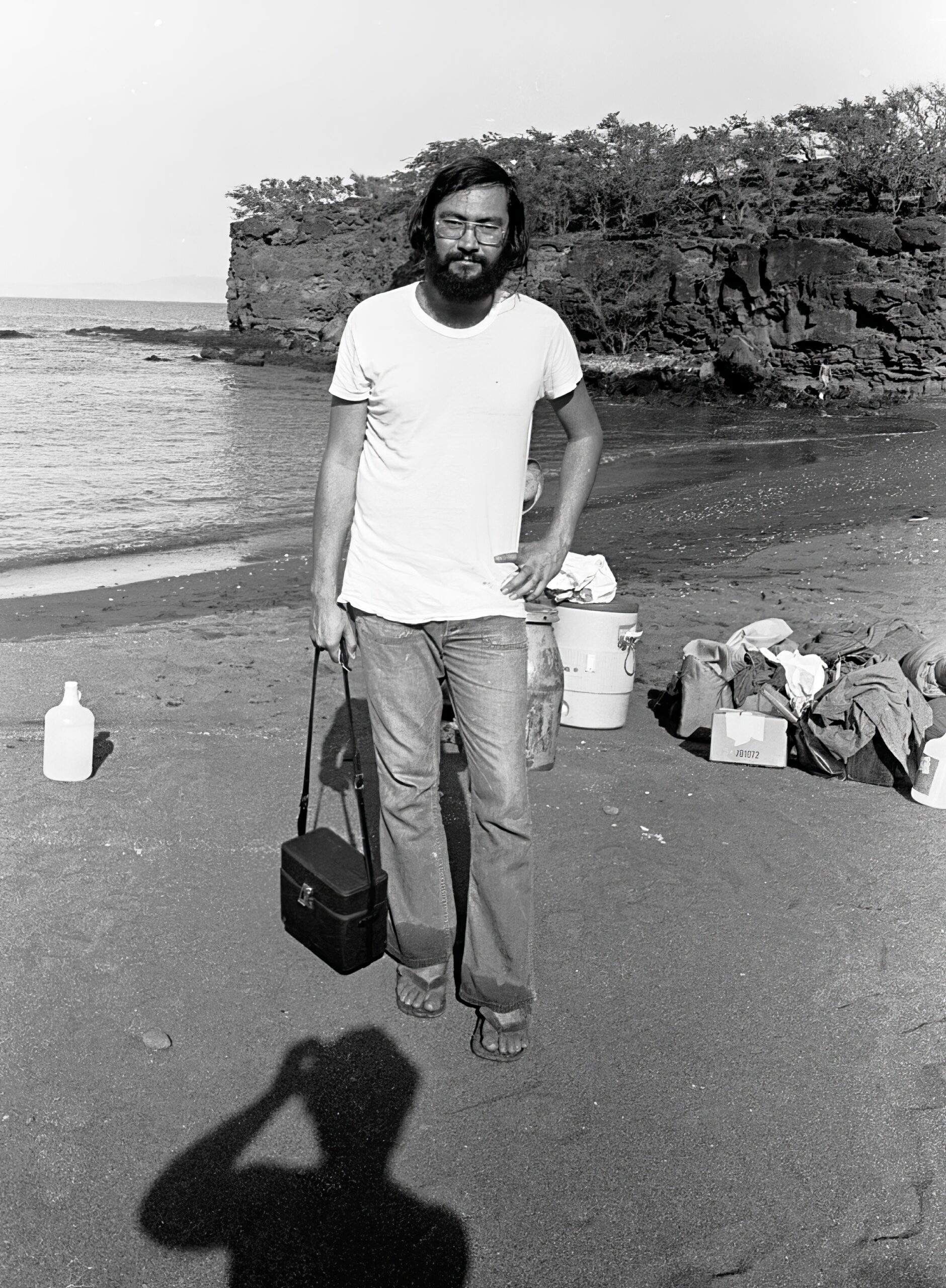

The diverse group of people aboard the boat that made it to shore became known as the Kahoʻolawe Nine: George Helm, Dr. Noa Emmett Aluli, Kimo Aluli, Kawaipuna Prejean, Walter Ritte, Ian Lind, Ellen Miles, Steve Morse and Karla Villalba. The boat captain was David Padgett.

On the other side of the channel aptly named ʻAlalākeiki, which means “crying child” in the Hawaiian language, the group saw trees uprooted, archaeological sites destroyed, and massive holes hollowed out of the earth. Unexploded ordnance was scattered across the land, and shrapnel fragments disintegrating into the soil.

“The first thing that got to me was the fact that they were actually using our historic sites as targets,” Ritte said. “There were white paint circles and X’s, and they were using our sites as targets.

“So, the first thing that hit me was anger. Because they were destroying our ability to learn about our ancestors, because we never had a written language.”

The anger turned into action. It took persistence, and cost the lives of two people, but on Oct. 22, 1990, the bombing and military use of the island finally ended. On May 7, 1994, the island officially was turned over to the State of Hawai‘i, and Congress appropriated $400 million for a 10-year project to start the clean up the island and the unexploded ordance.

The restoration of the sacred island, and the crusade for Native Hawaiian rights, continues today with the next generations inspired by the Kaho’olawe Nine.

Today, two events will honor the landing of Jan. 4, 1976.

The Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana will hold a press conference and celebration at 10 a.m. today at the Bailey House Museum in Wailuku. The organization was formed shortly after the landing “because people then realized how important the island was, and that we needed to organize to protect the island.”

The organization now has about 50 to 60 active members and 150 overall. It manages about 600 cultural sites, said member Davianna McGregor, who was the life partner of the late Dr. Aluli.

The Kaho‘olawe Nine were determined to draw national attention to the illegal role the U.S. played in the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi and to protest U.S. military control and destruction of Hawaiian national lands, Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana said in a news release about the event.

“Their courage and heroism in risking not only arrest, but death was the catalyst for the formation of the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana and the birth of the modern Aloha ‘Āina Movement that now celebrates 50 years.”

Ritte, who has lived a life devoted to political activism since that day 50 years ago, will hold an event at Hawaiian Brians on O‘ahu at 4 p.m. today.

He wrote on his Facebook page: “50 years ago we invaded Kaho ‘olawe and stopped the military bombing, tomorrow Jan 4th at 4:00pm we celebrate and organize to deal with new military use of our lands.”

Ritte’s event will feature a video by Kalamaku Crabbe about Kaho‘olawe and music by Olomana, Raiatea Helm, Ledward Ka‘apana, Vitals and Kealamaoloa. There also will be speakers discussing military use of lands, including former Hawai’i Gov. John Waihe‘e III, professor of Hawaiian studies Jon Osorio, Kaho‘okahi Kanuha and Aundre Perez representing Mauna Kea, and Noe Goodyear Ka‘opua of Kamehameha Schools.

Lind, now 80 years old, said he believes only four of the Kaho‘olawe Nine are still alive. They include Ritte, Kimo Aluli and Villalba.

Lind, reached by phone Wednesday at his home in Honolulu, said he has never been back to the island since that fateful day.

“I always said, at first, ‘I’m not going to go back under Navy auspices.’ And since then, it just hasn’t happened.”

Going to the so-called “forbidden island” was the idea of Hawaiian activist Charles Kauluwehi Maxwell Sr., who saw the opportunity to make a statement for Hawaiian rights in the turbulent era of the 1970s. It was a time when protests included the American Indian occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay from November 1969 to June 1971 and the 71-day-long Native American uprising at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

After the landing on Kaho‘olawe, the Coast Guard arrived and began rounding up the group. Ritte and Dr. Aluli, who would later begin a 46-year practice at the Molokaʻi Family Health Center, headed for the bushes to occupy the island.

“We spent, I think it was three days, Emmett and I, on the first landing,” Ritte said.

Dr. Aluli said before he died on Nov. 30, 2022, at age 78: “When you hear (the bombs), it’s … into your chest. I mean it hurts. Why are you doing this to the island? And people take it seriously, like it’s doing it to me. So it was the most devastating damage you will ever see. It hurt us.”

He added: “One of the old sayings is: ‘Take care of the land and the land takes care of you.’ The health of the land, is the health of our people, and actually the health of our nation. So we made a commitment to do something about it. And we were able to get the bombing stopped.”

But halting the bombing for good wasn’t easy and took years. The restoration also has been a long process that has required perseverance.

Protecting the island began with Helm, a Hawaiian rights activist and musician. Under the guidance of Aunty Emma Defries, Kahuna Sam Lono, Aunty Edith Kanakaʻole, Molokaʻi kūpuna and many others, Helm negotiated with the Navy to gain legal access to the island for a spiritual ceremony on Feb. 13, 1976.

The ceremony was to “ask permission of the island to come and help protect it, and also to clean … you have to clean the hewa (error, offense) from the military,” McGregor said. “And then you can connect with the ancestors to ask permission to be part of this effort for the island.”

Following the ceremony, the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana began organizing a grassroots Aloha ʻĀina movement throughout Hawaiʻi, gaining widespread support. The ʻOhana is spiritually guided by the Edith Kanakaʻole Foundation.

But the bombing did not stop. So neither did the protests.

In March of 1977, Helm and fisherman and park ranger Kimo Mitchell Kimo Mitchell were lost in the ocean off the island during their efforts to safely bring back to Maui two members of the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana who were occupying the island. Their bodies were never found.

Lind, who became a reporter at the Star-Bulletin newspaper in Honolulu from 1993 to 2001 and later worked as a freelance journalist, said few people realized the significance of Kahoʻolawe in galvanizing a movement before that first protest in 1976.

“I don’t think anyone foresaw that Kahoʻolawe itself would emerge from all that as the centerpiece (of the Hawaiian rights movement),” Lind said.

Since it was turned over to the state, the island has undergone a decadeslong rehabilitation effort that includes removal of some unexploded ordnance and planting of native species by staff and volunteers who are authorized to visit the island. McGregor estimates that more than 50,000 people have visited Kahoʻolawe, which now stands as a beacon of Hawaiian cultural, spiritual and subsistence purposes.

All visitors have to acquire official permission through authorized cultural, restoration or educational volunteer programs run by the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission. The island is not open to tourism due to hazards from unexploded ordnance and its sacred status.

The commission was created by the State Legislature in 1993 at the request of the Navy to help the clean up efforts of the bombing and unexploded ordnance for the next 10 years with money appropriated by Congress.

“What the Navy didn’t want to do at the time was to have to deal with … all these other (state) agencies,” said Mike Nahoopii, the commission’s executive director. “Imagine if you had to do the first (unexploded ordnance) cleanup ever in the United States and you’re dealing with seven different state agencies.”

Nahoopii recently hired a natural resource specialist for his staff of 14.

The commission has seven commissioners — three from the Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana, one from the Native Hawaiian Organization, one from the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, one selected by the Maui County Mayor and the chair of the state Department of Land and Natural Resources.

“We can blend both the past and the future together, science and culture process together, create a hybrid method of restoring our ‘āina and I think that for us it’s more of a process than the end results,” Nahoopii said. “For us, it is the journey of working with people who want to help the island.”

Fifty years later, the desire to protect and restore Kahoʻolawe remains strong.

Paul Ka‘uhane Lu‘uwai, the Hawaiian Canoe Club keiki coach for more than 40 years, has taken about 1,700 young paddlers to Kaho‘olawe over the past 35 years, including crew mates Mikaela Benavides and Keala Rodriguez, both 17.

Benavides, now a senior at Kamehameha Schools Maui, went to the island for the first time in 2022 with the Hawaiian Canoe Club as a 14-year-old.

“It really changed my perspective on my Hawaiian identity and what it means to be Hawaiian for me,” she said.

Rodriguez, a senior at Seabury Hall, said her grandfather has told her about living in Lahaina and feeling the shaking from the bombing of Kaho‘olawe when he was a child. Rodriguez plans to study environmental science or biology because of her experiences on Kaho‘olawe.

“Just recognizing everything that you have to see there and contributing to giving back to the land after it’s been bombed for so long, that’s important,” Rodriguez said. “There’s definitely some Hawaiian cultural values, like malama ‘āina or laulima that I have learned from going there.”

Like many others, Lu‘uwai used to go to Kaho‘olawe as a child on his father Bobby Lu‘uwai’s fishing boat despite the military bombing of the island.

“Until you’ve gone there you just don’t know what the island can offer and the mana and all the feelings of Kaho’olawe that really projects towards your body and your soul,” Lu‘uwai said. “Most kids that go who are trained properly, they are all touched deeply by the island.”

Rodriguez said the work the Hawaiian Canoe Club keiki do for the island is especially fulfilling. On their trips in recent years they have been working in an alaloa (main public pathway) or around the island trail.

McGregor said there are now approximately 25 miles of trails lined by rocks to keep visitors from wandering onto sacred land where Hawaiian kūpuna have left their mark.

“I feel like all of the work you do there really helps you reflect,” Rodriguez said.

It’s a full circle moment for Lu‘uwai, who was a student in McGregor’s Hawaiian ethnic studies class at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa in the early 1980s. He helped her get to the island for the first time via his dad’s fishing boat. She remembers the precise date: “November 19, 1983. I had tried three prior times, but my rides all fell through. Ka‘uhane made sure I got there.”

McGregor sees the work that Lu‘uwai does with his young paddlers and smiles because it is essential to carrying on the 50-year tradition of restoring and learning from Kaho‘olawe.

“Oh, we just love them. They bring a lot of energy, they bring a lot of inspiration and they’re very open to learning,” McGregor said of the young paddlers and their work on the island. “They learn to do what’s best for the island, which is so important because people on Maui need to know that Kaho‘olawe is an important place. It’s spiritually and culturally important.”