Hawai'i Journalism Initiative

Hawai'i Journalism InitiativeRestoring sand dunes could save Maui’s north shore, one of Hawaiʻi’s most eroded coastlines

PĀ‘IA — On the patch of sand where Baldwin Beach Park’s pavilion collapsed onto the eroding shoreline in 2024, Maui coastal hazards expert Tara Owens points out the native plants clinging to the windblown landscape.

The ‘aki‘aki, a coastal grass, and pōhuehue, also known as beach morning glory, were planted where the pavilion once stood. The goal: restore the sand dunes and keep the ocean from swallowing the beach, which is along one of the most eroded coastlines in the state.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

“This plant is like our workhorse,” Owens said of the pōhuehue’s cup-shaped leaves. “When the sand blows, the cup catches the sand … and then that’s what starts the dune.”

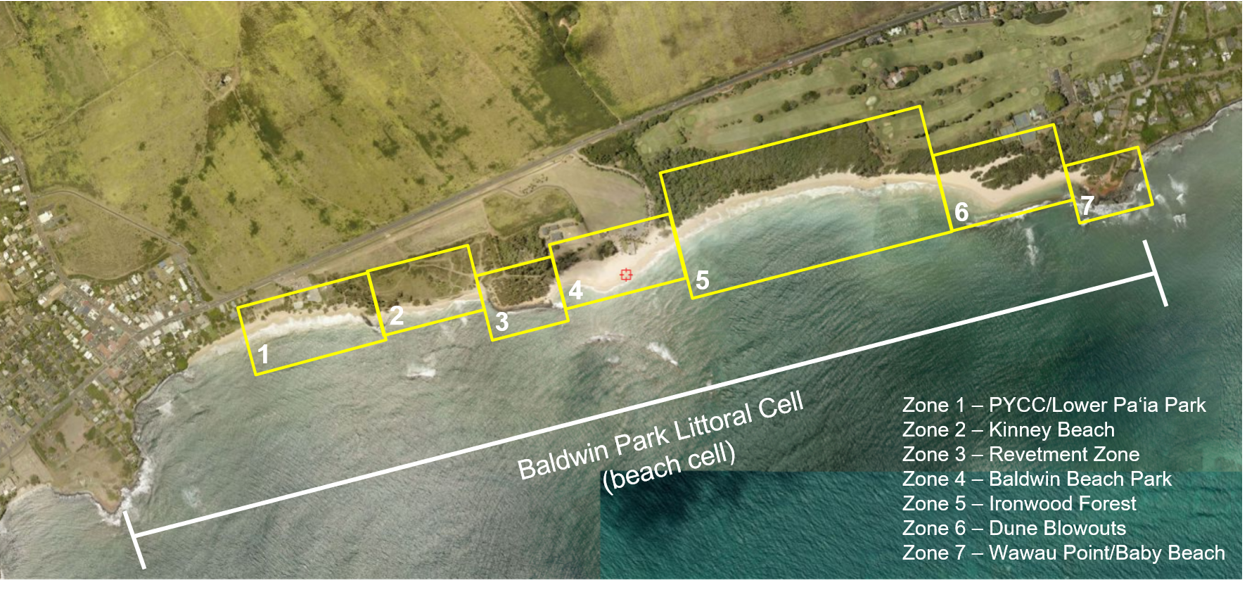

Owens and her team at the University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant program are spearheading an effort to restore the sand dunes along a 1.5-mile stretch of coastline from Wawau Point (Baby Beach) to Lower Pā‘ia Park. This area has been worn down by decades of sand mining, sea level rise and the relentless wind and waves of the north shore.

Recently, Maui County approved the permits needed to move the restoration project forward, and Sea Grant hopes to start work within the next year.

“We know how to manage the dunes, and we’ve been working at it a couple of decades now,” said Owens, Sea Grant’s Maui Nui program coordinator. “But it’s an underutilized tool still that we could do more of all around the island.”

During a community meeting about the project on Monday at Lower Pā‘ia Park, Owens explained that sand dunes are a critical feature of a healthy beach, stockpiling sand into elevated banks and releasing it as needed during big wave events.

From the early 1900s to the 1970s, large quantities of sand were mined from the area for use in concrete production and in the nearby lime kiln, built in 1907, to produce soil enhancements for the island’s sugarcane fields.

About 12,000 cubic yards of sand went to lime manufacturing, road surfacing and concrete each year, according to a 1954 report. That “extractive history” is the primary reason the area has eroded so much, Owens said.

“A beach has a sand budget, just like a bank account, and so if you’re removing sand grains, like dollars from the budget, you deplete your resource, and then that leads to higher erosion rates,” she explained.

While the sand mining stopped long ago, sea level rise now is taking its toll, pushing the shoreline back even farther and forcing oceanfront facilities like the Pā‘ia Youth & Cultural Center to prepare to relocate inland.

In 2018, Sea Grant received a $199,506 grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to prepare plans for a dune restoration project in the area known as Kapukaulua. In 2023, Sea Grant got a second round of funding of about $1.4 million to carry out the project.

Sea Grant finally secured a flood development permit for the permit on Oct. 7 and a special management area permit and shoreline setback approval from Maui County on Jan. 20.

Because the grant has one year left, Owens said the goal is to do the work within that timeframe, “but this is just the start of hopefully a decadeslong effort” to maintain the dunes and restore the beaches.

Sea Grant is leading the project in collaboration with Maui County and with support from the nonprofit Surfrider Foundation, along with guidance and support from many other community groups and people, Owens said.

The project area will be divided into seven zones. Each will require a different strategy of sand replenishment and native species planting, but the overall approach is the “three p’s”: plants that can withstand the waves, paths for public access, and perimeters to keep the planting areas fenced off so the dunes can grow back.

The plants ideal for building back the sand dunes are low-growing vines and grasses that can handle the salinity and the sun, and can “dig their way out” after constant inundation by the sand and the sea, said Jenna Spellman, leader of the Maui County Parks and Recreation Department’s “dune crew,” a three-person team that helps maintain shoreline restoration projects.

Figuring out where to plant requires a bit of trial and error. After the pavilion at Baldwin Beach Park collapsed and was removed in September 2024, plants were installed in October 2024. But the ocean came in and washed some sections away, forcing adjustments to the planting.

“I call it corrections. The ocean just lets us know,” Spellman said.

About 50% of what was initially planted was lost, “and we had some expectations of that,” Owens said. But the remaining plants have thrived, with some sand accumulation. Big swells still get through, but the waves tend to go around the steadily growing dune, she said.

Earlier this month, the county removed 18 coconut trees that succumbed to years of saltwater exposure from the waves washing up over the parking lot and beach. Eventually, the goal is to relocate the asphalt parking lot inland, and tear up the old asphalt to create a dune, Spellman and Owens said.

The model of success for the rest of the shoreline is the dunes at Lower Pā‘ia Park overlooking Pā‘ia Bay. When Benjamin Rachunas started working as the managing director of the nearby Pā‘ia Youth & Cultural Center in 2005, he used to see families crowd the park for barbecues and birthday parties.

Over time, winter waves began washing up over the park, covering the basketball court in debris, clogging the drain that Pā‘ia town needs during heavy rains, and turning the area into a “stagnant pond of swamp water” that discouraged family gatherings.

Rachunas and others at the youth center contacted the county and Sea Grant for solutions. In 2013, they started planting and putting in irrigation, fence posts and ropes. He remembers one 14-year-old girl from the youth center who helped plant a patch of ‘aki‘aki grass that has now gained about 4 feet of elevation as the sand accumulated over time.

“It literally just took a single shovel and someone who cared,” Rachunas said.

Restoring sand dunes along the rest of the shoreline will also require the removal of invasive species, including some dead ironwood trees that pose a safety risk and hold back the natural flow of sand, said Erin Derrington, founder and CEO of project consultant Eco Management and Design Services. She said there are potentially 80 trees closest to the shoreline that could be removed during the process, but it will depend on the budget.

While some residents said the area couldn’t afford to lose more shade, others said it was a worthwhile sacrifice.

“It’s a lot easier to BYO (bring your own) shade than BYO beach,” said Kyndall Frederick, who lives in Hali‘imaile and is the social media coordinator for the Surfrider Foundation.

Owens believes sand dunes remain “underutilized” due to lack of awareness. For a couple of decades, a handful of people with Sea Grant and “a cadre of volunteers” were at the forefront of the effort, especially in South Maui where dunes feature prominently at beaches like Kama‘ole I, II and III. However, awareness and resources have grown — the dune crew, for example, was created just a couple of years ago.

Spellman said putting dedicated staff, time and money toward keeping the shoreline resilient “shows a shift in priorities for our government” and how seriously they take the threat of sea level rise and coastal erosion.

Maui County also is working on a separate, larger master plan for long-term management of the area. Keeping the dunes healthy is “just one small sliver” in the overall effort, Derrington said.

“We can’t necessarily fix all the wrongs of the past,” Owens said. “But with the dune restoration portion of things, we are trying to sort of heal again and set ourselves up for a maybe better future.”