Hawai'i Journalism Initiative

Hawai'i Journalism InitiativeTrade wars take toll on Maui farmers and ranchers already battling deer and drought

KULA — When then-presidential candidate Donald Trump was talking about tariffs on the campaign trail in 2024, Maui rancher Brendan Balthazar borrowed some money and bought a container of cattle fencing before the prices could go up.

Sure enough, after Trump took office last year and started imposing tariffs, the cost of wire and fencing products coming from out of the country shot up. One roll of barbed wire went from $40 to $80, while a roll of woven wire climbed from just over $300 to over $400, Balthazar said.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

Now, local farmers and ranchers have to decide which is worse: paying higher costs for fencing or not preventing invasive herds of axis deer from eating their grass.

“Tell Trump call me, I’ll tell him,” Balthazar said. “I mean seriously, it really impacts.”

The tariffs that Trump has levied on allies and adversaries alike have had trickle-down effects for Maui’s farmers and ranchers, who rely heavily on products from both the continental U.S. and the global market. The uncertainty over what trade war will impact them next has created even more struggles in what’s already a difficult field.

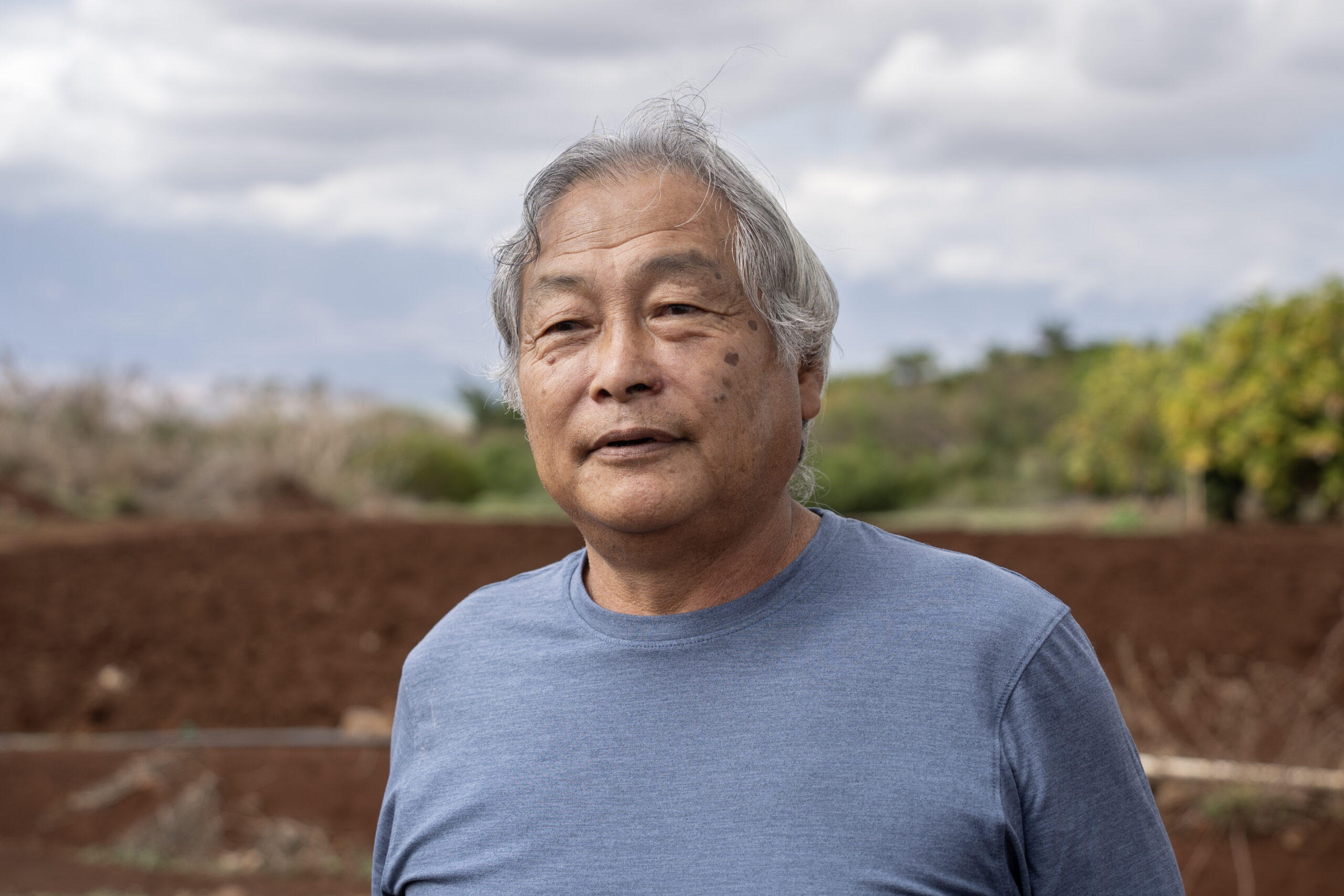

“Farming is a low-margin business,” said Wesley Nohara, a 71-year-old retired pineapple farmer who now grows kalo on a quarter-acre of land in Ha‘ikū. “I don’t know any farmer that makes 10% or more. And when your prices double, it cuts right into your margin, to the point where you might not even make any money.”

U.S. Rep. Jill Tokuda, whose district includes Maui County and who sits on the House of Representatives’ Agriculture Committee, told a group of nearly 50 farmers, ranchers and agricultural experts at the Kula Agricultural Park on Wednesday that “food security is national security.”

“Unless you can grow your own, you’re dependent on someone else,” Tokuda said. “… We have abdicated our food security to someone else, anyone else but us, and that’s a really scary proposition if you think about where we are right now at this time in the world.”

Tokuda said Democrats in Congress are trying to roll back tariffs in areas where they give the United States a disadvantage, such as with neighboring Canada and Mexico or in the Indo-Pacific region where U.S. tariffs could provide China, its trade and geopolitical adversary, with more leverage.

She and other Democrats are also is pushing for the passage of the Farm and Family Relief Act that would set aside $29 billion in economic aid for family farmers struggling with high input costs and market losses caused by Trump’s tariffs. She said more investment in agriculture is needed at the federal and state levels.

In the short term, Tokuda said, the solution is for Congress to take back the tariff powers it surrendered to Trump last year and hope that the U.S. Supreme Court will rule that Trump exceeded his authority to use emergency powers to impose tariffs. In the long term, she said, it means Democrats regaining control of the GOP-led House and Senate in the upcoming midterm elections.

“I don’t want to wait until the midterm elections because people need relief now,” Tokuda said. “We’re looking for some Republicans with courage that are going to say, ‘Look, we need to break away from the president in these particular areas of tariffs.’”

In Hawai‘i, farmers can’t just drive to the next state to get supplies. Everything has to be flown or shipped in, said Warren Watanabe, a retired cabbage and cauliflower farmer who’s now executive director of the Maui County Farm Bureau.

Before Trump’s tariffs, things were “already expensive,” especially in the years since Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Co., Maui’s last sugar plantation, closed in 2016. When that disappeared, so did the suppliers surrounding the industry. Maui used to have local dealers for things like boxes to pack produce in, but after HC&S shut down, some on-island suppliers closed and farmers had to start shipping products from O‘ahu again, Watanabe said.

Tariffs simply make those costs higher, and Watanabe said farmers are reluctant to pass that on to consumers because it hurts their chances of competing in a global market.

“Farmers and ranchers are resilient,” Watanabe said. “They adjust. Most of the time (they) don’t complain.”

Even before the tariffs were enacted, Balthazar said companies used the threat of higher taxes as a reason to hike their prices, especially as Trump went from slapping tariffs on some countries one day and taking them back the next.

Balthazar said he’s lucky “God gave me some foresight” to buy supplies ahead of time. Instead of purchasing more expensive 6-foot fencing to keep out the deer, he invested in 4-foot fencing for his cattle and additional rolls of barbed wire to put on top to deter high-jumping deer.

In the last few years, Balthazar has downsized his ranching operations from 8,000 acres across Kula, Kaupō and Ha‘ikū to about 3,800 acres, nearly all of which he leases. He has gone from a herd of about 1,000 (600 mother cows and 400 bulls and calves) to a herd of about 600 (with 400 mother cows), and has scaled back from about 500 sheep to 250 and 450 goats to 250.

Some of the cutbacks were due to deer and drought, but much of it was due to loss of land, including over 2,100 of the 3,400 Upcountry acres he’d been leasing for ranching until the state acquired it and put into conservation as part of the Kamehamenui Forest Reserve. Within a few years they’ll take the rest of the land.

“We need the land to produce the food, and we keep losing it,” he said.

Balthazar said it’s hard to justify spending even more money to improve land he doesn’t own and could potentially lose. Bigger companies can write off the higher costs from tariffs and pass them on, but smaller operations get hit harder.

As a small farmer, Nohara is used to lots of work for little profit. He used to grow taro on three different farms in Wailuku, Hali‘imaile and Ha‘ikū but the cost of transportation and managing all of the sites became too much. Now he’s down to just the Ha‘ikū farm, where he produces about 6,000 pounds a year, with about 95% going to Valley Isle Produce.

Nohara is “pretty price conscious” and noted that fertilizer costs went up during the COVID-19 pandemic but later came down during President Joe Biden’s administration. But now they’re back up after tariffs took effect under Trump. He said an organic insecticide that he bought for $115 a quart about two years ago now sells for about $225 a quart, coming out to nearly $1,000 a gallon.

Nohara’s one-man operation is already as bare bones as it gets. He does everything himself: tilling the soil, growing the crop, harvesting, delivering, accounting and paying his bills.

“My business actually doesn’t make a dime,” he said.

Whatever he makes, he uses to pay back himself. That number fluctuates, but Nohara calculated that it comes out to about $3 to $6 an hour, less than minimum wage.

Nohara, who worked for Maui Land & Pineapple Co. for almost 40 years, said the only reason he can keep farming now is because he’s retired and doesn’t depend on it for his livelihood.

“I do it really for the lifestyle,” he said. “I’m not getting rich doing it. … I want to provide good food products for the people of Maui as best as I can.”

While Tokuda and her colleagues are pushing for as many anti-tariff measures as they can, Balthazar, for one, isn’t holding out hope. With the current administration, he said, “it’s going to be really hard for Jill or any of the Democrats to reverse the tariffs.”

“Everybody knows Trump’s way, right? Trump’s way or the highway,” he said. “So it’s really great that she’s trying, but I think we should be happy if she can take small bites, a million here, half a million there … cause they’re going to give them some scraps, but it’s about what we got to deal with right now.”

Tokuda said she is not ready to throw in the towel. She sees victory in cases such as the 17 Republicans who recently voted with Democrats to extend health insurance subsidies.

Tokuda said whether it’s breaking ranks on tariffs or pushing back against the killing of American citizens by federal immigration agents in Minnesota, “we need members of Congress to have the courage to be able to do what’s right.”

“That means folks like myself continuing to push and not giving up, and recognizing that if the vote fails or the bill doesn’t pass, that just means we have to do it again,” Tokuda said. “We have to keep working at it.”

Maui County Council Member Gabe Johnson, who is also a farmer on Lāna‘i, said there are solutions locally to ease the burden on farmers and ranchers, including programs like Maui Economic Opportunity’s popular microgrants that offer up to $25,000 in aid. Applications opened this month and are due Feb. 15.

The council’s budget session is also coming up in March, offering a chance to discuss initiatives that could help local farmers and ranchers.

“I always say farmers need land, water and a little bit of capital,” Johnson said.

He plans to request funding in the budget for equipment that could be used to survey Maui for groundwater sources and identify whether it’s brackish or fresh, so the county can “make decisions based on what the reality actually is down there.”

Johnson grows a variety of crops on 2 acres that include mamaki tea, sweet onions, roselle hibiscus, okra and lilikoi. He’s seen higher costs — potting soil, for example, went from $45 for a 50-pound bag to $75 — but he’s not sure whether it’s related to tariffs or “greedflation” as companies push the limits of what consumers are willing to spend.

It’s forced Johnson to get creative. He struck a deal with a local chicken farmer who gives him manure that he uses to make fertilizer. In exchange, he lets the chicken farmer use part of his lot. But even when he finds other ways to make ends meet, the things he can’t afford, like a woodchipper, mean his operations are less efficient overall. And less products with higher costs means farmers may have to raise their prices.

“At the end of the day, that affects our community,” he said. “So now instead of buying three onions, you can only buy one onion. Or people are cutting their bills on their food to pay for their rent, and that’s not healthy.”