BLNR Passes Highly Contested Beach Nourishment Project

The state BLNR heard from the Office of Conservation and Coastal Lands on a programmatic statewide small-scale beach restoration (SSBR) permitting program that would reauthorize and expand the existing OCCL beach nourishment program to “streamline” activities.

Shellie Habel, Ph.D., presented the project — which has 19 pages of conditions — to BLNR members Friday, focusing on the OCCL’s proposed permitting structure.

The proposal included three main categories for beach maintenance operations:

- Category 1A (beach maintenance operations above mean high water line) and Category 1B (beach maintenance operations below mean high water line)

- Review Process: Application forwarded to resource agencies that can respond with both or either a request for additional information and/or recommended additional site-specific conditions and BMP’s. OCCL provides notice to cooperating agencies of findings and/or issuance of permit.

- Category 2 (beach maintenance operations limited to 1,000 cubic yards)

- Review Process: Application forwarded to resource agencies that can respond with both or either a request for additional information and/or recommended additional site-specific conditions and BMP’s. OCCL provides notice to cooperating agencies of findings and/or issuance of permit.

- Category 3 (Beach maintenance operations limited to 25,000 cubic yards & beach stabilization structure)

- Review Process: Application forwarded to resource agencies that can respond with all or either a request for additional information; recommended additional site-specific conditions and BMP’s; recommend additional project performance monitoring requirements; recommend additional marine ecosystems monitoring requirements. Notice is published in OEQC bulletin for 30-day public review which is to coincide with a public meeting in the area. OCCL provides notice to cooperating agencies of findings and/or issuance of permit

- Not covered by the SSBR are Large groins and groin files and projects over 25,000 cubic yards (such as the Kaanapali beach restoration project), long-term beach fill stockpiling for future projects, construction of new shoreline armoring structures, and actions determined for any reason to have adverse environmental or cultural impacts.

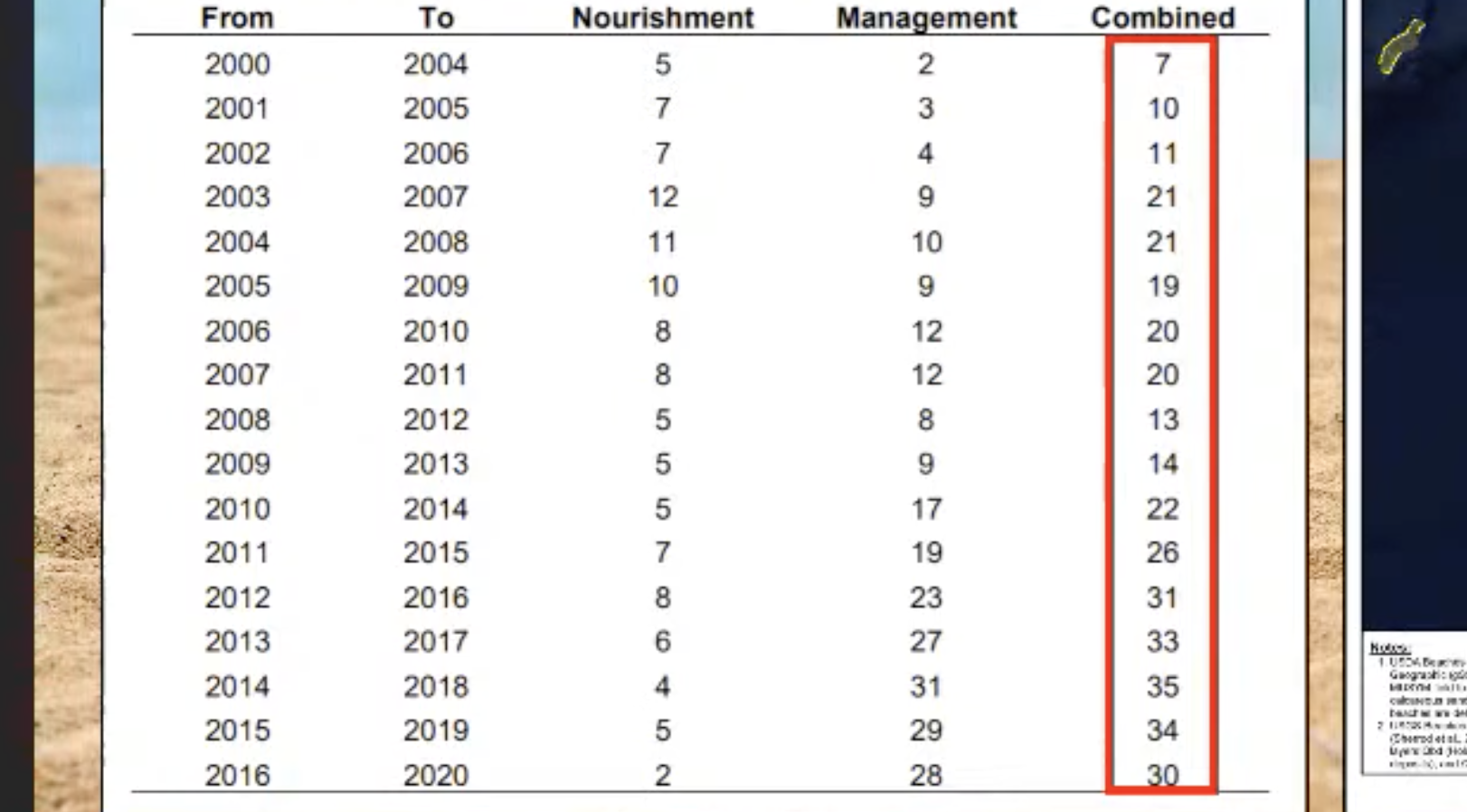

Habel highlighted that a programmatic SBBR was in place from 2005 to 2010, before the Army Corps and Department of Health ended the program, although the same application of that program is currently being used. During the time of the programmatic SBBR, more nourishment projects were permitted than are currently.

Administrator of OCCL Sam Lemmo, said that the SBBR is “an attempt to save the finite sand that we have in our coastal littoral cells but to provide some flexibility and some incentives for people to pursue smaller scale beach restoration projects, hopefully as an alternative building illegal seawalls.”

Opposition

Over two hours of testimony followed the presentation, of which, opposition surrounding the proposed beach restoration program consisted of cultural and environmental concerns.

“The community was not as informed as they probably should’ve been or would’ve liked to been informed about the SSBN program expansion,” testified Elena Bryant, an attorney at the Earthjustice Honolulu office. “That’s an important distinction. I understand that the program that was originally approved and implemented is very different than what’s currently on the table. So while this concept has been around for quite some time, we’re looking at significantly expanding that. There is a concern that the community is being left out of important planning and decision-making with respect to the management of beaches in their communities.”

“A one size fits all that categorically authorizes beach restoration activities on a statewide basis ignores unique characteristics and needs of individual beaches across the state,” added Bryant. A contingent of testimonies echoed Bryant’s comments, suggesting a more community-based permitting process.

“The scope of the category three activities is completely vague, and it’s unclear what exactly OCCL is proposing to authorize under that category. At least at this time, there don’t appear to be any limits on the type or extent of the beach stabilization structures that would be allowed under category three. These aren’t the type of activities we should be streamlining,” Bryant said.

A Maui resident and avid water-woman, Tiare Lawrence, testified before the board. “On the coastline from Kāʻanapali to Kapalua, there are several properties that have had temporary emergency sandbag revamps in place for over 20 years. Despite the fact that the revamps were authorized under an emergency special management permit as one-year temporary fixes, these revamps remain in place to this day,” she said. “The sandbag revamps have done nothing to preserve or protect the shoreline. It has actually done the opposite by causing flanking erosion to the public trust’s resources. Despite years of requests from the community for enforcement, nothing has been done to bring these properties into compliance or to remove the now-illegal revamps. Under the proposal, sandbag revamps like the ones that have plagued us in Maui will be allowed to remain in place through a streamlined and simple permitting process.”

One example of an activity that could fall under the proposed motion would be installing groins at Kalama beach on Maui, although there will probably need to be a retreat as well, according to OCCL Administrator Sam Lemmo.

Lemmo responded to some of the opposition. “Some of the comments that we’ve received are about transparency and exposure and I just don’t agree with that. Then there’s a whole discussion about the negative aspects of this project and the damage that it’s going to do and the problems that it’s going to lead to. I’m having trouble getting my head around all of that because this is resource protection, it’s resource conservation, it’s resource enhancement. The projects that we’ve done throughout the Hawaiian islands have been very successful. We haven’t seen any negative ecological effects; it actually improves habitat for marine creatures, and we monitor the benthic environment to make sure we’re not causing any undue harm to that. The turbidity of these projects all comes down to sand quality. If you have good sand quality, you’re not creating a situation much different than what happens naturally. It just happens that sometimes there are these short-term pulses of sediment because the sand is trying to bleach and bleed itself out a little bit but then it all equilibrates.”

Several letters of opposition and support were submitted before the meeting. Michele Chouteau McLean, the Maui County Planning Department Director, wrote a letter of support.

Ruling

In a BLNR roll-call vote of five to two, the motion of Item K-2 passed (with some amendments).

In favor were board members Case, Oi, Yuen, Char and Gon.

“We need to make a decision at this time. To not do anything would be irresponsible, I think,” said board member Sam Ohu Gon III.

Against were board members Canto and Yoon.

“I referenced the public trust doctrine of 1999. It clearly states that ‘the state shall conserve and protect Hawaiʻi’s natural beauty and resources,’ so I’ll be voting against the motion based on that fine line,” board member Doreen “Pua” Canto, a Kula resident who joined the BLNR last week.

Amendments to the motion included:

- Category 3 actions to be submitted to the BLNR for final approval

- Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) to be consulted on categories 1 – 3

- Private owners required to certify; do not get a regulatory shoreline certification makai of their pre-constructed shoreline for categoriest 1 – 3

- Full public trust analysis for any category 3 project

“I think those were really good points, and they address a lot of the concerns raised here,” said Chairperson Suzanne Case after hearing the amendments.

Several oral requests for a contested case were made during the meeting, and written requests can be filed 10 days following the ruling.

_1768613517521.webp)