Kīhei Community Association president hopes to overcome funding road blocks

A People Of Maui Interview: Michael Moran

In the early 1980s, Kīhei in South Maui was ranked in the top 10 among the fastest growing cities in the United States, and for good reason — it attracted visitors looking for a posh, quiet vacation or a place to retire that had less crime and wide open spaces, including an enviable coastline of 14 miles of sandy beaches. It also had enough space for reasonably priced apartments to accommodate employees who would work in the resorts.

With growth comes problems — some bigger than others, including employee housing and snarled traffic.

Kīhei Community Association president Michael Moran points out that his group has had its measure of successes in pushing forward projects that benefitted South Maui from Māʻalaea to Mākena.

The Association was able to help to secure funding for the Kīhei High School and the development of Kalama Park, including lighted path, and the creation of a South Maui Regional Park. In the 1980s, its president William Maschal pushed for the development and improvements to Piʻilani Highway in light of flooding cutting off South Maui at South Kīhei Road near the old Kīhei Boat ramp in 1979. One of its members, Gene Thompson, was instrumental in organizing volunteers to build sand fences, similar to snow fences, to slow the drift of sand onto roadways, plant native naupaka, and help to maintain the sand dunes.

The Association has been a major critic of the state Department of Education’s refusal to plan for a grade-separated pedestrian walkway crossing over or under the four-lane Piʻilani Highway — a refusal that now is delaying the opening of the Kūlanihākoʻi High School. Maui Now writer Gary Kubota conducted the interview.

KUBOTA: How important is it to have a separate pedestrian walkway crossing Piʻilani Highway and what has been the problem in getting it?

MORAN: The reason for the requirement was safety. More than 10 years ago, the state Land Use Commission realized the importance of providing a separate pedestrian walkway for students; that’s why it made the walkway a condition before the high school could be opened. The problem has been that the Hawaiʻi Department Of Education has stubbornly refused to build the crossing. When a state department funded by taxpayers refuses to follow legal restrictions, we end up with the chaos we have today. A crossing over or under the highway is vital for community safety. It is also imperative for the department to follow legal requirements.

KUBOTA: Are you satisfied with the recent agreement reached by Maui County Mayor Richard Bissen and state Gov. Josh Green to temporarily open Kūlanihākoʻi High School without the Grade Separated Pedestrian Crossing? My understanding is that the separated pedestrian crossing will take about three years to build.

MORAN: We are trying to get a clearer understanding of just what this means, as it was just announced Tuesday evening. We think this means the existing school will open August, 2023 for both 9th and 10th grades, then August, 2024 for an additional grade, and August, 2025 for all four grades. If so, how many students? Does Department of Education have sufficient school buses and drivers for transport the students, since it seems there will be no reasonable manner for any safe way to walk across Piʻilani Highway?

What has changed that the department now says the overpass will be built in three years, as it has always stated a much longer timeline to accomplish construction? Will the crosswalks and yield lights be removed at the nearby roundabout?

Does not the department need to return to the state Land Use Commission to request a motion to amend its decision, if the state is going to open the school before completing the overpass?

Our concern is for the safety of our community children. We are pleased that the newly elected governor and mayor are taking actions to try to rectify a decade of negligence by the Department of Education, but until we get all the information, it is difficult to judge.

KUBOTA: Are there other traffic concerns?

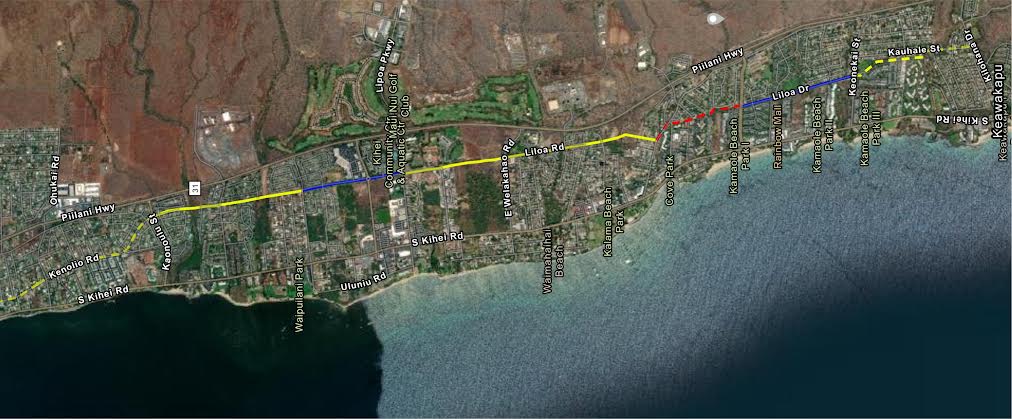

MORAN: Our association’s continuing priority is construction of the missing segments of the North-South Collector Road between Waipuʻilani and Kaonoulu as a complete street, including the extension of Līloa Road. This road has been in the Kīhei-Mākena Community Plan of 1998, including bike paths that would reduce traffic. But very little action has been taken by previous administrations. Traffic has tripled since then. We are hopeful that the current mayor will fulfill his pledge to make this a priority.

KUBOTA: I can’t help but see that low-lying areas of Kīhei continue to have flooding problems?

MORAN: Our association continues to advocate for mitigation of storm water flow Upcountry, as we have for over a decade.

KUBOTA: What kind of mitigation measures do you want?

MORAN: We want retention and detention basins to slow the flow and allow sediment to be absorbed into the aina. We want more trees and other natural foliage to absorb storm water. We want periodic clearing of river gulches of debris and for action to be taken to reduce the number of axis deer.

KUBOTA: You’ve mentioned that the vast majority of families with children are living in North Kīhei. How important is providing affordable housing throughout South Maui?

MORAN: Of course this is a nationwide matter, but exacerbated in Hawaiʻi. One factor contributing to traffic in our district is the great number of Maui residents who work in the tourist industry and commute daily into Wailea. Providing truly affordable housing in South Maui would help mitigate the already overburdened transportation infrastructure. But such housing has to be located in proper locations, not in flooding or fire prone areas nor industrial areas. They should be interspersed for mixed use neighborhoods.

KUBOTA: How does one go about encouraging mixed uses, when some landowners seem bent on creating exclusive communities?

MORAN: Developments require government approval, and a community can influence decisions by the government and sometimes developers. One example is the Wailea 670 project, renamed Honuaʻula. It went from all high end in the area south of Maui Meadows with some affordable housing developed separately south at the North Kīhei light industrial to a mix of both all in the area north of Maui Meadows.

KUBOTA: How did you come about living and settling in South Maui?

MORAN: I was born on the East Coast and spent a quarter century in Southern California. Then, I visited Maui staying on the South side, and fell in love. After a few more visits to Maui and other islands, I found Maui nō ka ʻoi. I looked for a reasonable way to be able to settle here permanently, and did so in 2000.