Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative

Hawai‘i Journalism InitiativeIn Hawaiian Electric’s first proactive power shutdown, Upcountry customers frustrated by long outage but supportive of fire prevention program

When Hawaiian Electric proactively cut the power shortly before noon on Sunday due to wildfire risk, Surfing Goat Dairy owner Jay Garnett figured his Upcountry Maui farm could weather the outage.

But when the shutoff for about 330 Upcountry customers dragged into the night, it became a major problem for the dairy farm. Without power, its machines couldn’t milk the goats or pump water. Garnett said portable generators can only do so much on a 42-acre farm with 400 animals.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

By the time the electricity was turned back on about 20 hours later on Monday morning, the farm had lost an estimated $10,000 worth of dairy products. The nearby Haleakala Creamery also lost about $2,000 in products during the prolonged outage, owner Rebecca Woodburn-Rist said.

These financial blows were a tough introduction to the first intentional outage under the Public Safety Power Shutoff program, which Hawaiian Electric launched last summer in the wake of the destructive August 2023 wildfire in Lahaina that investigators found was caused by a downed power line.

For some Upcountry customers, the length of the cautious outage was frustrating, but even the hardest-hit business owners agree the program is needed to prevent a repeat of the tragedy on Aug. 8, 2023, when wildfires destroyed 26 homes in Kula and more than 2,200 structures in Lahaina.

Hawaiian Electric first put the warning out on Saturday afternoon that Maui and Hawai‘i island customers were on wildfire safety watch and could have their power shut off due to high winds. The watch was canceled later that night, but Hawaiian Electric raised the alarm again the next morning and around noon the company shut off the power for the approximately 330 customers Upcountry

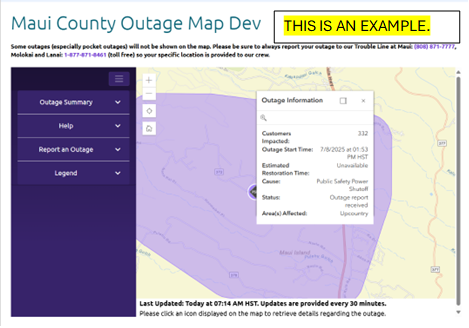

The area covered a sprawling section of ‘Ōma‘opio that includes multiple farms and ranches, according to Hawaiian Electric maps.

Mathew McNeff, Hawaiian Electric’s director of Maui County, said a high-pressure system was moving north of the islands, providing the potential for fire risk weather. To trigger a shutoff, conditions need to include wind gusts of 45 mph or higher and a relative humidity of 45% or less. There also has to be persistent drought conditions, which at the time covered 90% of Maui County.

A task force on O‘ahu, which monitors all the islands that Hawaiian Electric serves, makes the ultimate call about whether to shut off the power, based on the data from local weather stations as well as “spotters” making observations on the ground, McNeff said.

Since the 2023 wildfires in Lahaina and Upcountry, Hawaiian Electric has installed 35 new weather stations in Maui County.

“Hawai‘i weather can change so rapidly,” said Shayna Decker, director of government and community affairs for Hawaiian Electric in Maui County. “So that’s why that decision whether or not to turn off the power is done with such great care and monitoring of the weather stations in real time.”

Decker said Hawaiian Electric sends out notices 24 to 48 hours ahead of time to let customers know that they are tracking weather conditions, with follow-up messages once the decision is made to shut off power. She said people can sign up for direct alerts through email, phone messages and text messages. The company also puts updates on its social media accounts and sends out updates to news media.

For privacy reasons, Decker said Hawaiian Electric doesn’t announce publicly the exact locations and street names, but she said the outage areas are available on the company’s website, and in extended outages, they contact customers as needed.

Before bringing the electricity back on, Hawaiian Electric has to visually inspect every portion of the lines, which is what caused the extended outage, the company said Sunday night. The inspection can only be done “after the hazardous weather conditions have subsided,” and “some areas are easier to do than others,” McNeff said.

Power was finally turned back on to all customers by 8:30 a.m. Monday. McNeff said “no significant repairs” were needed. Hawaiian Electric continued wildfire watches throughout the week and only lifted them Wednesday after weather conditions improved.

At the time that the power was turned off on Sunday, some Upcountry customers said the winds were barely blowing in their neighborhood.

“The leaves weren’t even moving on the trees,” said Garnett, who called Hawaiian Electric and struggled to get more information about the threat levels that triggered the shutoff to his area but not nearby Pukalani or Makawao.

“When we had the floods last year, the power stayed on,” he said. By contrast, Sunday was “a beautiful blue sky day with no wind, but that’s the day we lose power.”

At the time of the power shutoff, the two closest Hawaiian Electric weather stations on Lower Kimo Drive and ‘Ōma‘opio Road showed winds were blowing 6 to 7 mph with gusts up to 16 mph and humidity ranging from 50% to 62% around noon on Sunday.

However, Hawaiian Electric based its decision on the Upper Division Road weather station near the Central Maui Landfill — that station monitors conditions to the circuit that provides service to the customers who were affected Upcountry, Decker said. At 11:20 a.m., the station recorded wind gusts up to 47 mph and 41% humidity, data show. Makawao and Pukalani are fed by different circuits than the one to ‘Ōma‘opio, and Decker said the weather around the stations may be different from the conditions at the homes.

Woodburn-Rist of Haleakala Creamery was in Canada for the Calgary Stampede when the power went off at her farm. She said her weather station reported no wind at the time.

The farm relies heavily on electricity to operate its fridges and freezers that are full of ice cream and cheese, and its tanks that cool the milk. When the power went off, she waited about three or four hours hoping it would return before asking her farm sitter to run the generator.

Unfortunately, the generator wouldn’t start, even with the help of a neighbor, forcing her husband to toss the spoiled products when he returned to Maui on Monday.

“It just seemed like there was no emergency reason to leave the power off all night,” Woodburn-Rist said. “But I also know that I need to be prepared because they told us that’s what they were going to do.”

Woodburn-Rist said she got plenty of notifications from Hawaiian Electric, but the problem was the uncertainty about the length of the outage.

The incident highlighted the need for her business to get a battery storage system and solar power for its commercial kitchen, because “if this is going to be the new future where they turn off the power on a whim and leave it off, then I will always lose products,” she said.

While Woodburn-Rist agrees it’s a good program now for safety reasons, she hopes “it’s not just a Band-Aid” and Hawaiian Electric is working towards making its equipment safer so intentional outages are not necessary.

“While I may have lost cheese, I know that there’s people in homes that have medical devices that need power,” she said. “And I think that would be even more scary and dangerous.”

Garnett said he also believes it is now a needed program: “I think a lot less damage would have happened if we had something in place for Lahaina.”

But, he said, “you can’t target, in my opinion, farms. The ability for my home to not have power for 18 hours is very different than trying to feed 400 animals and run a commercial dairy.”

Garnett said while his farm will have to invest in more generators, he worries about the increased reliance on fossil fuel and the risk that comes with more heavy equipment on properties.

“So you basically tell everybody we’re cutting power and you’re getting everybody to run gas generators all over the place in the middle of the brush fire,” Garnett said. “What do you think is the likelihood of something more happening? … You’re cutting the power to create another problem in my opinion.”

Others saw the power outage as a worthwhile inconvenience to prevent fires.

Jillian Vickers, owner of Jillian’s Stables, didn’t lose power last weekend but remembers the stress of having to be under evacuation warnings with 20 horses and 25 pigs for nine days with no power during the 2023 wildfires Upcountry.

“I would much prefer that the power get turned off, even if they don’t think it’s as windy as it should be,” Vickers said.

When asked if she’d gotten enough notifications from Hawaiian Electric, Vickers quipped, “probably too much.”

Sandy Takishita said the outage didn’t cause any problems at Howard’s Nurseries, where she is one of the owners. She said everybody knew the program was coming for months. The nursery lost its internet but had backup generators, and Takishita said temporarily losing the ability to email and text was “no big deal.”

“This is the way it’s going to be until the drought ends,” Takishita said. “We’ve got to face facts. I mean, I know there were plenty of people that were like, why didn’t we have more notice? And I’m thinking, hello, the winds are blowing. This is what happened when the last fire happened. … So they’re just taking preventative measures, and you can’t blame them.”

Steve Grogan, owner of Hale Kiana Bed and Breakfast, which is located in the neighborhood mauka of the dairy farms, said his business didn’t lose power but that if it had, he would have likely had to reimburse his guests. Grogan was attending Waipuna Chapel on Sunday for a Fourth of July barbecue when the power went out, deflating a kids bounce house and leaving the DJ with no electricity. They were still able to enjoy watermelon and burgers cooked on gas grills.

Grogan said he understands the need for the program but that it should be “custom-tailored to reality” and not a blanket shutoff.

“They’re covering their butt so that they don’t have a horrible, horrible incident … and I understand that,” Grogan said. But, he said, he thought they overreacted by keeping the power off all night.

Regardless of their experience, many hoped to see a more permanent solution beyond the power shutoff program.

Stacey’s Garden, which makes salad dressings, had been storing a few hundred bottles of dressing at a leased Upcountry property. Josh, the company’s manager, who declined to give his last name, said when he got the message about the electricity going off, he drove Upcountry and loaded all of the bottles into his car to take to Kahului for refrigeration. At the time, there was no wind, “nothing like the day of the fires,” he said.

“I don’t know what the long-term solution is here,” he said. “In 50 years, are we still going to be facing the same thing where every time the wind blows, Upcountry loses power? Or are they going to fix it? But I’m sure it’s super expensive to fix it, bury the cables, bury the electric wires.”

Decker emphasized that turning off the power is a last resort for Hawaiian Electric and that the utility is working on other programs to reduce the risk of fire. Last month, the company released an updated $350 million, three-year plan to reduce wildfire risk, particularly on Maui, through new weather monitoring technology, upgraded equipment and underground power lines in some areas of Lahaina.

“It really is our last line of defense to proactively turn off the power before hazardous conditions are experienced,” Decker said of the power shutoff program. “And so that’s why we’re doing all the other mitigation work from installing the cameras to doing different vegetation management.”

She urged people to sign up for alerts from Hawaiian Electric, including those with special medical needs, who can fill out a form to get additional advance notifications of a power outage. She said more than 420 customers have signed up for medical notifications on Maui.

Over the last year or so, Hawaiian Electric has been giving presentations to communities covered by the power shutoff program “to try to make sure everyone is aware and no one was caught off guard,” McNeff said.

McNeff said Hawaiian Electric’s first intentional power shut off showed “we were able to execute when we saw the conditions that were conducive to fire weather, and as a result of that, nothing bad happened. There were no ignitions associated with Hawaiian Electric’s equipment. And that’s really the goal. We’re trying to keep people safe.”

But he said the utility continues to refine the process, and has stood up a team several times in preparation to potentially shut off the power. After each deployment, the company does an after-action report. Decker said the report from the latest outage is being put together and will become public record once it’s submitted to the state Public Utilities Commission.

“We go over the things that maybe we could have done a little better,” McNeff said. “And we try to get better each time.”