Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative

Hawai‘i Journalism InitiativeMemory of 2023 wildfires taught Maui community, government to respond more urgently to tsunami warning

Less than 10 minutes after receiving the alert that the entire State of Hawai‘i was under a tsunami warning on Tuesday afternoon, The Old Lāhainā Lūʻau canceled its evening show, called off about 100 employees and pulled the 180-pound pig out of the imu early.

Nā Hoaloha ‘Ekolu, which operates the lūʻau, Aloha Mixed Plate and Star Noodle right next to the shoreline, doesn’t take any chances when it comes to emergencies these days — not after the 2023 wildfires spared its businesses but destroyed much of Lahaina town.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

Government officials and the general community seemed to take the same caution in the hours after the warning, as evidenced by the mass evacuations, business closures and frequent warnings from state and county officials.

Already in the back of most minds was the fast approaching two-year anniversary of the deadly fires on Aug. 8.

“Residents of Maui take things so much (more) seriously now,” said Kawika Freitas, the company’s director of public and cultural relations.

The tsunami on Tuesday was generated by a massive magnitude-8.8 earthquake off the coast of Russia, which ranked among the top 10 largest ever recorded by the U.S. Geological Survey.

But after hours of quick response, congested roads and concern, the tsunami only caused minor flooding at Keālia Pond National Wildlife Refuge and caused water levels at Kahului Harbor to drop about 15 feet as the ocean receded. No significant damage or injuries were reported, according to Maui County officials, who declared the all-clear at 10 a.m. on Wednesday.

The National Weather Service issued a tsunami warning at around 2:45 p.m. on Tuesday, with the first waves expected to hit the islands at 7:10 p.m. The outdoor all-hazard warning sirens, which became a major point of contention in 2023 after they weren’t activated during the Lahaina fire, sounded at least three times before the arrival of the first wave.

“This was professionally handled and well executed with a lot of notifications, alerts,” said Javier Barberi, a partner in Hana Hou Hospitality, which owns multiple restaurants in West Maui. “They rang the sirens. They sent the text messages. The news had it all over the news websites with updates. So yeah, this is day and night compared to how they handled the fires.”

Maui Veterans Highway quickly clogged up as residents evacuated from low-lying South Maui, with some cars pulling off the road and racing down the greenway to get past the traffic.

Unlike the day of the fire, Nell Laird-Woods didn’t wait to evacuate. She lives in the neighborhood across from the Lahaina Aquatic Center, which is in a red evacuation zone, the area of highest risk during a tsunami. When she realized the warning wasn’t lifting anytime soon, she scooped up her two dogs, her medications and a change of clothes and left her home around 5 p.m.

“I was way more cognizant of the fact that this is nothing to mess around with,” Laird-Woods said. “Mother Nature is going to do what Mother Nature is going to do.”

Laird-Woods said “the timing could not be worse” coming two years after the fire. But, she noted, this time around, communications with the public “vastly improved,” though she pointed out that at least there was cell service, unlike on the day of the fire. She got notifications on her phone and listened to an update from Mayor Richard Bissen on the radio as she drove to a friend’s house in Kahana, where she had stayed for nine months after the fire.

“They learned this time and took it to heart, and they have made massive improvements,” said Laird-Woods, who returned home around 9 p.m.

At the Old Lāhainā Lūʻau, Freitas said the quick decision to close was due to “post-traumatic reminders of the fire.” They wanted their employees to get home, and they didn’t want visitors adding to the traffic of residents fleeing to safety.

“That is because of what we learned from the fires,” he said. “Don’t mess around, just do it and be safe and get people off the road.”

Freitas said they have procedures for hurricanes and tsunamis that include shutting off their gas and water and tying down their equipment. The last employees stayed to pull the pig out of the imu about an hour and a half early, shred the meat and put it into the fridge.

When they returned, they found no damage to the property.

Barberi actually thought the tsunami warning notification was a joke when he first got it, recalling the 2018 false missile alert that sent the whole state into a panic. But when he realized how big the earthquake was and thought back to the wildfires of Aug. 8, 2023, he knew he had to take the threat seriously.

“Having gone through the fires in Lahaina … this is like another disaster looming on the horizon, and it’s just like ugh, we have to go through something like this again? Like haven’t we been through enough?” Barberi said. “So this makes it more impactful and feels more serious.”

Within roughly an hour of the warnings, the owners made the decision to send their employees home and close their seaside restaurants — Mala Ocean Tavern, Coco Deck and Honu Oceanside on Front Street. They shut off the gas and water and hoped for the best. Barberi said sandbags and other barriers wouldn’t help. Mala has too many openings.

Fortunately, there was no damage to the restaurants.

The fires weren’t only on the minds of West Maui residents and business owners.

On the other side of the island, the new restaurant Aurum Maui in The Shops at Wailea sent all 11 on-duty employees home within an hour of the tsunami warning, according to general manager Natasha Ponte and executive chef Taylor Ponte, a husband-wife team.

The decision came quickly for the Pontes. They were driving forces behind a program to feed Lahaina and Kula wildfire survivors after the deadly fires, coordinating the preparation of thousands of meals per day.

“It was an easy decision for me because I’m exhausted,” Taylor Ponte said. “We’ve been going for almost three months straight. At the end of the day, we’ve been through so many tragedies together.”

Taylor Ponte added, “At the end of the day, ‘it’s like, go home and be with your families.’ That’s an easy call for us. It sucks we have to close and we want people to come and see the restaurant. That’s hard. When it comes to the call, we care about our staff. We want our staff to feel safe.”

Natasha Ponte said the government response was well coordinated, saying, “I think they were being extra precautious because of where we were two years ago.”

“I think they felt — pardon my language — a little fire under their ass,” Natasha Ponte said. “They felt the need to respond appropriately, which should be the case every time.”

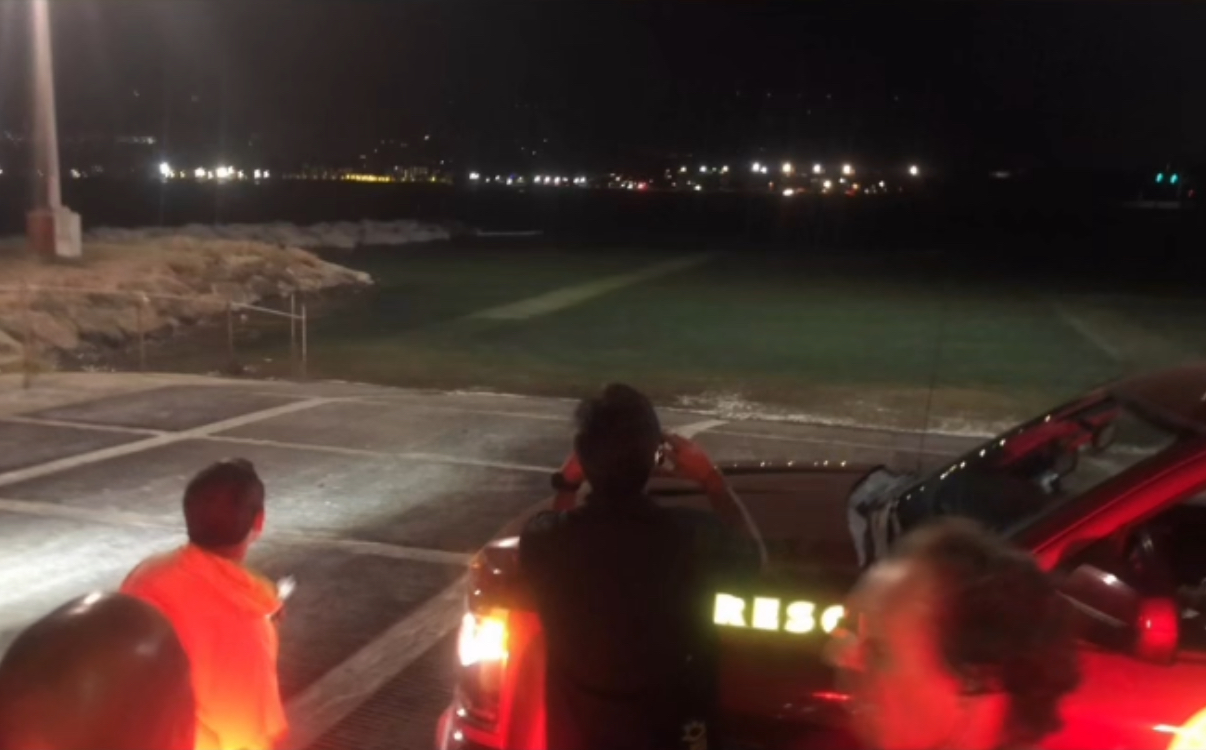

In just about every coastal town, residents took action. At Ka Lae Pohaku Beach Park in North Kīhei, the Kihei Canoe Club moved about a dozen of its canoes to the grassy area on the soccer/baseball fields at Kenolio Park.

Across the street at the retail space that used to house Suda’s Store, Ululani’s Hawaiian Shave Ice closed at 2:30 p.m. on Tuesday — four hours early — and sent six employees home.

The ABC Stores location next door closed at 3 on Tuesday, and all eight of the employees on duty were out by 3:30 p.m. The usual closing time for the store is 10 p.m. Three sandbags were still next to one of the front doors.

There was no damage to either North Kīhei business.

Across the island in Hāna town, which also hugs the coast, the Hasegawa General Store stayed open until closing time at 6 p.m. on Tuesday. Owner Neil Hasegawa was the only one of the six store employees on duty to leave early because his home on Haneo‘o Road rests within 100 yards of the ocean between Hāmoa and Koki beaches, and he wanted to “start bundling up my house.”

Hasegawa and his wife Mitzi evacuated to a cousin’s house to watch the expected waves roll in, but they never really did.

“I stayed by the Hāmoa bus stop that the hotel uses to pick up their guests,” Neil Hasegawa said. “And I stayed there until 7:45 and was just waiting to see that the water recede, but … it was nothing. It was no effects at all. I was kind of surprised.”

When the expected arrival time of the first wave to reach Maui County came and passed at 7:17 p.m., he didn’t see any noticeable surge. When he awoke Wednesday morning, he didn’t see anything startling.

“The debris wasn’t anything special,” Hasegawa said. “It was like when we get the king’s tide with a super-high tide, that’s how high it came across the road.”

Hasegawa added, “it wasn’t going into anybody’s yard or anything like that. So, it was kind of surprisingly a non-event.”

He is not upset that the event happened and was glad that the warning system is in place and that state and county governments treated it quite seriously.

He stayed on the phone via text messages overnight with his daughter Caelyn, who is away at school at Missouri Southern State University in Joplin, Mo.

“It was scary, but what was good was it was a good dry run,” Hasegawa said. “Because I’m sure another one is going to hit us.”