Hawai'i Journalism Initiative

Hawai'i Journalism InitiativeHawaiʻi wildfire plan in the works in conjunction with expansion of new state fire marshal’s office

A plan that aims to overhaul how state agencies prepare for wildfires is expected to be completed in early 2027, according to the Hawai‘i Wildfire Management Organization.

The Hawai‘i Island-based nonprofit is working with each state department to redefine its approach in hopes of preventing another tragedy like the August 2023 wildfire that killed at least 102 people in Lahaina.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

“Our fire risk has increased and outpaced our policies, our actions, our protocols, etc.,” said Elizabeth Pickett, co-executive director of the organization. “So the idea is to catch everybody, every department up to the role … it should be playing.”

From the hundreds of recommendations that came out of the investigations into the 2023 wildfires, the state selected 10 priorities and hiring the organization to coordinate Hawai‘i’s improved approach to wildfire prevention was at the top of the list. The third and final report on the fires was released in January 2025.

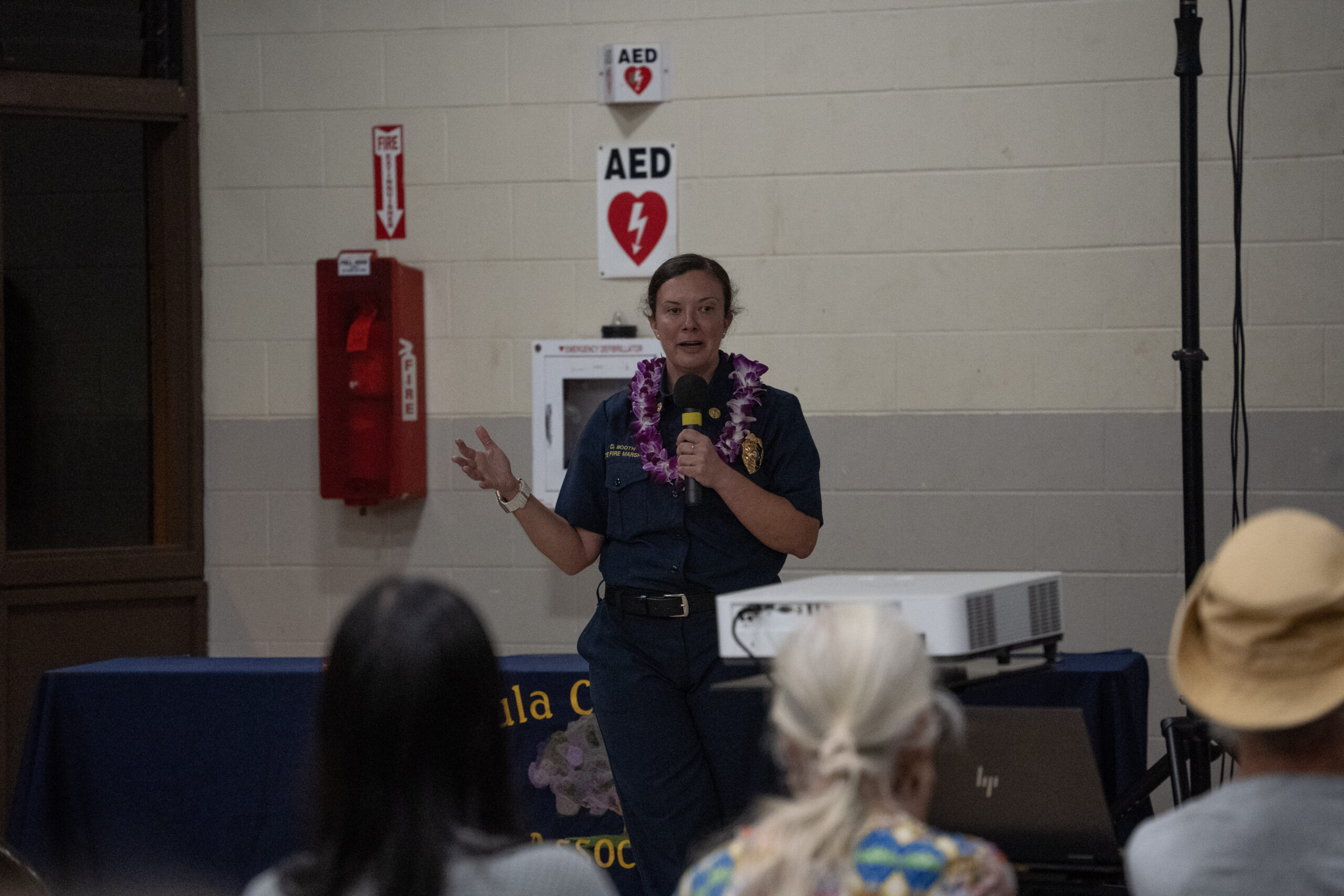

The second key move was hiring Dori Booth over the summer to serve as the first state fire marshal in nearly 50 years.

The other eight priorities are wildfire education programming, communication systems, utilities risk reduction and planning, fire weather, evacuation, codes and standards, wildfire response preparedness, and vegetation and land management.

In 2026, both the Hawai‘i Wildfire Management Organization and the growing State Fire Marshal’s Office will be critical in laying the groundwork for safer, more prepared communities.

Before the 2023 wildfires destroyed more than 2,000 structures in Lahaina and over two dozen in Kula, fire prevention “wasn’t front and center” for the departments that don’t have to deal with it on a regular basis, Pickett said. Now, that focus has changed, and there is widespread understanding that fire safety “needs to be systemwide.”

The organization has already met with every department, and each agency has already turned in initial drafts of their plans, Pickett said. The upcoming year will really focus on coordination between departments and reducing overlap and competition.

“This year is really about identifying the optimal role everyone can play, and then figuring out the steps it’s going to take to get there,” Pickett said.

The organization has long been focused on community education, but Pickett said this year will also include training and workshops for department heads and other professionals on how the fields of planning, health, education and other sectors intersect with wildfires.

Some departments have already started taking steps toward improvements, Pickett said.

For example, shortly after the 2023 fires, the state Department of Hawaiian Home Lands coordinated an event with representatives of every homestead community in the state to learn about wildfire risk and mitigation and be encouraged to join the national Firewise program. The department has also sought grant funding to help support mitigation projects in homesteading communities and has hired a Firewise coordinator focused on Hawaiian homesteads.

The state Department of Land and Natural Resources, whose Division of Forestry and Wildlife helps respond to wildfires, also got a boost in funding and expanded authority following last year’s legislative session. The department is currently working on efforts to reduce hazardous vegetation on state lands and add fire prevention and response resources like water tanks and fuel breaks, according to a December report to the State Legislature.

As the organization works to hammer out the plan, with a final draft expected in February 2027, it will also be working closely with the State Fire Marshal’s Office.

Hawai‘i did away with the fire marshal’s role in 1979 and instead opted for a State Fire Council that included the heads of all the fire departments and the airport firefighting sector. Restoring the state fire marshal’s office will allow fire chiefs to focus on running their local departments while the fire marshal leads and implements prevention programs across the state, Pickett said.

After the unexpected death in December of Hawai‘i County Fire Chief Kazuo Todd, who chaired the fire council, Booth will assume the role as chair when the council meets later this month.

Booth said Todd’s passing “is going to be felt,” and that he wouldn’t want any fire-related planning efforts to be “put on the backburner or stop because of his passing.”

“So we definitely have to carry the torch,” Booth said.

The 42-year-old Booth, who grew up as the daughter of a firefighter in Elmwood, Ill., said that in her first six months on the job, she has been focused on building relationships and learning the key players in local government.

“Now with a state fire marshal, we have somebody that’s kind of driving the bus, forward thinking, watching for trend changes, and has that overall strategic-level view to help reduce the likelihood of the severity of something like (Lahaina) again,” Booth said.

One of Booth’s first orders of business will be to hire a team that will eventually include one deputy, an office assistant, two inspectors and three investigators. Booth said last week that she plans to do interviews for an office assistant within the next couple of weeks and hopes to post the job opening for other positions soon.

The office will have a budget of $2.2 million to start, and one of its most crucial tasks will be overseeing inspections for more than 8,000 statewide buildings. Booth said her office plans to tackle that daunting mission by doing a statewide community risk assessment that will involve identifying the types of buildings in the state, categorizing them by their hazard severity and determining which facilities require regular inspection, such as schools, hospitals and other public services, and which are lower risk and need less frequent inspection, such as state park toll booths.

But even if she could hire a full team today, Booth said it still wouldn’t be enough to cover the required work. Even if they only focused on state building inspections, the amount of research, follow-up, documentation and travel “would be impossible to do” in one year.

“Fire prevention is grossly understaffed pretty much everywhere that you go, because funding goes to frontline firefighters,” Booth said. “And it makes sense in my mind, too. It’s hard for us to say, ʻLet’s pull somebody off the fire truck to go do an inspection.ʻ”

Maui Fire Chief Brad Ventura said the department has shared the county’s operations and prevention efforts with the state fire marshal during the course of several meetings with the department and the community as well as site visits. Ventura said Booth has come to Maui multiple times during the first months of her tenure.

“Each county in Hawaii has very different needs and county specific challenges,” Ventura said via email last week. “Building a strong working relationship and understanding how we can help each other make Hawaiʻi a more fire resilient state is a major goal.”

Ventura said the ways that the Fire Marshal’s Office could help the department is when it comes to inspections of state-owned properties, which the fire marshal could follow up on and ensure that state agencies bring their facilities up to code. He added that the office could also bring in additional training for local fire investigators to help strengthen their skills and knowledge.

Booth acknowledged that one of the biggest challenges local fire departments face is the “geographical hindrance” that keeps them from training together regularly and bringing resources quickly to help fight fires the way departments can on the Mainland.

As the Maui Fire Department and other departments invest in more equipment and firefighting vehicles after Lahaina, Booth said the state could explore more ways of quickly shipping equipment between islands as needed during major fires.

But Booth said it is likely each county department is “going to be on their own” with the resources they have during the initial attack of 24 to 48 hours.

“But during those first 24 to 48 hours, that’s when we can really start looking at how do we get additional resources to move from the continent, other islands, without depleting their resources?” Booth said. “And do we have master cooperators, contracts in place similar to like on the continent … where as soon as a wildfire happens, you get an order to support a team and you’re on your way there?”

Staffing is the easiest to move. In the days after the Lahaina fire, other Hawai‘i departments sent crews to help with search and rescue.

But what ultimately helps a department handle the initial attack on their own is the pre-fire conditions. As Lahaina rebuilds after the fire, there is a chance to change “the way that our built environment looks to withstand future catastrophic fires,” Booth said.

She got her start in the fire service by helping to inspect buildings during a construction boom in Phoenix, Ariz., in 2004, eventually working her way up from intern to deputy fire marshal of the Phoenix Fire Department for 17 years. She then worked as a division chief of community risk reduction and fire marshal of the Sedona Fire District for three and a half years before taking the job in Hawai‘i.

With her background in fire codes and inspections, she hopes to help the counties review and adopt fire codes to help prevent wildfires in wildland urban interfaces, which is the area where open land starts to mix with development as it did in the Lahaina and Kula wildfires. These codes are common in places like California where fires in the wildland urban interface have destroyed towns like Paradise, which in 2018 saw the deadliest fire in the U.S. prior to Lahaina.

Last year, Kaua’i County passed new standards for home hardening and defensible space in what was the first wildland urban interface law in the state.

That means making sure communities are developed in appropriate areas with multiple access points for evacuations and fire vehicles, that homes are following the best practices on landscaping and keeping their properties free of fire-prone clutter, and that residents are prepared with their own emergency equipment and evacuation plans.

Pickett said the efforts of the community to make their own properties and neighborhoods defensible are a major step they can take to help prevent fires from spreading while efforts like the state wildfire plan and expansion of the fire marshal’s office are underway.

Local communities have taken that charge seriously since the 2023 wildfires. In 2016, Pickett’s organization helped the first three communities on Maui get certification under the Firewise program, which aims to help residents increase wildfire safety and awareness in their own neighborhoods. Since the 2023 fires, interest in the program has shot up, going from 15 to 42 communities as of 2025, with 11 more in the process.

Pickett said there’s a misconception that fire prevention “belongs to firefighting and fire departments.” But when the rest of the system, from local neighborhoods to state departments, is proactively devoted to safety and prevention, it eases the burden on fire departments who may not have the resources to rescue every structure in a major blaze.

The state fire marshal’s office “serves a very important role of having authority over the prevention side of the government response, and that’s a really important piece,” Pickett said. “It’s not the only piece. There’s still so much every one of us who lives in Hawai’i needs to do around our homes, our yards, our businesses, in preparing our families, managing our lands. There’s tons that everybody else needs to work on.”