SPONSORED CONTENT

HomeAid Hawaiʻi on Housing: Deeply Affordable Housing

Do you remember when rent was only $500 per month?

It might be difficult to remember, since the last time the average cost of rent on Maui was

anywhere near that level was in the 1980s. At that time, $500 marked the upper edge of

affordability for many working households.

Today, it is nearly impossible to find housing on Maui anywhere close to that price. Housing that rents for $700 per month or less is generally referred to as deeply affordable housing.

Most people have never heard the term because, in practice, it barely exists.

What is deeply affordable housing?

Deeply affordable housing is housing targeted to the lowest-income individuals and families, specifically those earning at or below 30% of Area Median Income (AMI).

What does 30% AMI actually mean?

In 2025, earning 30% AMI or less on Maui is roughly $30,000 per year.

Here are the current income limits by household size:

Maui County AMI Income Limits (2025)

| AMI Level | 1 Person | 2 Person | 3 Person | 4 Person |

| 30% AMI | $28,290 | $32,310 | $36,360 | $40,380 |

| 60% AMI | $56,580 | $64,620 | $72,720 | $80,760 |

| 80% AMI | $75,440 | $86,160 | $96,960 | $107,680 |

| 120% AMI | $113,160 | $129,240 | $145,440 | $161,520 |

Source: Maui County AMI Income Limits, DBEDT 2025

Who earns under $30,000 per year?

More people than you think.

This includes kūpuna on fixed incomes, former foster youth, people with disabilities, caregivers, service workers, part-time workers, and minimum wage workers.

Statewide estimates show that about 88,000 workers in Hawaiʻi earn minimum wage or near

minimum wage.

With a civilian workforce a little above 80,000 on Maui, estimates suggest that about 10% to

12% of the workforce, or roughly 8,000 to 9,600 people, earn wages at or near the minimum.

Does that mean 9,600 people are homeless? Probably not.

But it raises an important question.

If income at this level is not enough to afford housing, where do people go?

Benefits Cliff

Many households earning at or below 30% AMI rely on assistance just to stay housed. But that

support can be fragile. Earning slightly more can mean losing benefits before income is high

enough to replace them.

Instead of moving forward, progress can turn into a setback.

Deeply affordable housing changes that dynamic. When rent remains truly affordable, people

can increase income, build savings, and reduce reliance on assistance without risking housing

loss.

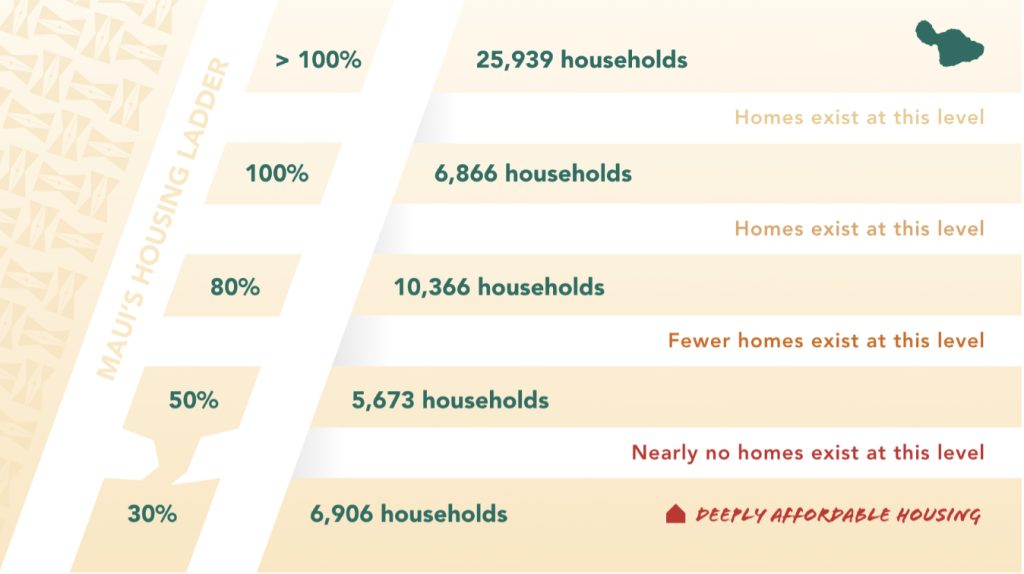

The housing ladder problem

To understand the scale of the need on Maui, here is the estimated housing demand by income

level:

Estimated Housing Demand by AMI Level (Maui)

| AMI Range | Owned | Rentals | Total Needed |

| ≤30% AMI | 890 | 2,239 | 3,129 |

| 30% to 60% | 964 | 2,308 | 3,272 |

| 60% to 80% | 1,084 | 811 | 1,895 |

| 80% to 120% | 914 | 649 | 1,563 |

| 120% to 140% | 922 | 286 | 1,208 |

| 140% to 180% | 984 | 488 | 1,472 |

Source: HHFDC, 2024 Hawaiʻi Housing Planning Study

And here is the current household distribution on Maui by income level:

Households by AMI Bracket (Maui)

| AMI Bracket | Households |

| >100% AMI | 25,939 |

| >80 to 100% | 6,866 |

| >50 to 80% | 10,366 |

| >30 to 50% | 5,673 |

| 0 to 30% | 6,906 |

Source: Maui County 2025–2029 Consolidated Plan

If nearly no homes exist at the lowest income level, where do people go?

When housing does not exist at the lower rungs of the ladder, people are forced to adapt.

They couch surf.

They double-up.

They move away.

They live in unsafe conditions.

And some become homeless.

This is not because they failed. It is because the rung below them was never built.

Why housing matters beyond homelessness

Housing is often framed as a homelessness issue, but it is much bigger than that.

What happens to someone’s health when they have no stable place to live?

What happens when someone finds a job but has nowhere to sleep?

What happens to public safety when survival becomes daily life?

Without housing:

- Emergency response becomes the default system

- Health care costs rise

- Enforcement replaces prevention

- Recovery becomes impossible to sustain

Housing does not solve everything. But it is the foundation.

Does deeply affordable housing exist on Maui?

Yes. But very little.

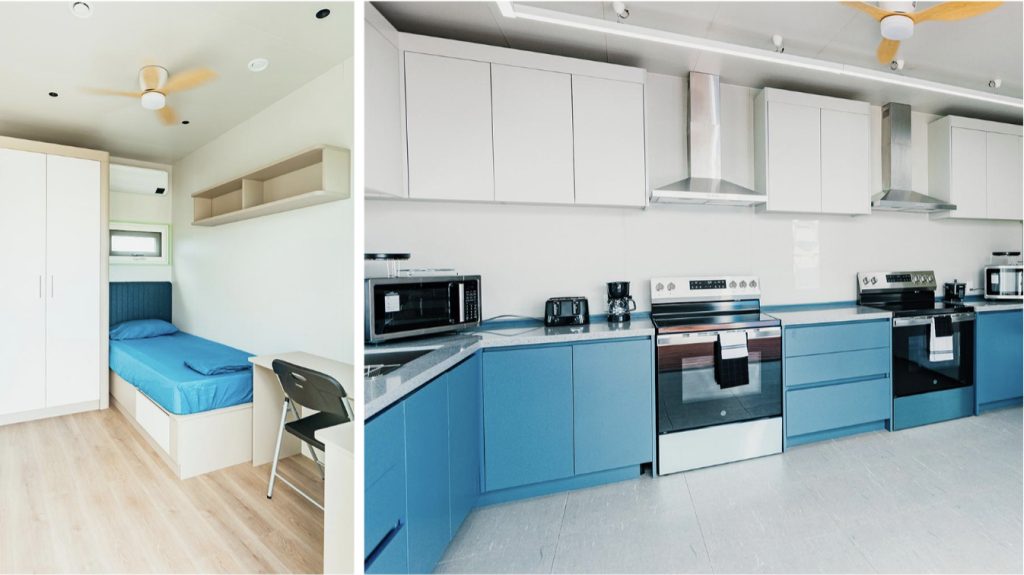

One example is Kīpūola Kauhale, a small community on Maui designed to serve people earning

at or below 30% AMI. It offers deeply affordable housing through a structured program model

focused on stability and safety.

Kīpūola Kauhale offers tiny home units with shared communal facilities.

In Hawaiʻi, organizations like HomeAid Hawaiʻi focus on making deeply affordable housing

possible by intentionally reducing the cost of construction. This is done through a combination of emergency proclamation savings, support from the State, support from the building industry, donated land, private fundraising and grants, value engineering, and community volunteers. Together, these approaches lower upfront costs and allow housing to be created for income levels the market does not otherwise serve.

This type of housing does not happen by accident. It requires intention. It requires building for

incomes that cannot support market rents. And it requires treating housing as a starting point,

not a reward.

Housing does not solve everything. But without it, everything else gets harder.

HomeAid Hawaiʻi is a local 501(c)(3) non-profit community developer dedicated to building "deeply affordable" housing for individuals experiencing or at risk of homelessness. Founded in 2015, it operates as the 15th affiliate of HomeAid America, a national network that leverages the expertise of the building industry to combat homelessness.