Hiroshi Arisumi: One of Maui’s Surviving WWII Vets

Cy Yoshizu is a journalism student at the University of Hawaii Maui College.

By Cy Yoshizu

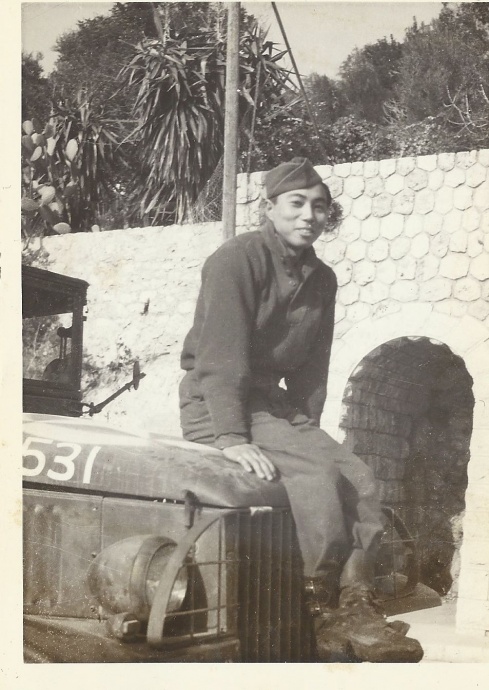

Hiroshi Arisumi lives a simple and peaceful life at his residence in Kula. A retired carpenter and handyman, he spends his afternoons tending to the fruit trees that thrive on his property.

But many don’t know about Arisumi’s past: he’s a World War II veteran, and also serves as the board chairman for Arisumi Brothers, Inc., a commercial construction company that—after five decades—thrives just like his beloved fruit trees.

He may look small and frail at the age of 92, but he is still strong and full of energy. He is a man of few words, but as he began telling us stories about his past, his words became the vessel that carried us back to another time and place.

Arisumi came from humble beginnings, working as a carpenter on the Hawai‘i Commercial & Sugar (HC&S) plantation, building and repairing homes for plantation workers and occasionally building bridges across canals. During his free time, Arisumi would surf at Kalama Park with his friends, and he claims to be the first person on Maui to make hollow surfboards, which was a great innovation at the time (surfboards weighed around 100 pounds and were often twice the size of a person).

Arisumi said he would surf whenever he had the chance to, but there was no daily surf session on Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941.

“I was going to go surfing with my friends that day, but then we got word that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor,” he explained. “We decided that it would be best just to stay home. But we couldn’t surf after that day, since we couldn’t get gas for our truck to go to the beach.”

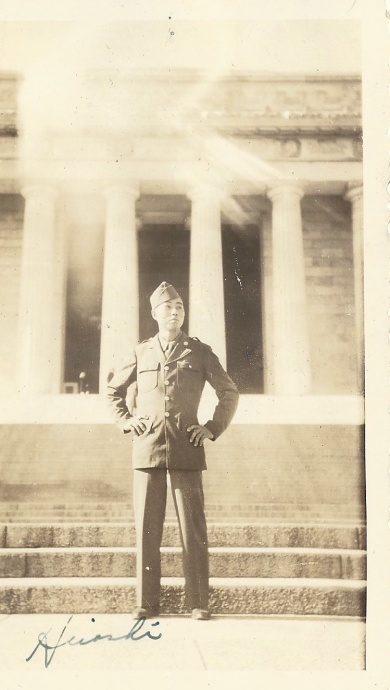

Two years later, Arisumi enlisted in the US Army, joining the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the same Japanese-American combat unit that Hawaii’s Senator Daniel Inouye fought with.

It would change his life forever.

It would change his life forever.

“The 100th Battalion was already in existence, but the Army stopped taking in Japanese Americans because they didn’t trust the Japanese,” he said.

“But the 442 was made to prove that we [Japanese Americans] would fight. The Army wanted 3,000 men from Hawai‘i, but over 10,000 volunteered.”

The 442nd Regiment traveled to Camp Shelby in Mississippi for basic training, at a time when prejudice against Japanese Americans was at an all-time high, due to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“There was no discrimination [on base],” Arisumi recalled. “Aside from the Japanese-American battalions, there were also Russian and African-American divisions. They were all integrated because they all felt they were fighting for the same cause.”

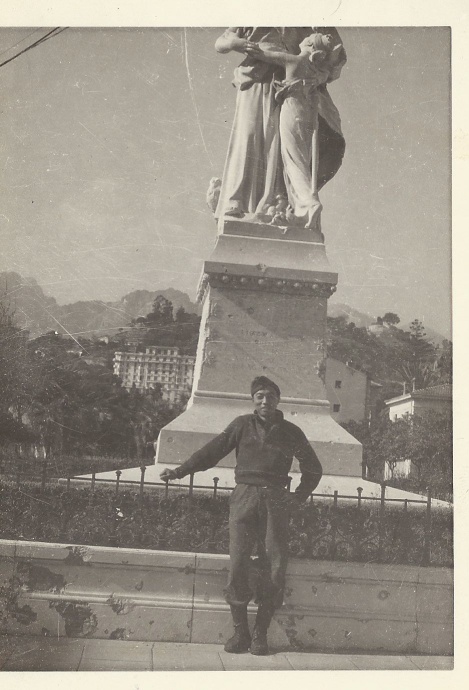

After basic training ended, the unit traveled to Italy and France, where Arisumi was given the job of combat engineer. He had to do everything that an infantry man did, but also had to create mine fields, build bridges, and make roads for tanks and supply vehicles to travel on. He even had to dive in rivers and canals to feel for cleverly hidden mines with his bayonet. Arisumi said the German soldiers were smart and cut down large trees to block roadways, so it was their job to clear the roads.

On being engaged in battle, Arisumi said, “Nobody said they couldn’t be scared, because everyone was scared. So you had to do what you had to do, and shoot back if they were shooting at you.”

While he was in France, Arisumi said his unit received word that a battalion of troops that had been surrounded by Nazi forces. The 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment (Texas Army National Guard) had been trapped by German forces in the Vosges Mountains for two days, and the 442nd Regiment was assigned to rescue them. After ascending the steep hillside and after two days of fighting, Arisumi and his comrades earned their spot in the military history: they rescued the “Lost Battalion,” despite losing many men.

And then, on May 1, 1945, the war was over.

While slowly crossing the Atlantic to return home, Arisumi said he and his fellow soldiers talked about their goals and ambitions, and what they would do when they returned to Hawai‘i. Arisumi said this experience inspired him—and so many others—to live life to the fullest.

“The sad thought of knowing that some of the guys never came back gave us the drive,” he said.

When Arisumi returned to Maui, he worked for the Army and Navy as a carpenter. The reserve unit on Maui was a construction engineer reserve, which helped him develop his skills even further. Soon after, he was offered a job at the sugar plantation as a supervisor, but he graciously turned it down to start his own company, Arisumi Brothers, Inc. He said one of his top priorities was to begin construction of the Nisei Veterans Memorial Center in Kahului, a living memorial to the brave World War II soldiers who sacrificed so much for their country.

“It was constructed to honor all the men that didn’t return home from the war.”