Hawai'i Journalism Initiative

Hawai'i Journalism InitiativeOld military fueling station, other abandoned Maui sites targeted for potential testing, cleanup and future public spaces

PAUKŪKALO — When Leiana Sing-Keliikoa was growing up in the Paukūkalo Hawaiian homestead community in the 1980s, she could see the National Guard armory from her front door.

She watched military Jeeps rumble into the lot to refuel and heard the shouts reverberating from the training exercises. She listened to her grandma and people at community meetings complain about the noise and how the space could’ve been used for more homes in the Central Maui town near Wailuku.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

“I don’t think I’ve ever heard anybody say good things about wanting it in the neighborhood,” Sing-Keliikoa said.

So when the armory shut down and the state Department of Hawaiian Home Lands acquired the 1.77-acre plot of land in 2010, residents were eager to do something with it. The department talked about turning it into a community center. But nearly two decades later, the lot is empty and stubbled with asphalt and dead grass, and neighbors aren’t even sure what’s underground anymore.

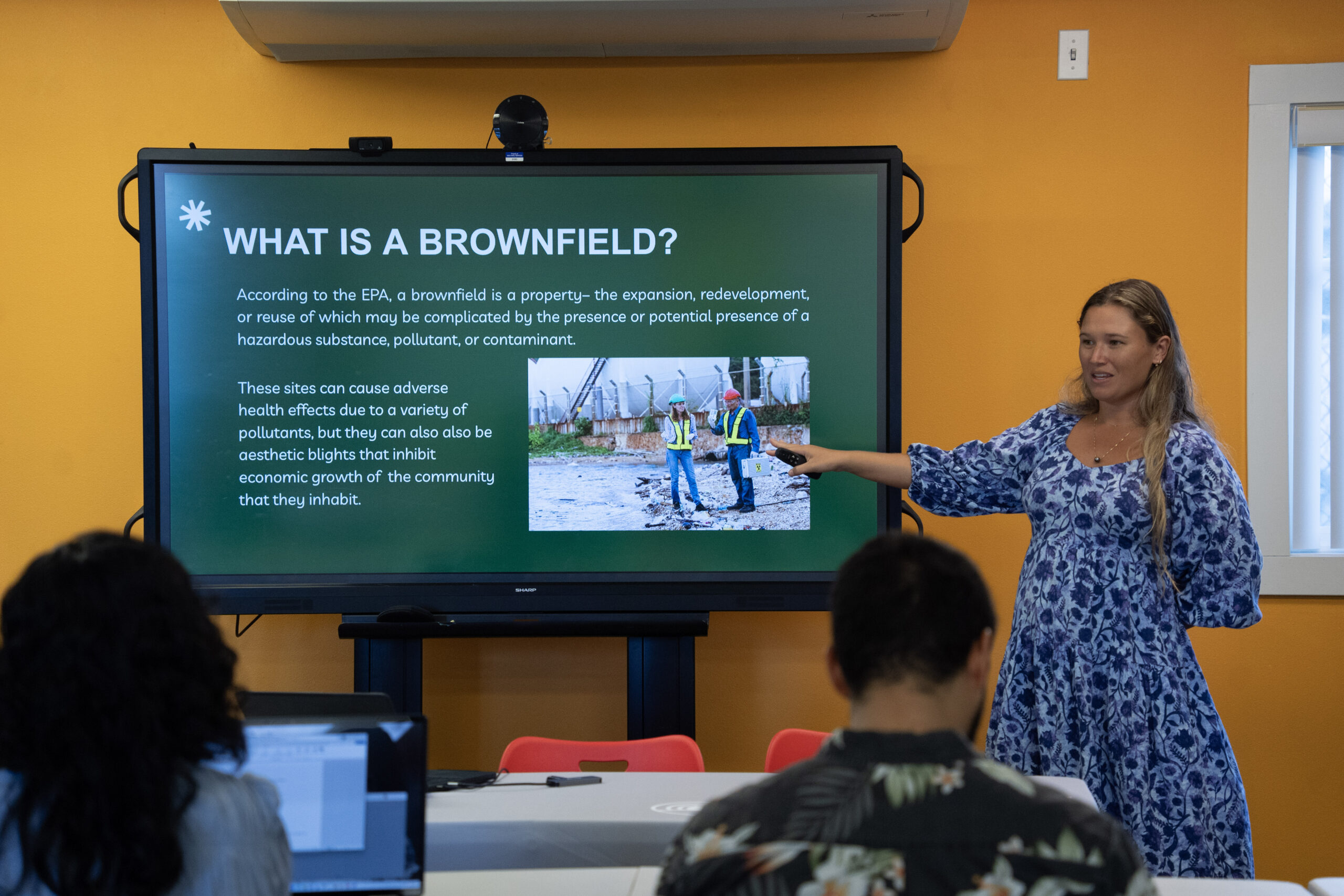

Places like these are known as brownfields — properties that have gone unused and potentially hold contaminants that would complicate public uses. They can include abandoned gas stations, old buildings, former industrial sites, fallow sugar cane lands once sprayed with pesticides, or lots burned down in the 2023 Lahaina fire.

Two Maui organizations are trying to find properties like these, with the goal of working with landowners and communities to identify sites important to the public and test them for environmental hazards. The hope is they can be cleaned up and turned into public spaces.

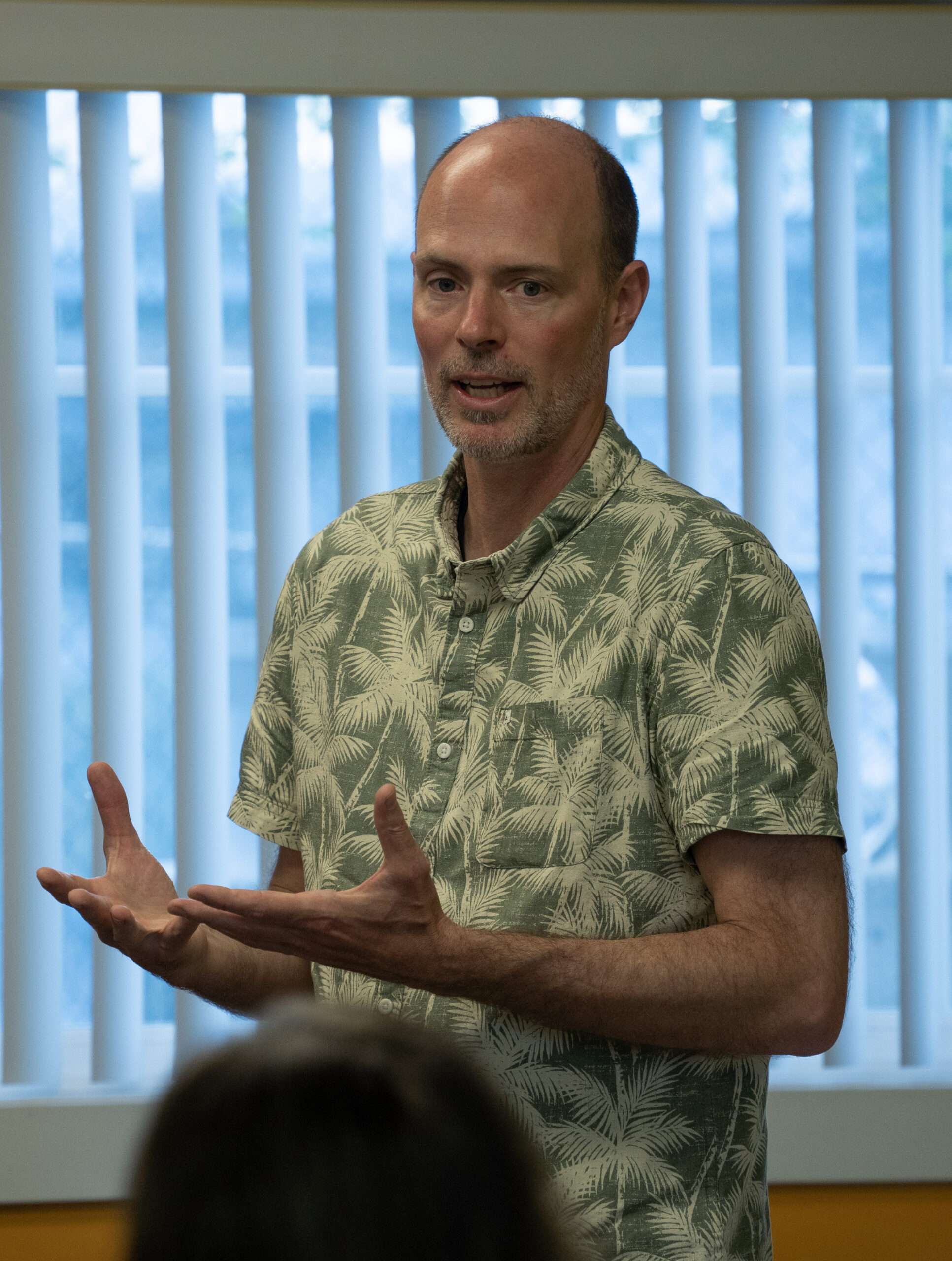

The Environmental Recovery Initiative, spearheaded by the nonprofit Maui United Way and the consulting firm Hā Sustainability, is focused on more than 30 sites in Central and West Maui compiled primarily from databases of the state Department of Health and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, according to Alex de Roode, co-founder and principal of Hā Sustainability and former Maui County energy commissioner.

Thousands of people live in these areas, and many of the brownfields are in central locations.

“It’s a public health and environmental risk,” Hannah Shipman-Peila, co-founder and principal of Hā Sustainability, said during a public workshop in Kahului on Wednesday. “… If we could turn that into something, whether it’s affordable housing, a commercial space, a park or a place where nonprofits could have space … it adds value to that community.”

Not every abandoned or unused site may be hazardous, however. The state Department of Health said in an email to the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative that “in most cases, these sites do not pose an immediate threat to residents or surrounding neighborhoods. The concern is typically about the potential presence of contaminants, not ongoing exposure.”

Before a brownfield can be reused, it should undergo an environmental assessment to see if it poses a health risk, the department said.

In Central Maui, examples of unused lands the project is focusing on include an old Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Co. facility on Camp 5 road in Kahului, a former gas station across the street from the University of Hawai‘i Maui College, and dilapidated vacant buildings on Market and Main streets in Wailuku.

In West Maui, potential brownfields include the Olowalu temporary fire debris disposal site, old Pioneer Mill facilities, and several structures in the burn zone that once served the public, such as Ka Hale A Ke Ola’s former homeless shelter and historic Waiola Church.

De Roode and Shipman-Peila said the goal is to narrow down 10 priority sites and then consult with landowners. The sites flagged for testing would have to be places agreed upon by the community and landowners.

“We would engage with the landowner and say, ‘This is what the community’s expressed to us. How do you feel about it? Are you interested?’” de Roode explained. “And if they say, ‘No, you know, that’s really not the direction you want to go,’ then it’s probably not a good site for this project. We would move on to other sites.”

Maui United Way has a $500,000 grant from the EPA for the two-year project, with over half of it going toward environmental testing. Additional funding would have to be secured for cleanup and any future uses.

Over the past two decades, the EPA has provided more than $22.7 million for the cleanup and reuse of underused properties in Hawai‘i, the agency said in 2022.

One example of a brownfield-turned-public project was the 100-unit Nohona Hale, an affordable housing complex in Honolulu that was built on the site of a former parking lot with oil and gasoline drum storage. Federal funds covered the environmental studies and the state and private developers built the project that was completed in 2020.

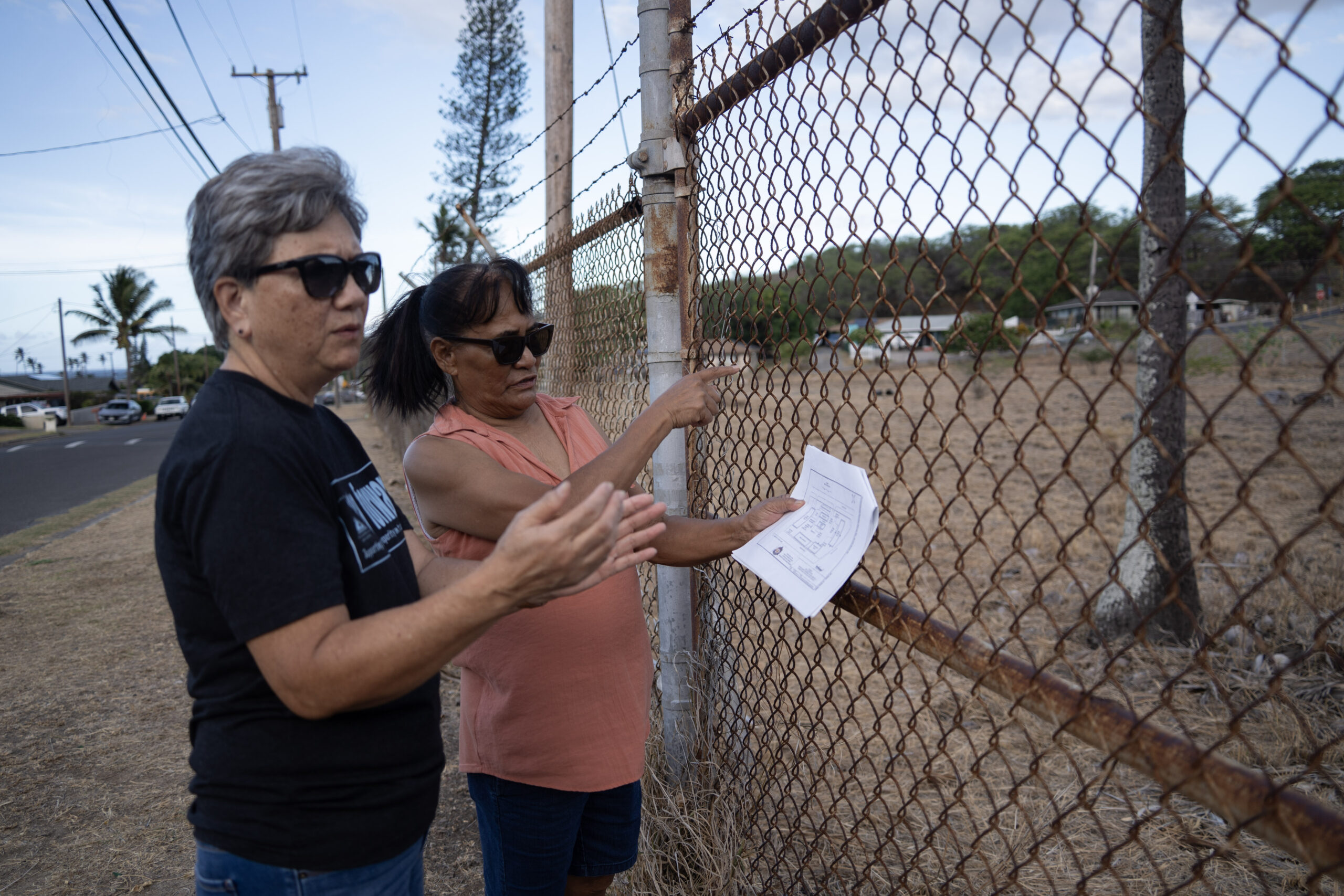

In Paukūkalo, the former National Guard armory is a prime example of a site that the community is eager to see put to good use.

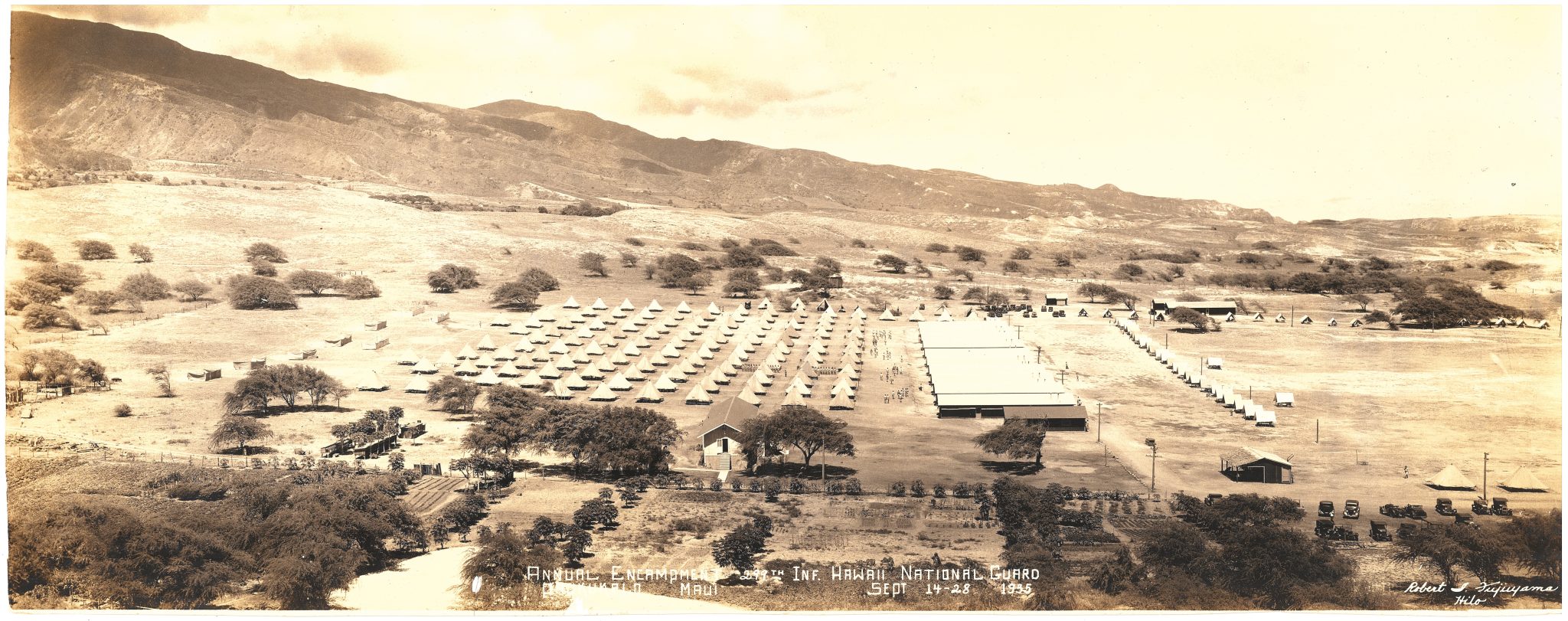

The military had a presence in the area for decades, and the armory was part of a larger site called Camp Paukūkalo that operated from about the late 1920s through 1962, according to a 2005 report obtained by members of the Paukūkalo Hawaiian Homes Community Association through a Freedom of Information Act request and shared with the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative. The camp had a training areas and rifle range used by the Hawai‘i Army National Guard and the U.S. Navy during World War II.

In 1962, the National Guard transferred a large portion of Camp Paukūkalo to the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands. The only remaining property owned by the National Guard was the armory, which included a maintenance shop, a fueling station, vehicle storage areas and a wash pad. In August 2004, armory operations moved to Pu‘unēnē, and the property has been unoccupied ever since.

Residents say they don’t know what’s left at the site. Diagrams show there was once a gas pump connected to a 2,500-gallon underground storage tank as well as a 1,000-gallon aboveground storage tank. The underground tank was operational from December 1942 to May 1997. When it was decommissioned, it was found to be intact, with no soil staining or odors, the 2005 report said.

But soil tests showed the areas under the fuel dispensers were the most heavily impacted and exceeded state action levels. After a second excavation found additional soil samples were “well below” state action levels and the excavated sites were filled in with clean soil, the Department of Health said no further action was needed.

The site also stored hazardous materials like solvents, petroleum, oil, lubricants and paint, and the 2005 report cautioned that while it’s unlikely, there could even be small caliber blanks in the soil from past training exercises.

Sing-Keliikoa, a 1989 Baldwin High School graduate, wants to see it become a place where the community can farm and gather, but only after it’s been tested again, because she’s concerned about what still might be underground.

She served in the National Guard from 2000 to 2014, primarily on O‘ahu as a petroleum supply specialist, and she’s also an environmental engineer who was sent to different military sites over the years to assess hazardous spills. She said she’s only set foot on the former armory once with her father, who served in the National Guard.

“It’s always been a sore spot in my heart because it’s so close, yet we can’t use it,” she said. “But I wouldn’t use it unless it was definitely a safer place for our community.”

Janice Herrick, treasurer and board member of the Paukūkalo Hawaiian Homes Community Association, said residents have been trying for years to get the state to do something with the site. At a Native Hawaiian Convention in 2024, then-U.S. Treasurer Marilynn Malerba suggested they try the EPA’s Brownfields Program.

But the process seemed “really complicated,” and soil testing was expensive, Herrick said. So when she learned there was a project geared toward helping communities assess contaminated sites, she was thrilled. Paukūkalo has limited land, and Herrick said developing the site would make use of precious space and bring the community together again.

“I think this will be a huge thing for the community to feel like they’re part of something,” Herrick said.

Gracey Gomes, a fellow board member who’s lived directly across from the old armory since she moved to Paukūkalo in 1999, said having a military facility in their residential neighborhood was just an “accepted” fact of life. Her grandfather served in the National Guard and worked at the armory.

But now that it’s empty, she and Herrick envision so much potential — walking paths for kūpuna, space for native plants and food trees like ‘ulu, hydroponics, a community center for events and meetings — anything to create income, provide food security or foster a sense of community.

“Now with this brownfields (project) coming up, it’s like a gift in disguise for us,” she said. “Maika‘i. I love it.”

The Department of Hawaiian Home Lands did not immediately respond to a question about why the site has remained empty for so long.

As Central Maui residents dream up plans for long-abandoned sites, Lahaina residents are thinking about what they want to see in their town.

In Lahaina, many brownfields targeted by the project are parcels burned in the 2023 wildfire or created in the aftermath, such as the temporary disposal site set up at the Olowalu Landfill to handle fire debris. As of Friday, about 80% of the 400,000 tons of debris had been moved to the permanent disposal site at the Central Maui Landfill. The plan is to eventually close the facility, though its future use hasn’t been decided yet and will be discussed at an open house on Sept. 20.

Another brownfield is the 42 acres of county-owned land in Ukumehame and Olowalu near mile marker 13.5. In August, seven people were arrested while trying to stop the county from forcing the houseless community out of the area over wildfire risks.

Anuhea Yagi, who lived in Lahaina for over 20 years and moved to Wailuku shortly before the fire, said it’s a critical portal between Central and West Maui and that it should be a priority to find a solution for both unhoused residents and “such an ecologically sensitive space.” Maybe, she said, the land could be restored and made into a safe place for people to live.

She also suggested creating a resource hub where people could shelter during a fire or use the bathroom.

“I think what was proven in the fire is a resilience hub can happen anywhere,” she said during a brownfields workshop in Lahaina on Thursday. “It happens in the moment and the space that it’s needed. … The resilience is us.”

Another brownfield whose future is up in the air is the former site of King Kamehameha III Elementary School, which burned down in the fire. The state Department of Education has said it can’t rebuild the school on the same site because of the ‘iwi kupuna (ancestral remains) found during debris removal. Residents want to see the site preserved and cared for.

Lena Granillo, a senior at Lahainaluna High School, said she remembered her kumu at King Kamehameha III Elementary taking the students to old burial sites near the banyan tree.

“He had us there for like an hour and a half just telling us about everything and about how important it is to remember and keep the history and not let it like wash out and die,” Granillo said.

She doesn’t want the ‘iwi kupuna to be forgotten or disturbed, and wants to see the space preserved, drawing agreement from other residents.

“We want our wahi panas (sacred spaces) to be able to stay intact,” Primrose Lehualani Harris said.

For Harris, another concern is the land mauka of the Villages of Leiali‘i subdivision where she lives. It is former agricultural land filled with leftover black tarps and old pipes. She worries about what’s in the land. Since the community is already working to replant the area, she thinks it makes sense to test the soil.

As for the future of other brownfields that burned down, she said every property is different.

“There are certain places that people do need to get back into, so I do hope for them that they’re able to get back,” she said, adding that other places may need a different vision.

De Roode said for landowners in Lahaina who want to build what they had before, the funding could help with environmental assessments if the facility benefits the public.

Jeeyun Lee, interim CEO of Maui United Way, said the Central and West Maui sites offer different opportunities. In Kahului and Wailuku, there’s a chance to “enhance what’s already existing,” such as adding more housing. In Lahaina, it’s about building trust and ensuring public safety as the community recovers.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers conducted soil sampling as it cleared burned properties in Lahaina and Upcountry, and Lee said it will be up to the community to say whether they want more testing two years after the disaster.

“This actually provides the opportunity to not just kind of level set, but to really move intentionally towards the spaces that we really want to prioritize as a community,” Lee said.

The spaces could be made even more accessible and useful to the community at large, Lee added.

Since the fires, the health and safety of Lahaina continues to be studied. The University of Hawai‘i’s Wildfire Exposure Study recently reported that participants were showing signs of diminished lung function likely tied to “prolonged wildfire smoke exposure and persistent environmental contaminants.”

But the Department of Health, which monitors air quality, coastal water quality and other environmental factors, maintains that since the removal of debris, overall the area “is safe from fire-related environmental concerns for residents and workers.”

“Thousands of environmental samples collected by DOH and other agencies responding to the Maui wildfires show that there is no ongoing environmental exposure threat associated with living or working in the impacted area in Lahaina,” the department said.

A benefit of Maui United Way’s EPA grant is that it includes the creation of an area-wide plan for Lahaina, which would look “beyond a single brownfield site and addresses how the cleanup and reuse of brownfields can support broader neighborhood revitalization.”

Workshops were held this week in Kahului and Lahaina to start identifying priority sites. The next steps will be talking to public and private landowners, with environmental site assessments slated for winter and spring of next year, and concepts for potential uses developed in summer 2026. The final findings will be submitted in fall 2026.