Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative

Hawai‘i Journalism InitiativeOn-demand ride service could replace least-popular Maui Bus routes

Two Central and Upcountry Maui Bus routes with the lowest ridership in the system could be replaced by an on-demand, flexible ride service that works like a hybrid between Uber and a public bus with the same public bus rates.

“Microtransit” is an alternative form of transportation that would allow people to request trips by phone or smartphone app within a specific zone and share a ride with other people traveling in the same general direction.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

Peter Soderberg, associate principal with Nelson Nygaard Consulting Associates, which is helping the county develop a microtransit plan, said the service is suited to smaller, less-dense communities.

“Transit is not a one-size-fits-all approach,” Soderberg said during a virtual meeting on Wednesday. “As we get down the line to lower and lower densities, we start seeing the most effective transit modes start to shift a little bit away from larger, more frequent buses … down to some smaller, more shared services like microtransit.”

Maui County is looking into the service for the Waihe‘e Villager route and the Kula Islander route, which are the bottom two in ridership of the 12 fixed routes in the Maui Bus system.

Instead of a bus, a smaller vehicle would be stationed in each zone covered by these routes and be available to pick up riders in about 10 to 20 minutes on average, Soderberg said. The program’s software would create a route and itinerary based on ride requests in the area and send it to both the driver as well as the passengers so they can know how long to expect the ride to take.

The plans for microtransit came out of a 2022 study about the Maui Bus, which serves around 2 million people a year in West, Central, South and Upcountry Maui.

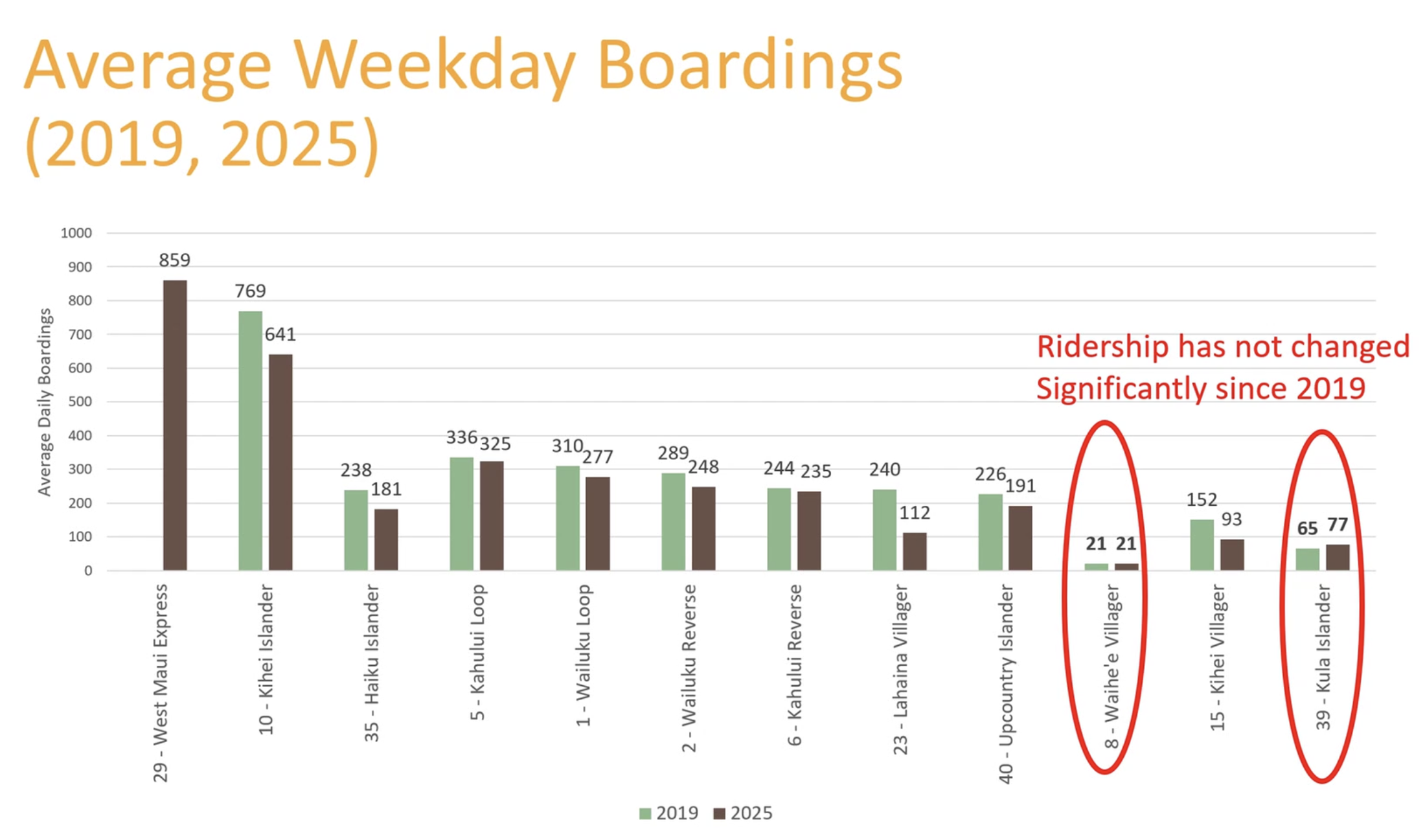

The study showed that the Waihe‘e Villager and Kula Islander were the least-ridden routes at the time, and that was still the case in 2025, Soderberg said.

The Kula Islander currently averages about 77 boardings per day at a rate of 4.9 boardings per hour, while the Waihe‘e Villager averages about 21 boardings per day with about 1.6 boardings per hour.

At fewer than five boardings per hour, alternative services like microtransit “start to make more sense,” Soderberg said.

By comparison, the most popular Maui Bus routes — the West Maui Express and the Kīhei Islander — each see more than 600 average daily boardings.

Both the Waihe‘e Villager and the Kula Islander are challenging for riders to catch because they only come once every three hours, and both tend to run late nearly 40% of the time, according to the 2022 study. Miss one of these buses, and you’ll be waiting a long time for the next one, Soderberg said.

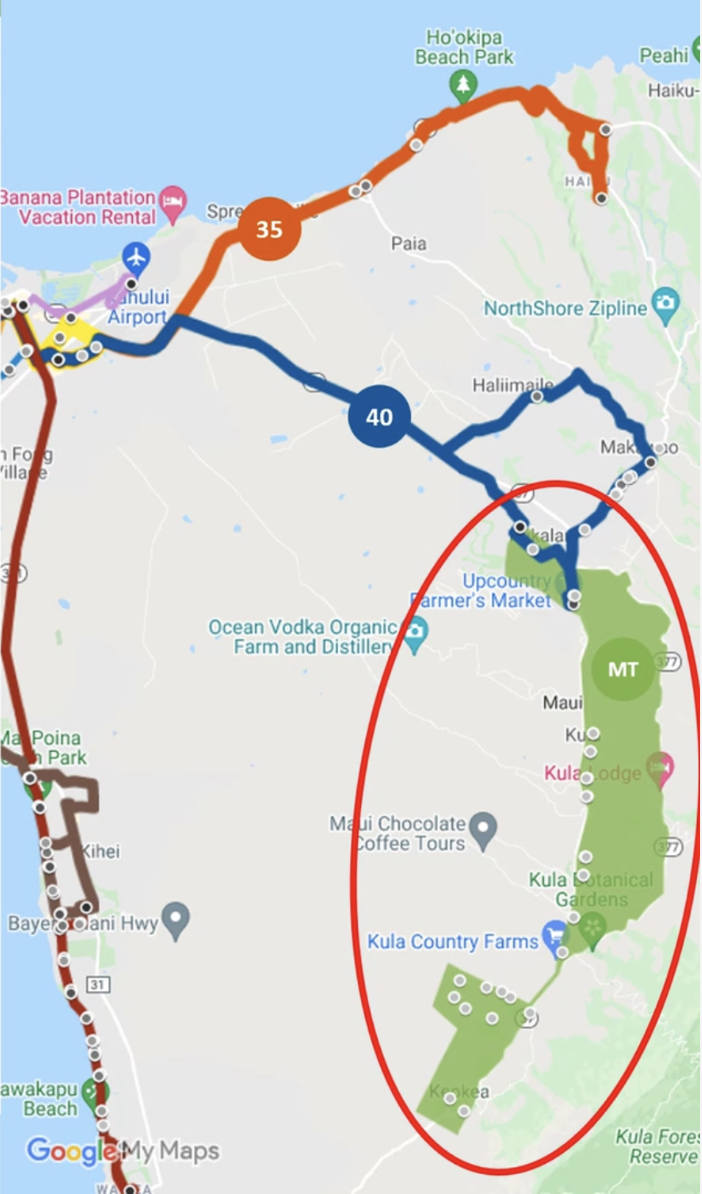

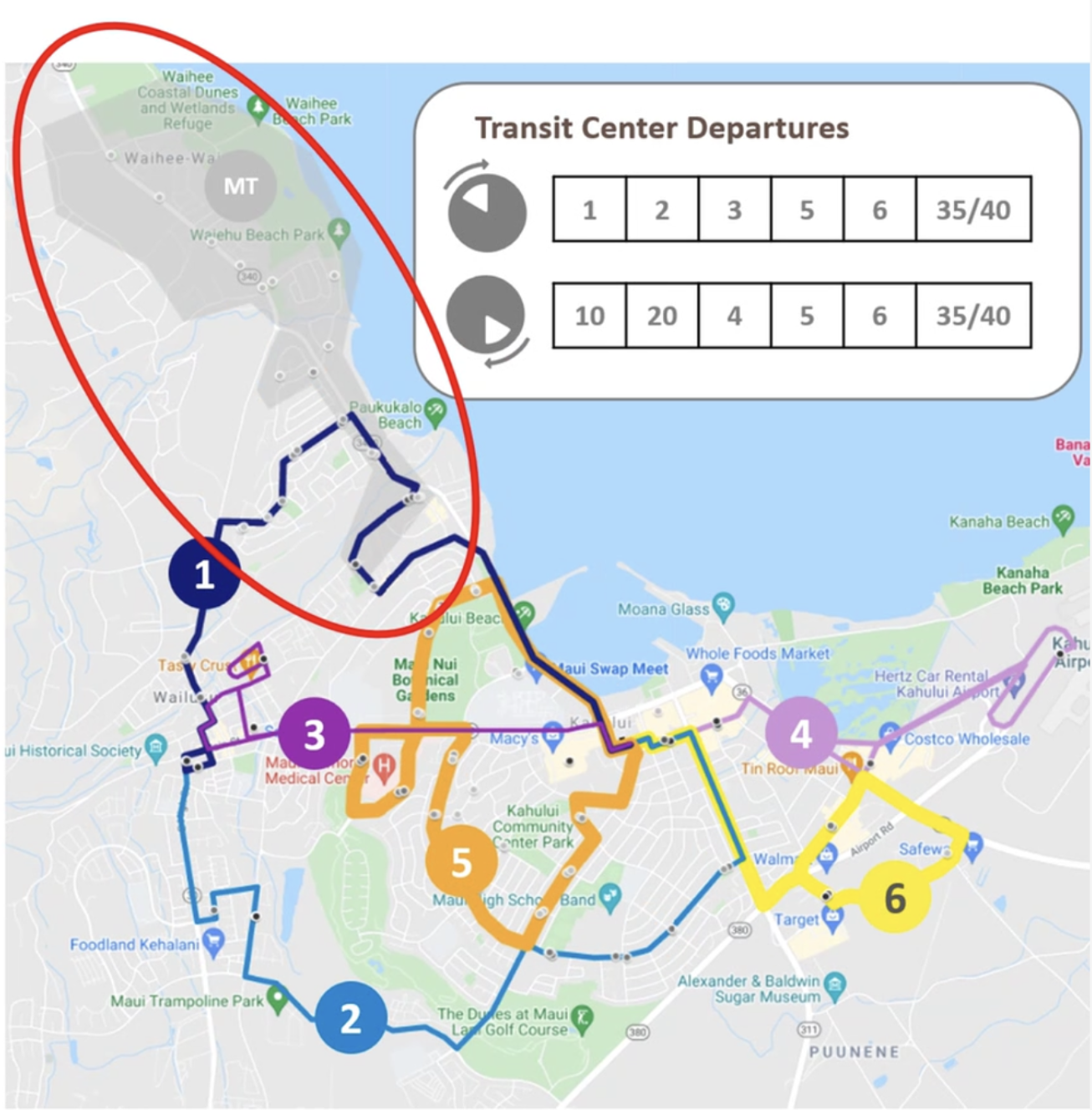

The idea is to replace the two fixed routes with a zone that encompasses the current bus stops in both areas. In Waihe‘e, the zone would range from Kahului Harbor to the Waihe‘e Coastal Dunes, with a direct connection to the Kahului Transit Center, where riders can access the rest of the bus network. In Kula, the zone would stretch from Pukalani to Kēōkea and require a transfer to get to the Kahului Transit Center.

In Kula, with its tight, winding roads and steep hills, a smaller vehicle could help improve access to public transit, Soderberg said. He added that they’re considering whether to have the service pick up riders in their specific locations or at designated stops.

The microtransit ride service would have the same pricing structure as the bus, though Soderberg said the current study is focused on designing the service logistics, not the rates. Current Maui Bus fares are $2 one way for all fixed routes, commuter and ADA paratransit services, with free fares offered to certain riders, such as children, students, seniors and residents with ADA paratransit ID cards. Daily passes cost $4, while monthly passes are $45.

Darren Konno, transportation program coordinator with the Maui County Department of Transportation, said that the funding for microtransit will come from the county highways fund. The purchase of a microtransit vehicle will be federally funded with a 20% match by the county.

Soderberg said the goal is to make the changes cost neutral, with the plan recommending that microtransit doesn’t significantly cost more than a fixed-route bus.

The annual cost to operate the Maui Bus’ fixed routes was nearly $8.1 million, according to the 2022 study, at a rate of $94 per hour for 86,000 hours of contracted fixed-route service.

Microtransit is expected to require 10,000 hours at a lower rate of $87 per hour, and with the plans to include redesign of the current bus system with a projected decrease in fixed-route hours of 3,000, the new total cost would be about $8.6 million.

Maui County Council Member Yuki Lei Sugimura, who lives Upcountry, said microtransit could work in her community, where the Kula Islander often travels down her street with one or two passengers or none at all.

But Sugimura said there is still a need for public transportation for senior citizens and other people trying to get to Central Maui. She said microtransit could help determine the actual need.

“It’ll probably be more realistic in terms of needs and uses, rather than just an automatic route that goes regardless if you have one passenger,” said Sugimura, who also sits on the Maui Metropolitan Planning Organization’s Policy Board.

Some residents who live and work far away from bus stations say they would also like to see microtransit in their area.

Natalia Barboza is a case manager with The Maui Farm, which offers farm-based, family-centered programs in Makawao. The farm is located just off Baldwin Avenue, not far from other social service providers, including Maui Youth and Family Services and the Hawai‘i Job Corps Center. To get to the nearest bus station, families and employees have to walk an hour to either Pā‘ia or Hāli‘imaile.

“So you have a lot of underserved populations up here who are probably really trying to focus on getting to work, to appointments, and (the bus) is not a nearby option,” Barboza said.

Barboza said having an affordable ride service in the area would help residents who sometimes pay $50 to $70 a day to get an Uber to their job or just another bus stop. Spending that much for daily transportation makes it harder to save up for a car of their own.

“Not everybody can afford a vehicle and insurance and the gas prices right now,” Barboza said. “There’s a lot of hardship since COVID, the fires.”

Nick Nikhilananda, who lives in Huelo and attended the meeting on Wednesday, said microtransit would also be useful in his area because of the distance between homes and the nearest bus stop. He doesn’t use the bus because he would have to drive to the Ha‘ikū Community Center, and the bus doesn’t have the flexibility he needs when running errands.

When he ran for the council in 1998, Nikhilananda said he was a big proponent of public transportation and “spoke passionately about how we need it for young people and seniors.” But he knows the fixed-route system doesn’t work for everybody.

As the son of a World War II veteran who was a triple amputee, Nikhilananda said he knows what it’s like for someone to be in a wheelchair or unable to walk several blocks.

“I totally support the concept of microtransit from the environmental, from the accessibility, from the cost, all those levels,” he said.

Soderberg said other areas could also be considered for microtransit in the future.

Consultants also are looking at different microtransit services, including Seattle’s Metro Flex, Northern California’s Ride Plus, Los Angeles County’s Metro Micro and Louisiana’s Capital Area Transit System. Some of the things that seem to work best in these systems include advanced booking options, multiple booking options such as an app or call line, wait times of 10 to 20 minutes and fares that are aligned with fixed-route bus service.

The community outreach process has just started this month. There will be more chances for public input as the service is designed from now until March and as recommendations and a report are developed from April to June.

“It’s really important for us to engage with community members and the stakeholders throughout this project,” Soderberg said, “so we get your perspective on what matters to you and what is an important component of this service to make sure it’s useful for you and can actually help you complete your trips that you’re making today, if not at the same level, in an improved way.”