Study: Nearly all forest birds can spread deadly avian malaria

Nearly every forest bird species in Hawaiʻi carries and transmits avian malaria, according to a University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa study explaining why the disease persists wherever mosquitoes are found.

The research, published Tuesday in Nature Communications, identified the parasite at 63 of 64 test sites across the state. The disease is the main reason native honeycreepers are disappearing, including the ʻiʻiwi, or scarlet honeycreeper, and the ʻakikiki, which is now extinct in the wild, researchers said.

“When so many bird species can quietly sustain transmission, it narrows the options for protecting native birds and makes mosquito control not just helpful, but essential,” said Christa Seidl, mosquito research and control coordinator for the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project.

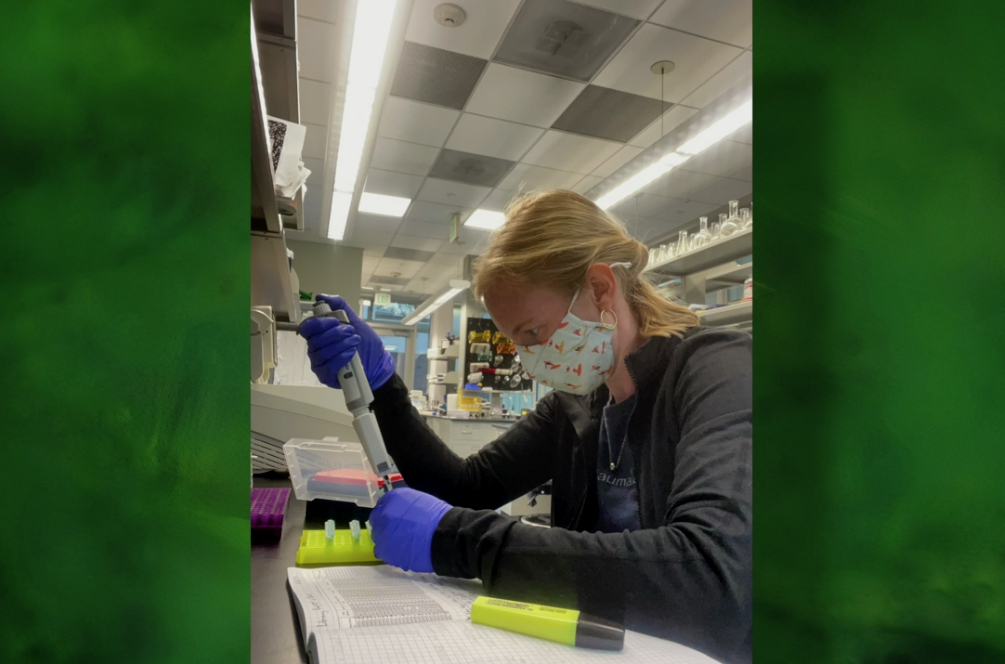

Scientists analyzed blood samples from more than 4,000 birds on Maui, Kauaʻi, Oʻahu and Hawaiʻi Island. They found that both native and non-native birds are at least moderately capable to infecting southern house mosquitos — the avian malaria’s primary vector — with the Plasmodium relictum parasite.

For a native ʻiʻiwi, the infection is fatal 90% of the time, according to the study. A single mosquito bite in a Maui backyard or Upcountry forest can lead to organ failure and the death of an entire flock.

The study also found that birds with very low levels of the parasite still pass the disease to mosquitoes. Because individual birds can harbor these infections for years, they act as reservoirs for the disease in the wild.

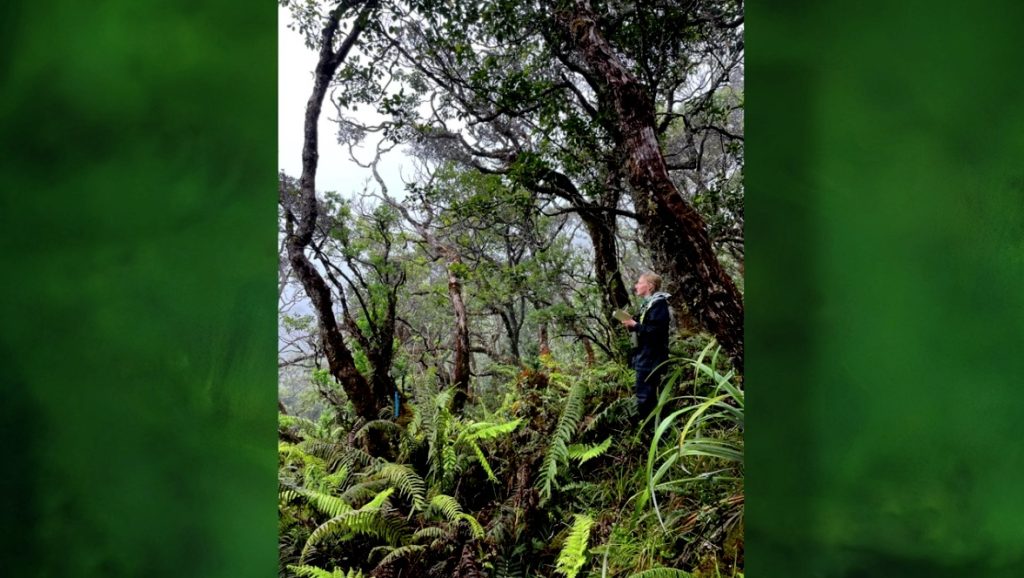

Warming temperatures are making the situation worse by shrinking “mosquito-free” zones in high-elevation forests. As these cool-weather refuges disappear, native birds have no place left to escape from the southern house mosquito.

The findings confirm the urgency of the Birds, Not Mosquitoes partnership, which is working on mosquito control to prevent the total extinction of the state’s remaining endemic birds, Seidl said.

The Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project is with the Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit at the University of Hawaiʻi.