UH solar eclipse research finds turbulent structures in the Sun’s corona

Researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi have uncovered new clues about how energy moves through the Sun’s outer atmosphere, using one of nature’s rarest events as their window: total solar eclipses.

Drawing on more than a decade of eclipse observations, a team led by Shadia Habbal at the Institute for Astronomy has, for the first time, clearly identified turbulent structures in the Sun’s corona and shown that they can survive far from the solar surface. The findings help explain how the solar wind forms and evolves as it streams through the solar system. The study was published in Astrophysical Journal.

“This work helps us understand how the Sun transfers energy into space,” said Habbal. “That process ultimately affects space weather, which can disrupt satellites, communications and power systems on Earth. Understanding where this turbulence comes from is key to predicting those impacts.”

Eclipse view

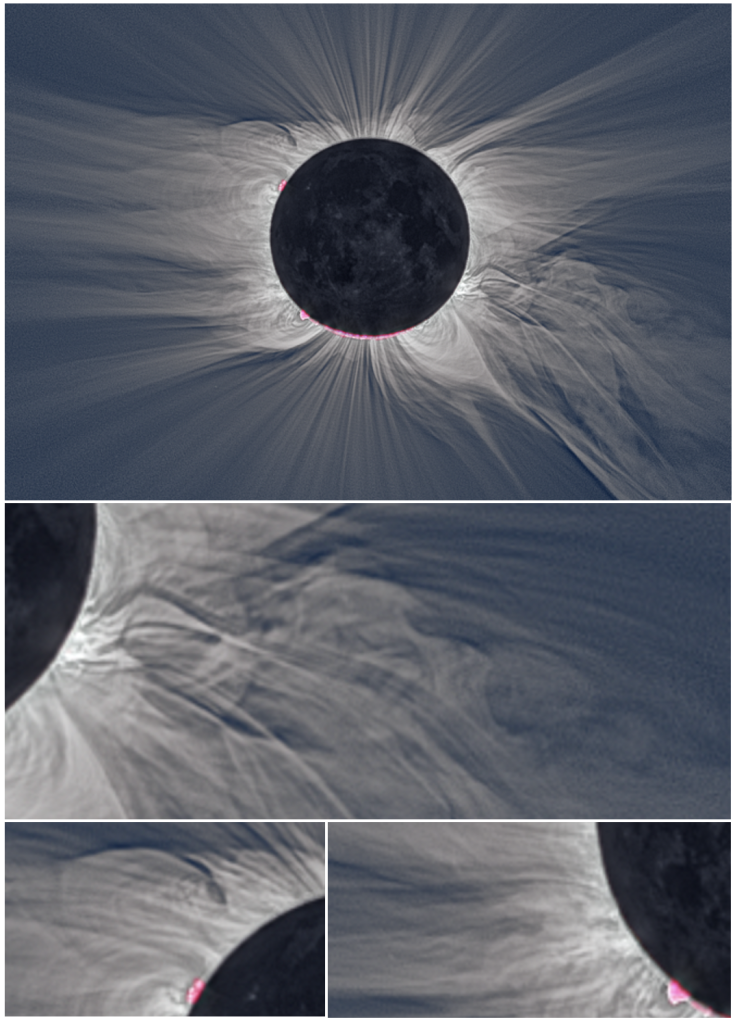

During a total solar eclipse, the Moon briefly blocks the Sun’s bright disk, allowing astronomers to observe the faint corona in exceptional detail. These moments reveal delicate, thread-like structures shaped by magnetic fields rising from below the Sun’s visible surface. High-resolution eclipse images show a corona that is far more dynamic than it appears in everyday solar observations.

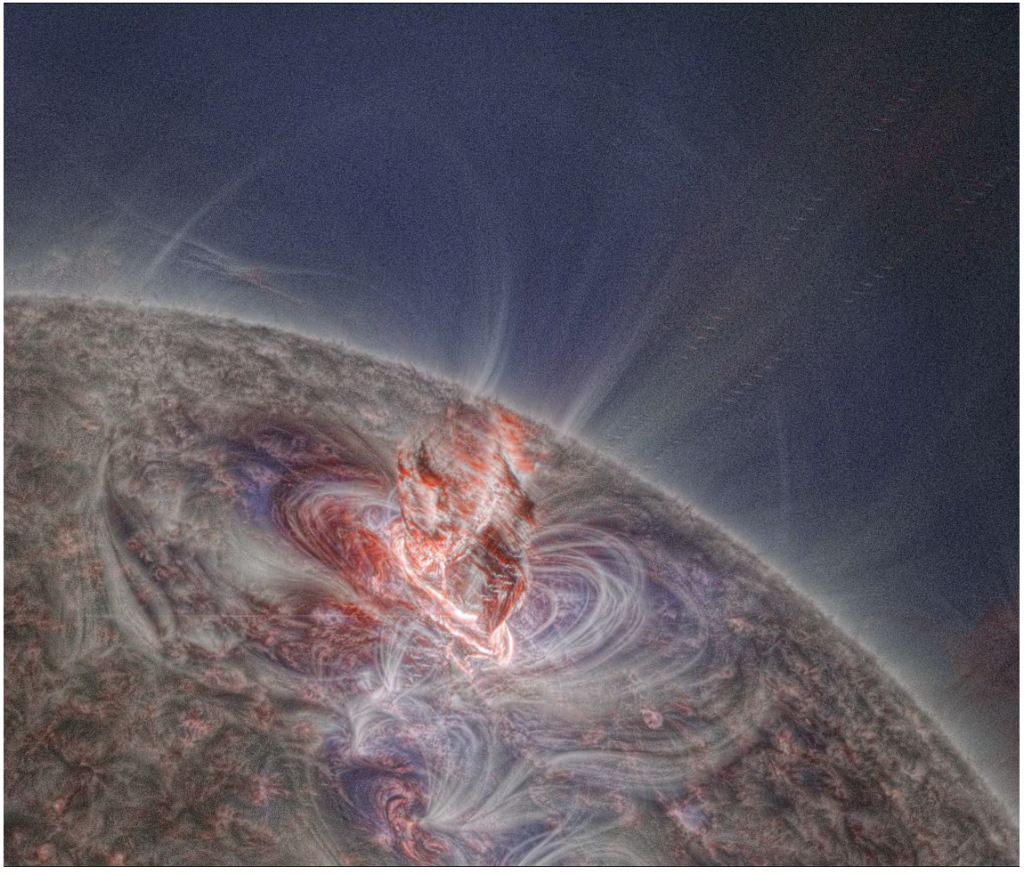

Within these structures, the team identified clear signs of turbulence. Some features form vortex rings that resemble smoke rings, while others show rolling, wave-like motions similar to those seen in Earth’s clouds. By comparing eclipse data collected over nearly 12 years, spanning a full solar cycle, the researchers traced the origin of this activity to what are called prominences—large, looping structures rooted on the Sun.

Prominences are dramatically cooler and denser than the million-degree plasma surrounding them. Where these contrasting regions meet, sharp changes in temperature and density create unstable conditions that trigger turbulent motion.

“For the first time, we were able to watch these turbulent structures form near the Sun and then follow them as they flowed outward with the solar wind,” Habbal said. “Seeing the same features later in space-based images tells us they remain intact over enormous distances.”

The study reveals the origin and evolution of turbulence in the corona, a process long linked to coronal heating and the acceleration of the solar wind.