Scent of Extinct Maui Mountain Hibiscus Revived by Science

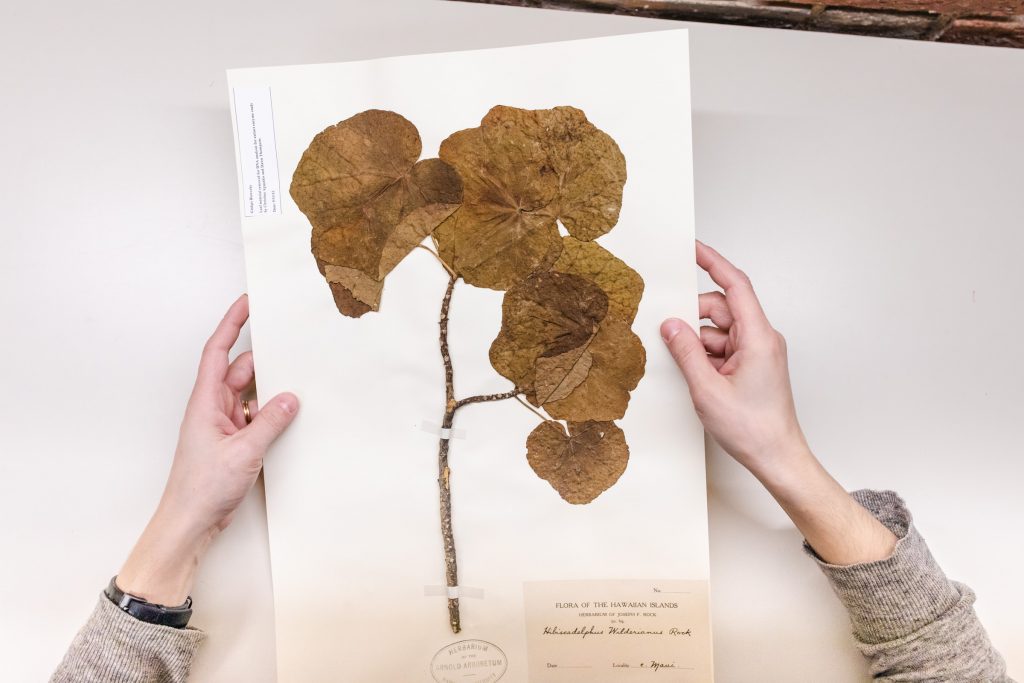

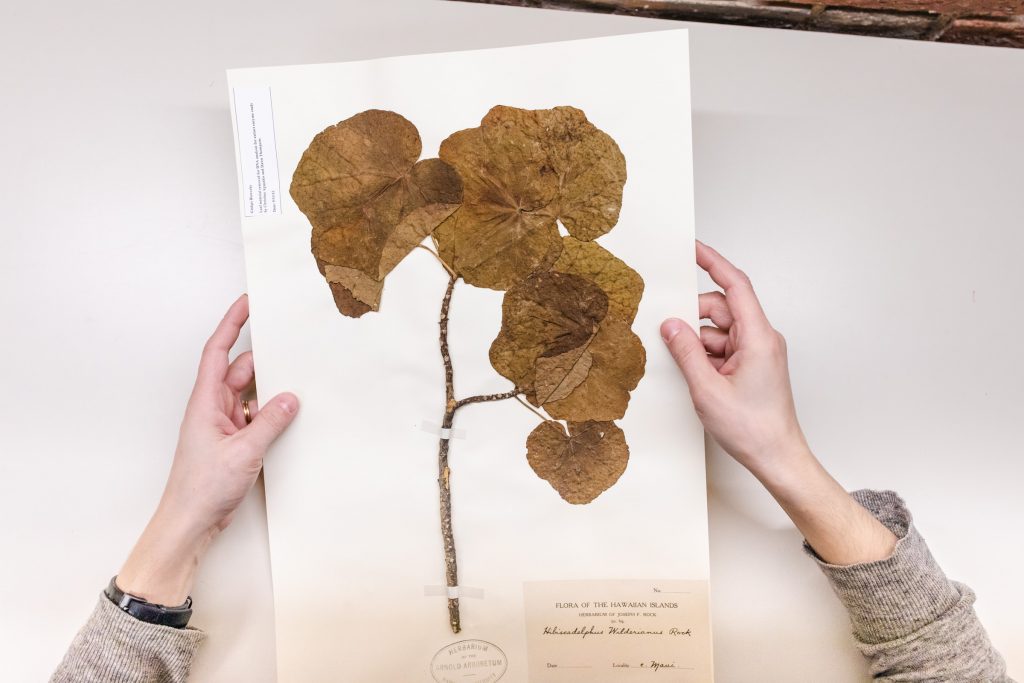

Extinct hau kuahiwi from Maui. PC: Ginkgo Bioworks

By Wendy Osher

The scent of a long extinct mountain hibiscus on Maui has been revived by science.

Everyone can point to a memory triggered by the smell of something beloved or dear to them. Now, imagine bringing back a smell that no longer exists.

That’s what scientists at Ginkgo Bioworks have done with a mountain hibiscus that is presumed to have gone extinct from the slopes of Haelakalā on Maui more than 100 years ago.

The Hau Kuahiwi was found in the ancient lava fields of Auwahi in Kahikinui on the southern slopes of Haleakalā in 1910 by horticulturist Gerrit Wilder, according to The Indigenous Trees of the Hawaiian Islands By Joseph Francis Charles Rock.

Representatives with Ginkgo Bioworks tell Maui Now, “We started with the question: could we ever again smell a flower that had gone extinct due to human activity? As biological engineers we were fascinated by the possibility of what DNA technology could do to help us experience this impossible smell.”

The last known specimen of the plant–named Hibiscadelphus wilderianus, in Wilder’s honor–was found in a dying state, covered with lichen with a single open flower and just a few developed buds. Wilder attempted to propagate the plant, and was successful in raising a single one, but realized that disappearance from its natural habitat was inevitable. “As the tree is situated on a cattle ranch, it will be only a very short time until it will have disappeared from its natural habitat,” the publication noted.

Today the species of Hau Kuahiwi that was collected is presumed extinct. The specimen was stored at Harvard all these years, until a company, which engineers smells for the cosmetic industry came across it while researching ways to bring back the scent of flowers that no longer exist.

“We searched the stacks of the Harvard University Herbarium and found several specimens of plants that had been collected more than 100 years ago, before they went extinct, including the Hibiscadelphus wilderianus, or Maui hau kuahiwi in Hawaiian, was indigenous to ancient lava fields on the southern slopes of Mount Haleakalā, on Maui, Hawaiʻi. Its forest habitat was decimated by colonial cattle ranching, and the final tree was found dying in 1912.”

Scientists with Ginkgo Bioworks made headlines in 2016, when they used a similar yeast fermentation process to produce enough flower fragrance to meet scale demands of the cosmetic industry. The GMO/synthetic biology company also engineers custom microbes for various industries, such as self-nitrogenizing bacteria for farmers and microbes that produce cannabinoids for medicinal purposes.

In this latest project, creative director Christina Agapakis recovered DNA fragments from a fingernail size sample of the species.

Representatives with Ginkgo Bioworks said, “We sampled a tiny amount of the preserved specimen of the plant and worked with the UC Santa Cruz Paleogenomics lab to extract and sequence its DNA, finding genes that could have been involved in producing fragrant molecules. We took those gene sequences and inserted them into yeast, bringing that tiny fragment of the plant back to life so we could measure what molecules it might have made. We then collaborated with renowned smell researcher and artist Sissel Tolaas, sending her that list of smell molecules we found in the yeast, which Sissel (supported by IFF, inc) then sourced from around the world and composed into the resurrected smells.”

Once dependent on the Maui honeycreeper for pollination, the smell of the plant was brought back to life by “refashioning the material into a working gene” and placing it into yeast, which “served as a living host.” That process reportedly produced fragrant compounds. The finding was published in the February edition of Scientific American in an article by Rowan Jacobsen.

The resulting artwork from the study, created in collaboration with multidisciplinary artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, is titled “Resurrecting the Sublime” and is going to be shown at the Centre Pompidou in a show about biotechnology and art that is opening this week.

“In the museum installation by Daisy, fragments of each flower’s smell diffuse and mix, introducing contingency: there is no exact smell. The lost landscape is reduced to its geology and the flower’s smell: the human connects the two, and in contrast to a natural history museum, the human becomes the specimen on view,” representatives with Ginkgo Bioworks said.

Researchers from the organism design company tell Scientific American that they are hopeful that the scent will not only get people to “think about what’s been lost;” but also help researchers in “determining how extinct species functioned.” The Maui mountain hibiscus is the company’s first “resurrected fragrance.”

Company representatives tell Maui Now, “For a plant like this that was lost due to human activity, being able to use this kind of DNA technology to again experience a small part of it and remember something we could never experience and feel in a way the tragedy of extinction, we hope that it will help encourage conservation and new approaches to considering the future of nature and technology.”

So what does the extinct hau kuahiwi smell like? Descriptions in Scientific American have ranged from “lightness” to “ethereal.”

Extinct hau kuahiwi from Maui. PC: Ginkgo Bioworks

Extinct hau kuahiwi from Maui. PC: Ginkgo Bioworks

Extinct hau kuahiwi from Maui was archived at Harvard for 100 years. PC: Ginkgo Bioworks

_1768613517521.webp)