New seabird restoration project highlights connection between culture and conservation

A seabird restoration project was initiated this week at Nuʻalolo Kai on the rugged and remote Nā Pali coast of Kauaʻi. The project is a partnership of multiple organizations and aims to restore seabird populations that have been lost from the site due to introduced predators.

“Nuʻalolo Kai is one of the most important cultural sites on Kauaʻi and was occupied for over 800 years from the 12th to the 20th centuries as a vibrant Hawaiian fishing village,” organizers said.

The site has been the focus of a dedicated cultural restoration project by the Nā Pali Coast ʻOhana and Hawaiʻi State Parks Archaeology Program. Damaged archaeological features have been restored, and native and Polynesian plants re-established.

“The seabird project is an important next step to restoring the site to what it used to be,” said Kumu Sabra Kauka of the Nā Pali Coast ʻOhana, “as seabirds were a vital component of the lives of people in Nuʻalolo Kai.”

Previous archaeological studies have found that seabird bones were abundant at Nuʻalolo Kai, including many seabird species no longer breeding at the site. This indicates that seabirds played an important role for the people living there, as they have throughout the Hawaiian Islands since the first arrival of Polynesians. However, introduced predators such as cats, Barn Owls and rats made their way to this remote area, resulting in the disappearance of several seabird species, according to groups protecting the site.

The Nuʻalolo Kai Seabird Restoration Project seeks to restore seabird populations through the control of introduced predators and the deployment of artificial nest boxes and sound systems to attract birds to safe areas within the site.

Funding for the project comes from US Fish and Wildlife Service, the US Coast Guard and the Army Corps of Engineers.

Priority species for the project are the endangered ‘a’o (Newell’s Shearwater), and ‘ake’ake (Band-rumped Storm-petrel), as well as the ‘ou (Bulwer’s Petrel). “Nuʻalolo Kai represents a unique opportunity to create a project that underlines the strong links between conservation and Hawaiian culture,” said Dr. André Raine, Science Director for Archipelago Research & Conservation. “With native seabirds being under threat throughout Kauaʻi by introduced predators, special sites such as these are critical for their conservation.”

The towering sheer cliff walls surrounding Nuʻalolo Kai prevent predators from easily accessing the site, and a dedicated predator control program removes those predators that enter. Since predator control was initiated at Nuʻalolo Kai by Hallux Ecosystem Restoration, the ‘ua’u kani (Wedge-tailed Shearwater) has already naturally recolonized the site, with numbers of breeding pairs growing annually.

“The seabirds are a part of the history and culture of the site and it’s great to be a part of the restoration process,” said Kimberly Shoback, project manager at Hallux Ecosystem Restoration. “It’s rewarding to see that birds are already returning since cats have been removed from the valley.”

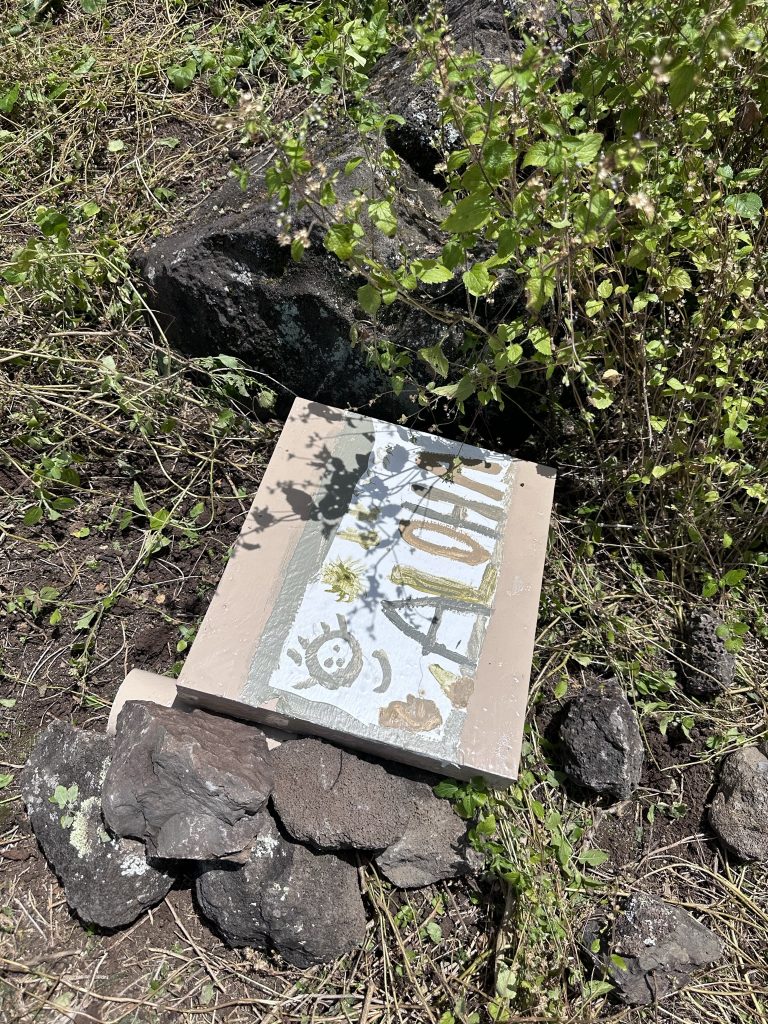

In addition to conservation, the project will also focus on an educational component. Children from Island School helped paint the nest boxes, and project partners will work on informational signage and material both on site and for tour operators.

“One of the greatest conservation threats that seabirds face is invisibility,” said Sea McKeon of American Bird Conservancy. “Most people just don’t have a chance to see and interact with these birds, despite relationships that are centuries long and deeply embedded in ocean cultures around the world. Nuʻalolo Kai is somewhere that relationship, that kinship, can be shown to visitors, while we all learn about the benefits of seabird restoration to Hawaiʻi’s ecosystems.”

All of the project partners will now eagerly be watching developments at the site this year to see how the birds respond to restoration activities. “It is a rare and rewarding privilege to contribute to a conservation project of this nature,” said Alan Carpenter, Assistant Administrator for the Hawaiʻi State Parks Division. “We are so heavily invested in managing people and creating quality recreational and cultural experiences, but there are still contributions to natural resource restoration to be made in some of the more remote and isolated corners of our parks. Restoring native bird populations in Nuʻalolo Kai is fully compatible with cultural revitalization, and we look forward to monitoring and sharing the progress.”

_1768613517521.webp)