Maui public schools included in flawed, $100 million-plus solar air-conditioning initiative

Under public and political pressure in 2016, state public schools administrators rushed to carry out a program to cool 1,000 of the state’s hottest classrooms with complex, unfamiliar and costly solar air-conditioning systems.

In his 2016 State of the State Address, Gov. David Ige told state lawmakers that he was committed to cooling 1,000 classrooms by the end of the year, calling classrooms “a sacred learning space,” but where students couldn’t learn when temperatures soared to 100-plus degrees. Lawmakers agreed to cool 1,000 classrooms with $100 million.

But it didn’t work, according to a blunt and unsparing report by the Office of the State Auditor.

Instead, the auditor found that the state Department of Education’s “Cool Classrooms Initiative” was plagued from the beginning with poor accountability, sloppy record-keeping, and significant design and installation failures.

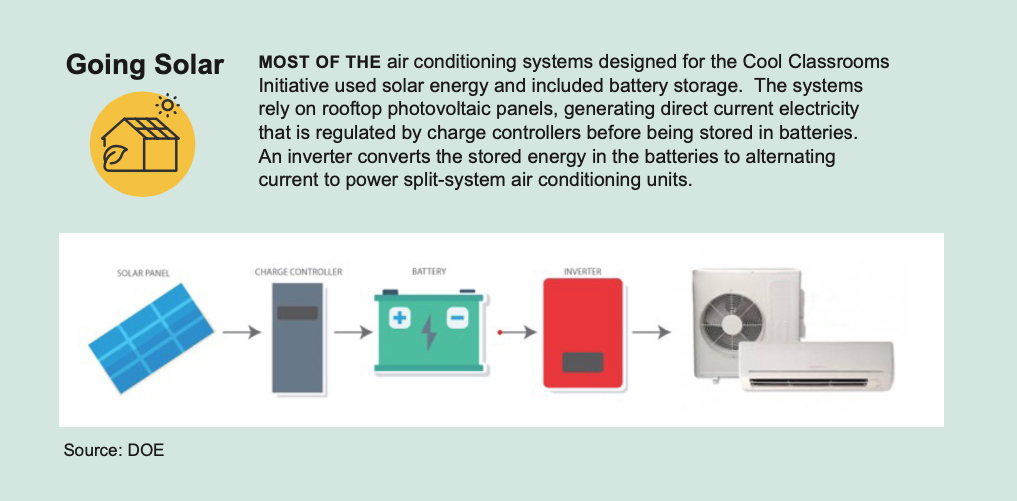

In total, $104,961,733 was spent on heat abatement at 53 schools where 838 classrooms were air-conditioned, most with solar AC systems. On average, DOE spent $125,253 to cool a classroom. From the start, many of the solar AC systems failed or didn’t work properly, resulting in a salvage effort with an estimated cost of $3.3 million to $6 million.

On Maui, the program spent more than $26 million to cool 229 classrooms, but none in hot South Maui.

“We found that rushed planning and poor decisions early on — as well as instructions not to add to the energy load — contributed to DOE moving forward with expensive and complex solar-powered air-conditioning systems (solar AC systems) that ultimately didn’t work very well,” according to the audit.

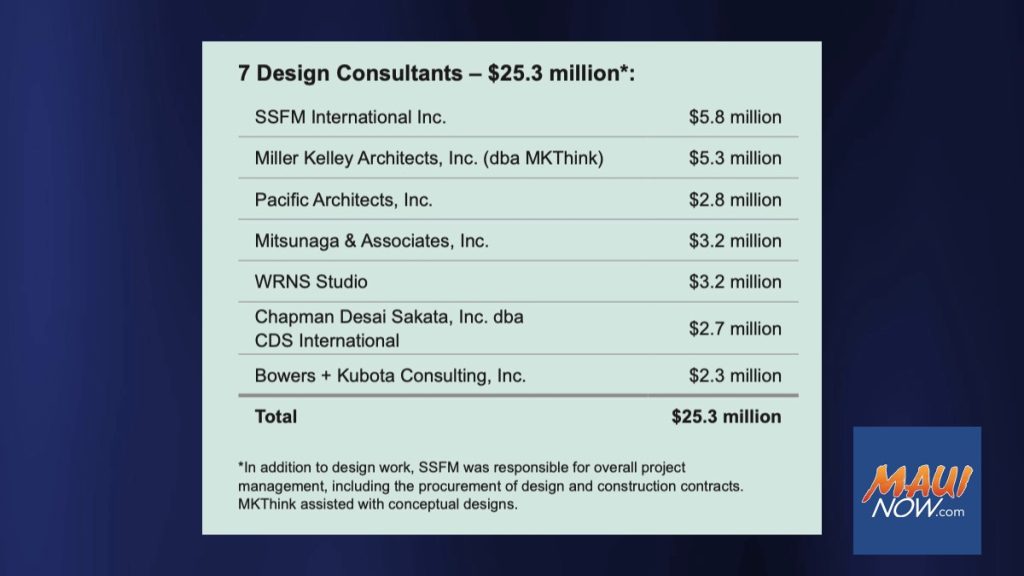

The report found that the initiative was a well-intentioned but poorly executed effort. Meanwhile, seven project consultants raked in at least $25.3 million, an average of more than $3.6 million each. The amount could be more because DOE provided the auditor “incomplete and not-100% reliable data” to account for state expenditures on the program.

Flawed project implementation

The audit detailed numerous examples of flawed implementation, including the installation of solar panels in shady areas and a lack of proper and well-informed planning.

At Castle High School on Oʻahu, for example, solar panels were installed under large monkeypod trees, which blocked sunlight and caused them to produce less than 20% of their designed power output.

The school’s head custodian, who was not consulted about the photovoltaic panels’, saw trouble ahead. “I’m not an architect or an engineer, but we figured it wasn’t going to end well,” the custodian said.

A DOE engineer quoted in the report expressed disbelief, saying: “It’s dark most of the day (under the trees’ canopies), and nobody stopped it.” The department’s former project manager called the initiative a “very rushed project” and said the trees were “missed in ‘field observations.'”

Maui schools and the cost per classroom

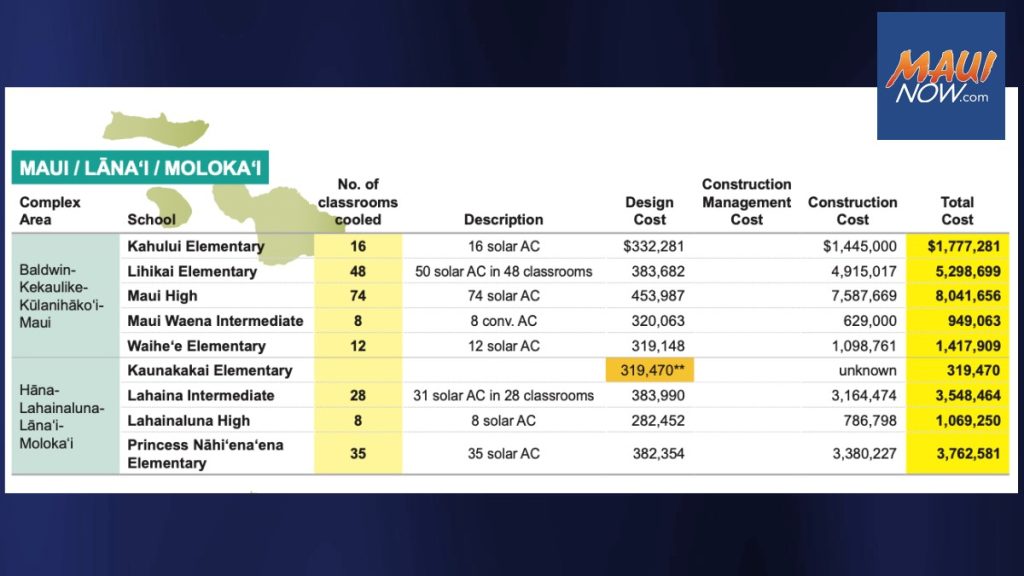

On Maui, the schools that received air conditioning were located in Central and West Maui. Kaunakakai Elementary on Moloka’i is listed, but no classrooms received air-conditioning, even though nearly $320,000 was spent for design of units.

According to the audit, 229 classrooms in Maui County were cooled at a cost of $26,184,373, an average of $114,342 per classroom. No South Maui schools were included in the program, despite Kīhei Elementary and Lokelani Intermediate classrooms being among the warmest in the state.

Maui schools listed in the audit include:

- Kahului Elementary, 16 classrooms

- Lihikai Elementary, 48 classrooms

- Maui High, 74 classrooms

- Maui Waena Intermediate, eight classrooms

- Waiheʻe Elementary, 12 classrooms

- Lahaina Intermediate, 28 classrooms

- Lahainaluna High, eight classrooms

- Princess Nāhiʻenaʻena Elementary, 35 classrooms

- Kaunakakai Elementary on Molokaʻi, with $319,470 in design costs for a project that never proceeded to construction.

A cold trail for accountability

The auditor’s mission to thoroughly and accurately assess how DOE expended $100 million in the “Cool Classrooms Initiative” was hampered by two primary obstacles:

- Public employees who had been directly involved in the program were “no longer employed by DOE.”

- DOE’s “heavy reliance on outside design and consulting firms.”

Both circumstances made it difficult for the state auditors to obtain documents, information and identify employees involved.

“In addition, DOE has not maintained copies of many documents relating to its past and current heat abatement programs; those documents remained with these consultants.”

Public reaction

Hawaiʻi State Teachers Association President Osa Tui Jr. called the solar-powered air-conditioning program a “disaster.” He said he feared it could make legislators more reluctant to fund other education initiatives.

“This only perpetuates the idea that the department is given too much money and that government is wasteful,” he said. “It’s fiascos like this that cause problems elsewhere in the system.”

Maui architect David Sellers, an expert in off-grid renewable energy, called the project “well intentioned but misguided.” He said the decentralized “nanogrid” approach, with a separate power system for each classroom, made maintenance difficult and costly.

Sellers added that the $125,000 average cost per classroom seemed high, noting that a similar system for an entire house today would be significantly cheaper. Sellers also pointed out that 30% of classrooms statewide are portable units, which are often “the cheapest, crappiest learning environment,” but cost four to five times as much as permanent buildings to operate and maintain. He said he has hope for project implementation reform with the new School Facilities Authority, which is staffed with construction and design professionals.

Marissa Kuʻuipo Baptista, president of the Hawaiʻi State Parent Teacher Student Association, said the audit “confirms what families and educators have experienced for years: extreme classroom heat disrupts learning and teaching.”

She urged state and local leaders to “act swiftly and equitably” to address the issues. “Every student, regardless of ZIP code, deserves a comfortable, climate-resilient learning environment,” she said.

Ashley Olson, a teacher at Lahainaluna High School and president of the HSTA’s Maui Chapter, said it is a “shame that such a good idea — cooler classrooms for better student outcomes — has had such an inglorious result.”

She noted that even with air conditioning, her classroom temperature is often between 80 and 84 degrees and that “you will never convince me that classrooms this hot provide an optimal learning environment.”

Department of Education’s response

In response to questions about the audit from Maui Now, Nanea Ching, communications director for the Department of Education, said the department has fully accounted for the funds, with records showing about $97 million of the $100 million appropriation was spent.

Remaining funds were either “encumbered for ongoing work or returned to the state,” she said.

Ching also said the department has put safeguards in place to prevent similar issues, including “readiness checks” before any air-conditioning project proceeds and “procurement discipline” to ensure competitive procurement is the default.

“The department recognizes that excessive heat in classrooms can make it harder for students to concentrate and for teachers to deliver effective instruction,” Ching said. “We take these impacts seriously and remain committed to improving classroom environments.”

The auditor’s report noted that while DOE Superintendent Keith Hayashi acknowledged the audit’s findings, his written response to the draft report was “unclear” and “highlight(ed) the department’s serious misunderstanding about its responsibility.”

The auditor’s response to Hayashi’s letter was direct: “Being able to account for the use of public funds is quite simply a basic, fundamental responsibility of the Department of Education.”

Auditor’s recommendations

The audit recommends that the Department of Education develop a systematic process to account for its expenditures, establish clear policies for maintaining project documents, and create a system to hold management and staff accountable. In its response to the superintendent’s letter, the auditor’s office wrote that it “hope[s] that commitment to continuous improvement includes addressing the issues that we report.”

What came next

The failed initiative was later replaced by what department officials described as “thinking outside the box” — a School Directed AC program. It offered schools department arranged and funding electrical assessments to determine whether individual schools had electrical capacity to accommodate additional power loads from AC units.

The second program was prompted, in part, because officials were getting angry phone calls from schools where the “Cool Classrooms Initiative” had either failed or was underperforming; and parents were dropping off new air-conditioning window units at schools’ curbsides because they “felt their children were suffering in the heat.”

The School Directed AC program shifted responsibility from the department to individual schools. The audit found that DOE provided the successor AC program with minimal structure and little oversight. “DOE’s knowledge and involvement in the School Directed program is ‘little to non-existent,'” the audit said.

_1768613517521.webp)