Discovery of brown dwarf companion provides new insight into stellar and planetary formation

An international team of astronomers using the combined powers of space-based and ground based observatories, including the W. M. Keck Observatory and Subaru Telescope on Maunakea, Hawaiʻi Island, have discovered a brown dwarf companion orbiting a nearby red dwarf star, providing key insight into how stars and planets form.

Located about 55 light-years from Earth, the brown dwarf companion named J1446B, was discovered orbiting the nearby M dwarf J1446. Too heavy to be a planet but too light to be a normal star, J1446B has a mass of about 60 times that of Jupiter and orbits its host star at a distance roughly 4.3 times the Earth–Sun separation, completing one orbit in about 20 years.

Remarkably, near-infrared observations revealed brightness variations of about 30%, suggesting dynamic atmospheric phenomena such as clouds or storms similar to gas giants like Jupiter but on a much larger scale.

“Studying the weather on these distant objects not only helps us to understand how their atmosphere form, but also informs our larger search for life planets beyond the solar system” said Taichi Uyama, researcher with the Astrobiology Center of Japan and lead author of the study.

The study, led by the Astrobiology Center at the National Institutes of Natural Sciences, California State University Northridge, and Johns Hopkins University is published in The Astronomical Journal.

Underestimation of stellar companions occurrence M dwarfs, or red dwarfs, are the most common type of star in our galaxy, accounting for more than half of all stars in the Milky Way.

These small, smaller and cooler than the Sun, are key targets for understanding the processes of stellar and planetary formation and evolution.

However, because M dwarfs are intrinsically faint, detailed observations have historically been limited, and early surveys suggested that more than 70% of them were single stars. Recent advances in observational techniques have revealed this observation to be incomplete: the frequency of low-mass stellar and substellar companions, such as brown dwarfs, may have been significantly underestimated.

Understanding how often such companions occur—and their mass distribution—is essential for distinguishing the similarities and differences between planet formation and star formation.

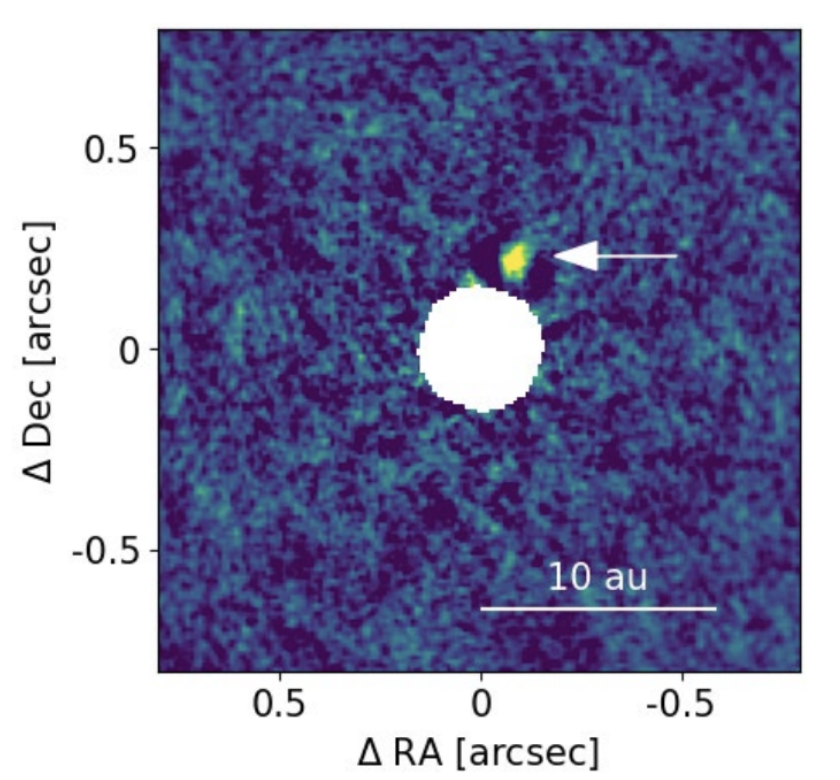

point-like source is detected close to the central star. The white arrow indicates the location of the new companion, brown dwarf J1446B. Credit: Taichi Uyama (Astrobiology Center/CSUN) / W. M. Keck Observatory)

Three-Pronged Approach

The key to this discovery was a three-pronged observational approach including Keck Observatory, Subaru Telescope and the Gaia Mission:

- Radial velocity measurements from long-term infrared spectroscopic monitoring with Subaru’s InfraRed Doppler (IRD) tracked the subtle wobble of the host star, caused by their mutual gravitational pull.

- High-resolution near-infrared imaging from Keck Observatory’s state-of-the-art adaptive optics on its Near Infrared camera (NIRC2) enabled the direct detection of the companion at a very small separation from its host star.

- The Gaia mission tracked tiny changes in the star’s position in the sky to further reveal the gravitational pull from the companion star. By integrating these datasets and applying Kepler’s laws, the team was able to determine the dynamical mass and orbital parameters of J1446B with unprecedented accuracy.

“Keck’s critical contribution was to make direct images of this Brown Dwarf companion which led to characterizing the object’s orbit and physical properties such as mass and temperature,” said Charles Beichman, Executive Director of the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute (NExScI) at Caltech and co-author of the study.

A Benchmark for Future Studies

The discovery of J1446B provides a critical benchmark for testing brown dwarf formation scenarios and atmospheric models. Combining future Gaia Data Releases and advanced spectroscopic data obtained from follow-up observations with new instrumentation – such as Keck Observatory’s HISPEC (High-resolution Infrared Spectrograph for Exoplanet Characterization) may enable researchers to map weather patterns, providing a step toward understanding planet formation and evolution. Perhaps, even, guiding us to a planet like our own.

Beichman concluded, “Remarkably, two Keck images showed variability in the Brown Dwarf’s brightness suggesting the existence of clouds and weather patterns. This combined approach will become more and more powerful, reaching down to the realm of gas giant planets like our own Jupiter, as new Keck instrumentation comes into operation.”

_1768613517521.webp)