Keck Observatory: Astronomers reveal tasty insights into exoplanet formation using ‘SPAM’

SPAM isn’t just for musubi.

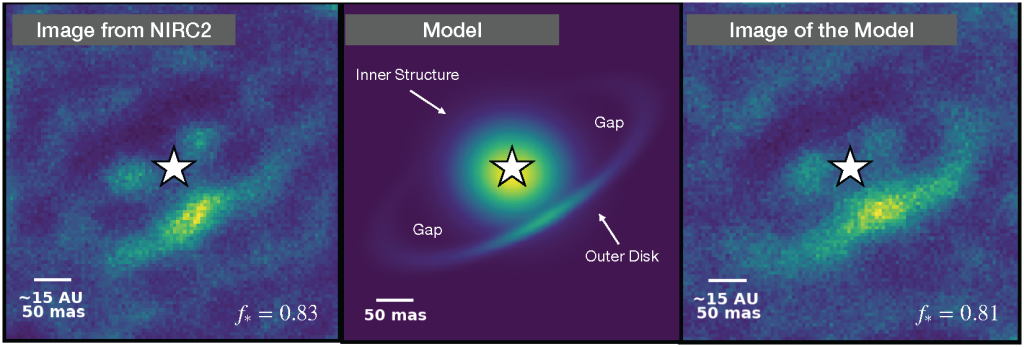

A new study using data from the W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea serves up the closest-ever view of a planet-forming disk around young star HD 34282 using the SPAM survey — The Search for Protoplanets with Aperture Masking, affectionately referred to as SPAM.

“We all want to know where we came from and how our solar system formed,” said Christina Vides, a graduate student at the University of California Irvine and lead author of the study published in The Astrophysical Journal. “By studying systems like this, we can watch planet formation in action and learn what conditions give rise to worlds like our own.”

Peering Into Planet Nurseries

The team used Keck Observatory’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRC2) which enables astronomers to see closer to a star than traditional imaging methods permit.

Their target, HD 34282, is a young star about 400 light-years away, surrounded by a thick ring of dust and gas—a “transition disk” thought to be sculpted by growing planets.

With Keck Observatory’s advanced instrumentation and adaptive optics, Vides and the team captured the most detailed view yet of the inner regions of HD 34282’s disk, revealing clumpy structures and brightness patterns that hint at possible planet-forming activity.

Although no confirmed protoplanet was detected, the observations provided the closest constraints yet on where a young planet could be hiding, as well as estimates of the star’s mass and accretion rate—key clues for modeling how its surrounding material might evolve into planets.

The Rarest of Discoveries

Early detection of protoplanets is exceptionally rare and technically challenging.

PDS 70 b and PDS 70 c are the only two confirmed protoplanets that have ever been imaged directly. Both were discovered in 2020 by Caltech observers also using Keck Observatory’s NIRC2 instrument.

Each new observation builds on that legacy, bringing astronomers closer to understanding how planetary systems emerge from swirling disks of gas and dust.

“This work is pushing the boundaries of what we can see,” Vides said. “Keck’s adaptive optics and masking capabilities make it possible to resolve features just a few astronomical units from the star—regions that are otherwise completely invisible.”

What’s Next

The team will continue using Keck’s advanced instruments to study other young stars with promising disks and compile more data for SPAM. The team is also preparing for observations using future instrumentation like SCALES, a next-generation high-contrast imager now being developed for Keck Observatory, which will expand the search for protoplanets in unprecedented detail.

“Every new system we study helps us understand a little more about how planets form and evolve,” Vides said. “It’s incredible that we can point a telescope at a young star hundreds of light-years away and actually see the conditions that could give rise to new worlds.”

_1768613517521.webp)