Summer ocean blooms studied with satellite imagery

A team of oceanographers led by the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa has published a study providing the first comprehensive look at the anatomy of massive microbial blooms that appear nearly every summer in the Pacific Ocean north of Hawai‘i.

For years, the origins of these vast swirls of color, as visible from space, remained a mystery. The findings, recently published by researchers from the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, synthesized multiple observational perspectives to explain the ecological processes driving these events.

“This paper represents a synthesis of many different observational perspectives which, only when evaluated together, allowed us to paint the whole picture,” said Rhea Foreman, lead author of the study and researcher in the Center for Microbial Oceanography: Research and Education in the UH Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. “It required multiple people with a range of expertises to work together in order to see the overarching ecological processes.”

Race to sample the bloom

The North Pacific Subtropical Gyre is often described as an ocean desert because of its low nutrient levels. However, in late summer, a partnership forms between diatoms, which are marine microbes living inside glass shells, and diazotrophs, bacteria that convert nitrogen gas into a usable fertilizer for the system.

While previous research established that this pairing drives summer blooms, the specific causes of how they start, stay alive and eventually collapse were unknown.

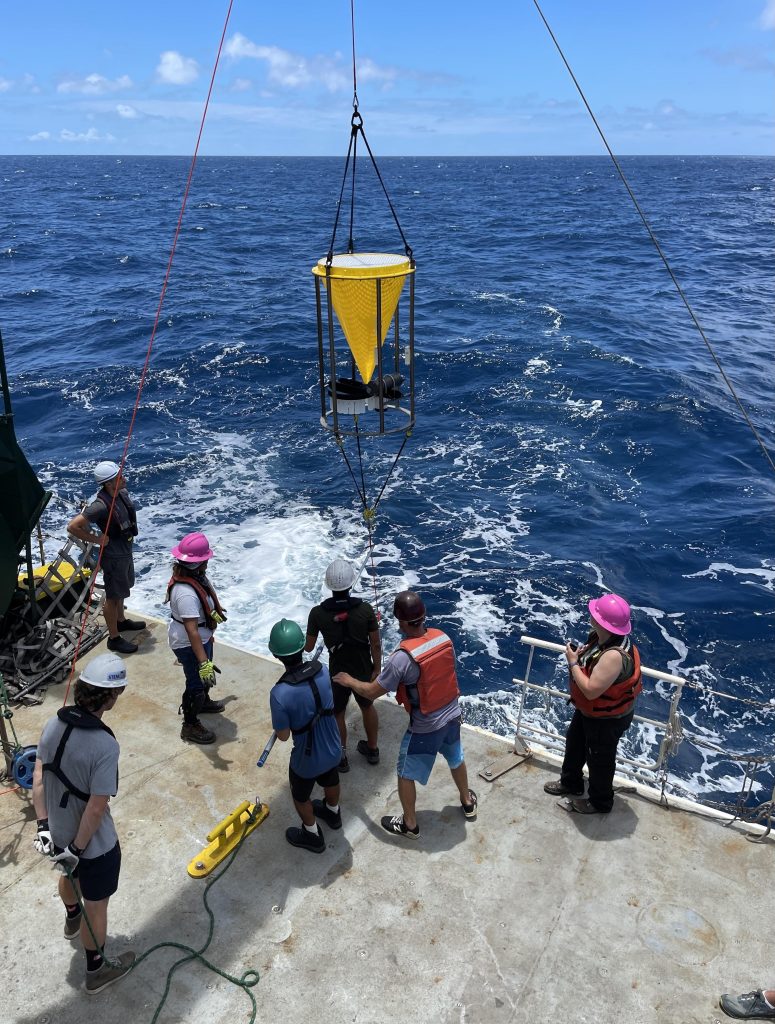

In the summer of 2022, oceanographers used the R/V Kilo Moana to try and catch a bloom event. When they noticed on satellite imagery that a bloom the size of Minnesota was within range of the expedition, a race was on to investigate.

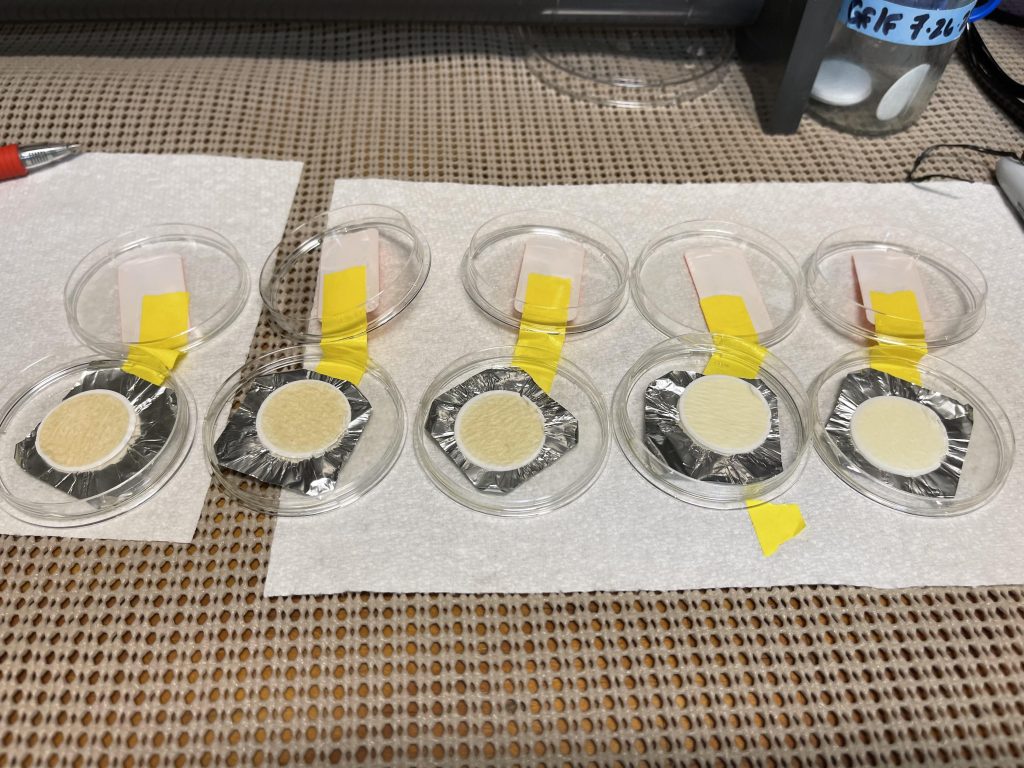

The team investigated the bloom’s microbial community, nutrient dynamics, composition of particulate matter, rates of photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation, and abundances of specific functional genes. Their study revealed that the blooms are likely triggered when the seed population of diatom-diazotroph associations experience favorable conditions such as: above-average concentrations of phosphate and silicate, and a shallower mixed layer at the surface ocean. This shallow mixed layer acts to corral the photosynthetic microbes, keeping them near the surface where sunlight is abundant—something they require for efficient nitrogen fixation.

“This comprehensive expedition required careful planning, skillful execution, effective teamwork and a bit of luck—we went four-for-four,” said David Karl, senior author on the study, Victor and Peggy Brandstrom Pavel, professor of Oceanography, and director of C-MORE.

Understanding lifecycles

The study also relied on the historical context provided by the UH Mānoa Hawai‘i Ocean Time-series (HOT) program that has conducted monthly monitoring of the physical, biological and chemical characteristics at a nearby open ocean field station north of the Hawaiian Islands since 1988.

“By comparing the 2022 expedition data to the HOT data, which shows baseline conditions at Station ALOHA, we were able to distinguish unique bloom characteristics from normal background conditions and that helped us understand the lifecycle of the bloom,” Foreman said.

The researchers’ proposed lifecycle for the blooms included some predictions about ways in which they collapse. They suggest that the phytoplankton may either run out of some nutrient (phosphate, for example), the mixed layer may deepen and inhibit growth, or mortality may increase though parasites, viruses or grazers that were originally in much lower abundances.

Because the diatom-diazotroph associations are heavy, they sink rapidly when they die and efficiently export carbon from the atmosphere to the deep ocean. Understanding the bloom’s lifecycle is key for modeling climate processes and predictions.