Volcano Watch — Handling the pressure: what gases trapped inside crystals tell us

Volcano Watch is a weekly article and activity update written by US Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists and affiliates. This week’s article was written by HVO post-doc researcher Heather Winslow.

Volcanic gases can give us critical information in the lead up to a hazardous eruption. USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists use permanent and portable gas monitoring stations to measure gas concentrations and emission rates above the surface of our volcanoes. But, to look at gases below the surface we turn to petrologists (a scientist who studies the origins of rocks and minerals), who can find gases trapped within volcanic rocks.

Gases within volcanic rocks can be measured to estimate gas compositions and magma storage depths before the lava erupted on the surface. In geology, we refer to gases below the surface as volatiles, referring to the elemental composition of the gas, which can be a solid, liquid, or vapor phase. When referred to as a gas, it means a volatile has transitioned into the vapor phase. The most common gases (or vapor phase volatiles) emitted at the surface are water (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), and sulfur dioxide (SO2).

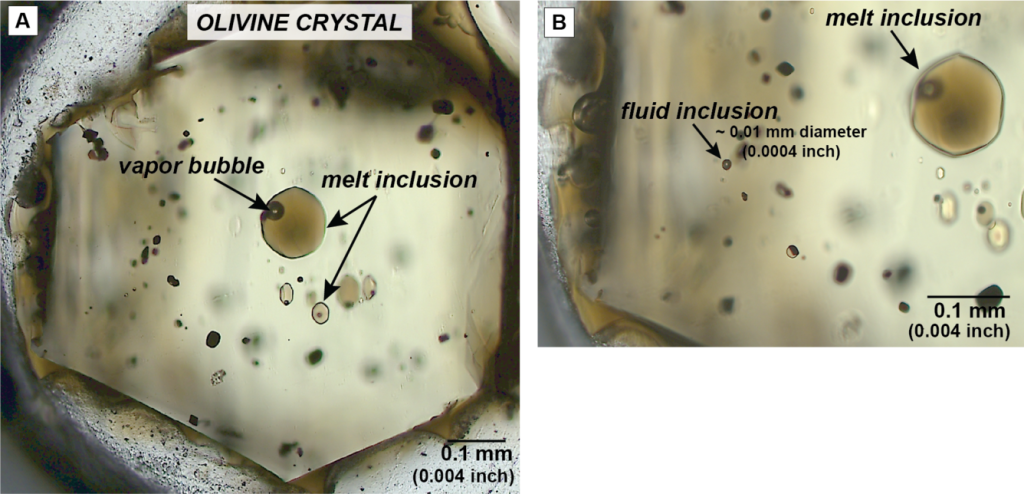

But how can we measure volatiles that are trapped within the magma before it erupts? By analyzing tiny droplets that become trapped within crystals such as olivine. These tiny droplets, called inclusions, can contain different materials. Melt inclusions contain the magma (in solid form), while fluid inclusions can contain drops of water (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), and sulfur dioxide (SO2) in the liquid or gas phase.

Once an inclusion has been trapped, the surrounding crystal acts as a pressure-capsule and retains information about the magma at the time the inclusion was formed.

In volcanoes, fluid inclusions are dominantly composed of CO2. At magmatic temperatures (1200˚ C or 2192˚ F), the density of the CO2 strongly depends on pressure, which is influenced by the depth of the magma at that point in time.

Thus, if we can measure the density of the CO2 within a fluid inclusion, we can estimate the pressure at which that fluid inclusion was trapped in the growing crystal and infer the depth under the volcano where the magma was when that crystal grew. Determining storage depths of crystals has large implications for how we understand volcanoes and how shallow or deep magmas reside below the surface before they rise to erupt.

Fluid inclusion density is measured by creating thin slices of the crystals that are analyzed using Raman Spectroscopy. One challenge in this process, however, is that fluid inclusions are so very tiny they can be hard to identify! They can range in size from approximately 0.01–0.1 mm (0.0004–0.004 inches) in diameter.

In 2025, HVO scientists conducted and participated in a short workshop on fluid inclusion sample preparation and identification at the University of Hawaiʻi, Hilo for undergraduate students and professors.

During the workshop, UHH students and staff learned laboratory techniques for identifying fluid inclusions and how to properly prepare the crystals for Raman Spectroscopy. This process is a recently developed method and results for magma storage depths can be attained very quickly after sample collection.

An undergraduate student in the UHH Geology Department helped initiate the fluid inclusion workshop because of their research interests in using this technique to estimate the depth magma was stored before recent Kīlauea eruptions.

The collaborative relationship between HVO and the UHH Geology Department has been strengthened over the years thanks to the cooperative agreement established in 1998. Through the agreement, UHH undergraduate students participate in eruption response and apply what they learn in the classroom directly to impactful work with HVO.

During each new eruption at Kīlauea, this technique provides another important tool for HVO scientists to understand hazards in Hawaii’s frequent eruptions. Preliminary results from episodes that span from mid-January 2025 to early July 2025 show that the magmas came from about 1 mile (1.5 km) deep beneath the surface, which is the location of the shallow Halema’uma’u magma chamber.

Volcano Activity Updates

Kīlauea has been erupting episodically within the summit caldera since Dec. 23, 2024. Its USGS Volcano Alert level is WATCH.

Episode 41 lava fountaining happened for just over 8 hours on Jan. 24. Summit region inflation since the end of episode 41 indicates that another fountaining episode is possible and could occur between Feb. 13 and 17 and is mostly likely between Feb. 14 and 16. No unusual activity has been noted along Kīlauea’s East Rift Zone or Southwest Rift Zone.

Maunaloa is not erupting. Its USGS Volcano Alert Level is at NORMAL.

Two earthquakes were reported felt in the Hawaiian Islands during the past week: a M3.1 earthquake 10 km (6 mi) E of Pāhala at 30 km (18 mi) depth on Feb. 7 at 5:59 p.m. HST and a M3.1 earthquake 8 km (4 mi) N of Hala‘ula at 39 km (24 mi) depth on Feb. 7 at 3:36 a.m. HST.

HVO continues to closely monitor Kīlauea and Maunaloa.

Visit HVO’s website for past Volcano Watch articles, Kīlauea and Maunaloa updates, volcano photos, maps, recent earthquake information, and more. Email questions to askHVO@usgs.gov.

_1768613517521.webp)