Sophisticated instruments gathering long term ocean water data near Lahaina fire

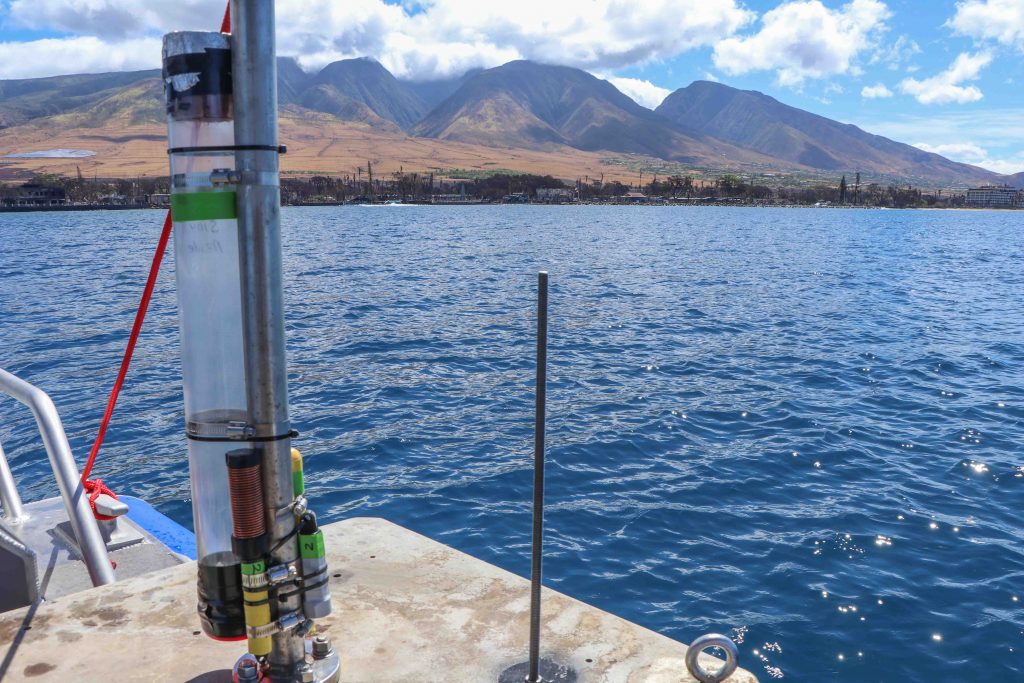

To measure the longterm affects of the Lahaina fire on nearby ocean waters, scientists are using three sophisticated sampling instruments that are on loan from the US Geological Survey.

The devices allow pollutants and toxins like heavy metals and pharmaceuticals to slowly slip inside a membrane and accumulate over time.

“This mimics what a living creature like coral or fish would absorb,” said Russell Sparks, an aquatic biologist with the state Division of Aquatic Resources. “When the samples are analyzed, we’ll have a much better idea of what the reefs are being exposed to as a result of this fire.”

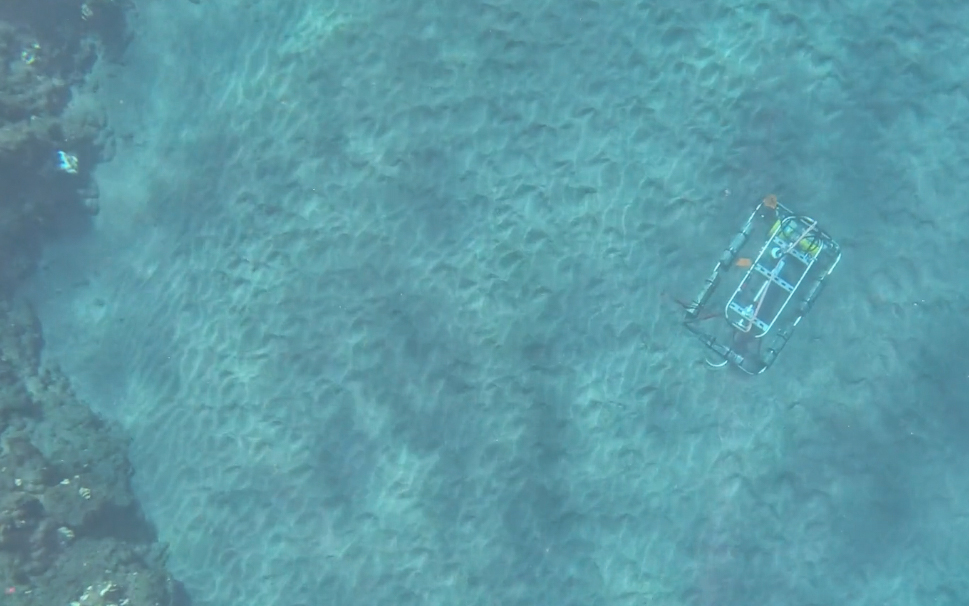

In partnership with the West Maui Ridge-to-Reef Watershed Initiative, the devices were placed in 15 to 20 feet of water last week. The initial samples will create a baseline and then the Division of Aquatic Services and the watershed initiative will work with the USGS over the next year or two to continue the process.

The trio of sampling devices, including passive chemical samplers and oceanographic sensors, were dropped offshore at Puamana in south Lahaina, just outside the Lahaina Small Boat Harbor, and near Mala Wharf.

“During clearing and debris removal from Lahaina and after any heavy rainfall events, we’ll get a better sense of what’s entering the system and where it’s going,” Sparks said.

Urban wildfires create, transform and release toxic chemicals into the environment where they enter water supplies and biota and are transported through the atmosphere and by way of runoff to the ocean.

The USGS will quantify initial post-fire types and concentrations of metals and toxic organic contaminants (volatile and persistent) in Maui in terrestrial ash/soil (at 28 sites) and marine reef sediment (at 10 sites).

Target contaminants include metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (persistent carcinogens created by biomass and fossil fuel burning), dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), PBDEs (flame retardants), PFAS (forever chemicals in fire-fighting foams and household products) and emerging contaminants from tire wear particles.

The initial post-fire assessment will inform longer-term environmental and runoff monitoring related to human and ecosystem health risks from the Maui wildfires, according to the USGS.

At the Lahaina Small Boat Harbor, teams also used a spring-activated sampler to collect sludge from the water just off a pier. Sludge will also be analyzed by the USGS lab in Santa Cruz, CA.

Based on visual observation, Sparks said the water quality inside the harbor is “horrible.”

“You can see it from the surface,” he said. “There’s a constant sheen of diesel and other pollutants.”

The accumulation of micro-debris, including pieces of fiberglass and degrading marine resources, is concerning if not removed.

“After all the vessels and debris are removed, the harbor is probably going to need some careful dredging just to prevent these contaminants from slowly and continuously releasing out onto the reef,” Sparks said.

The data will be shared with the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Health, the Environmental Protection Agency and others that can use the data to see how it may impact people.