Testimony at CWRM meeting centers on West Maui stream restoration, return of Mokuʻula

The state Commission on Water Resource Management held a marathon meeting on Maui Tuesday, lasting nearly nine hours. Members received testimony and updated the public on the Lahaina Aquifer Sector Area including wells in the fire-impacted area, water resources at Kauaʻula and Interim Instream Flow Standards (IIFS) for area waterways.

In reviewing the minutes from the last meeting, members described the 75 page document which included discussion on water management designations in West Maui, and the redeployment of CWRM Deputy Kaleo Manuel.

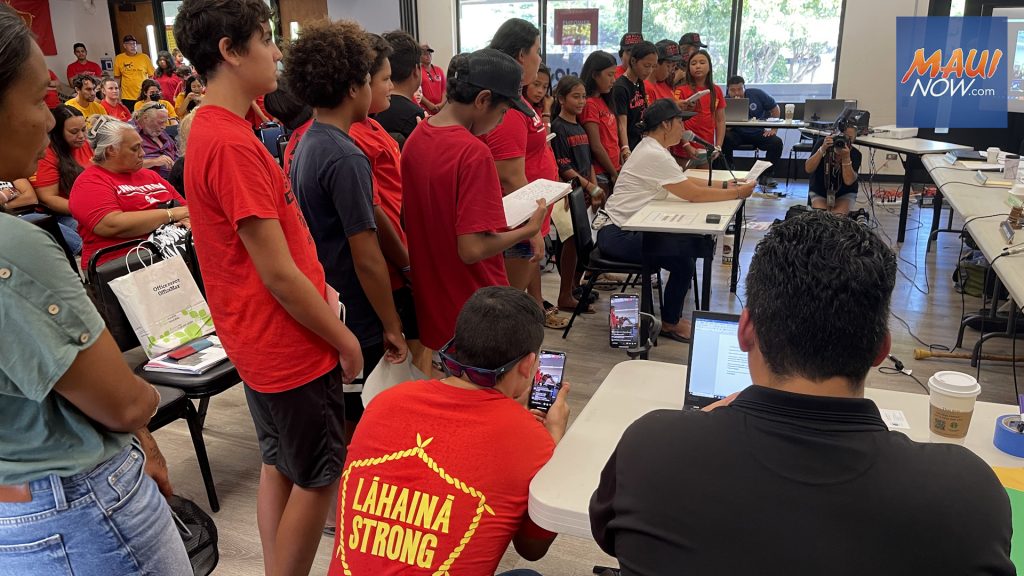

“I must say that in the history that I’ve been on this Board and Commission, I’ve never seen such a universal outpouring of support for a public official as well as an affirmation of the public trust principles that underlie the water code that this team—led by Kaleo [Manuel] and you chair [Dawn Chang]—are trying to rigorously and consistently apply,” said member Neil Hannahs.

Resident Palele Kiakona was among those who testified in support of Manuel’s return. “Today with the recent efforts like reinstating Kaleo [Manuel], reimplementing the water code and the IIFS, we are on a path to redemption, even though we are only back to square one.”

Kiakona said that central to the evolution of the area is its water. “These rivers are the ties bounding mauka to makai. The very allure that draws our visitors in to our shores, which ensures Hawaiʻi’s prosperity is the natural beauty that these waters sustain… Let’s not forget what happened to Lahaina. Now is a chance to right the wrongs,” he said.

Kauaʻula resident and kalo farmer, Keʻeaumoku Kapu explained the challenges he faced in the months leading up to the Lahaina fire. “We had water in our ditch, then our water dried up in April all the way to July when the state came in to put a monitoring system in while our water was being diminished. Then in August, as you can see because of the fire, the water returns back to our canal.”

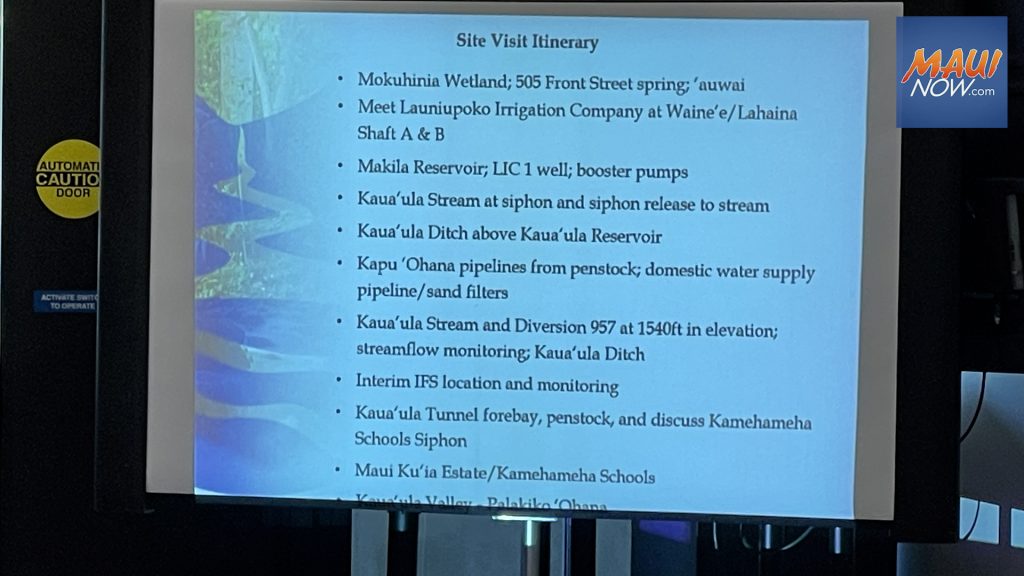

A site visit to the Lahaina Aquifer Sector and Kauaʻula was held last week on Oct. 18, 2023 at the request of Chairperson Dawn Chang, with commission staff and community stakeholders.

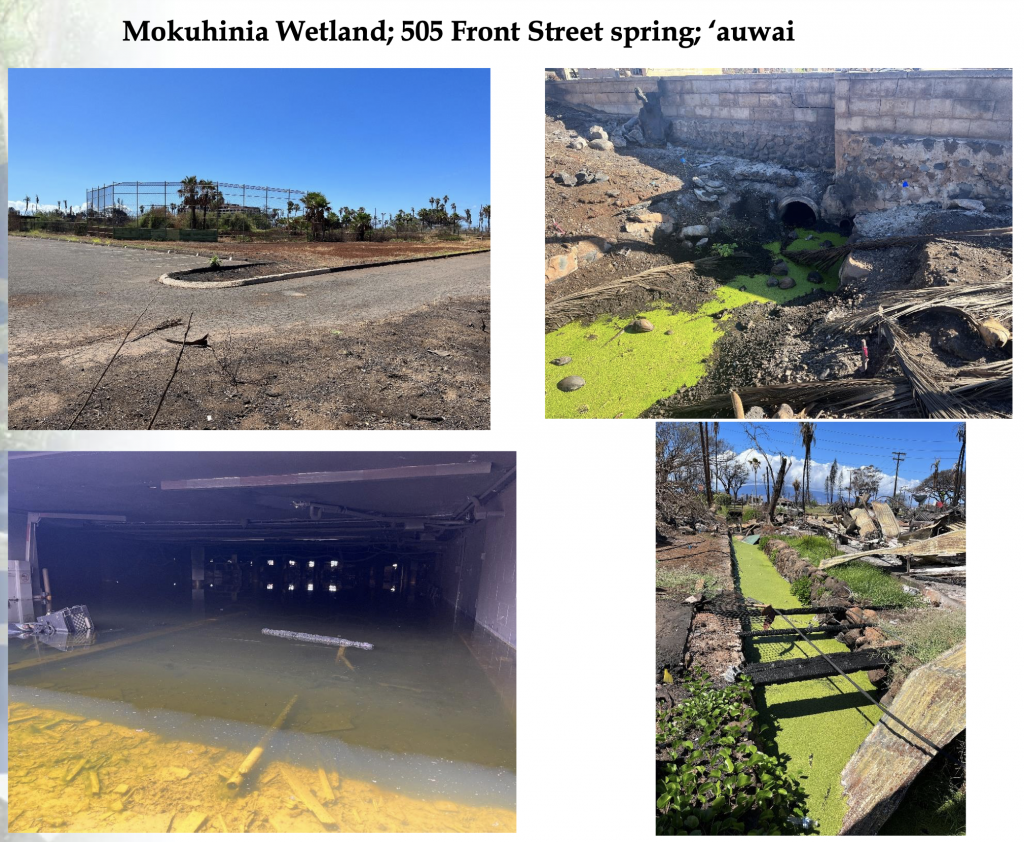

Makai of Kapu’s home, near Front Street is an area known presently as Malu Ulu O Lele Park. Beneath it is the remnants of Muku’ula, a small island and its surrounding waters of Mokuhinia. The once lush wetland area once served as the residence of royalty in centuries past and as a piko or center of traditional spiritual and government activity.

“Now we’re starting to see a return of the wai (water) into our wahi pana (legendary/sacred place). It’s only evident that I come here before the commission to ask you guys to cease all operations of these counterflow wells. They don’t belong there. They’ve dried up enough of our town,” said Kapu. “Your responsibility is to uphold the public trust to make sure that the residents of the town are not left behind.”

Kapu explained that above his property are others who are practicing customary and traditional rights. “They have lo’i kalo by the thousands in that valley. And if the state were to make a determination that only half of that valley shall flourish, then half of my family will suffer,” he said.

Staff with the Stream Protection and Management Branch described the site visit, in which members met at the Mokuhinia Wetland near 505 Front Street and proceeded mauka to the Kauaʻula reservoir, ditch and stream, and residential properties of the ʻohana Kapu and Palakiko.

“My suggestion for future action item would be: in order to meet the traditional and customary practice needs… to help restore the land at Ku’ia and provide domestic water needs, and to protect traditional and customary practices, in the stream, we need to release more water on the siphon,” state staff said during a presentation assessing Kauaʻula stream at Tuesday’s meeting.

Kauaʻula resident Uʻilani Kapu is advocating for a return of Mokuʻula and the wetlands of Mokuhinia near 505 Front Street. “You’ve seen our town destroyed… but you see the springs of water coming back. That’s what we need.

“We need that wai (water) traveling from top to bottom. That’s our ahupua’a system. That’s what brings life back to the ʻāina. It is our pivotal point. It is our sacred spot that needs to be recognized… We understand that restoring the natural paths of our wai in Maui komohana (west) is important not only to our environment, cultural practice… but are also necessary to mahi ʻai (farmers) and generations of water theft from our sacred wahi pana. Beginning the long process of environmental and spiritual healing, Maui komohana, and Moku’ula and Mokuhinia in particular, we must return what has been taken, including our wai,” said U’ilani Kapu.

Kala Tanaka, a kumu at Kula Kaiapuni o Lahaina spoke of her ancestors who farmed kalo and fished in Lahaina and Kahoma.

“The whole reason why they were able to do what it is they were able to do was because of the wai (water). And so we need it restored. The public trust needs to be restored… There’s so much more that needs to be done. There’s not enough wai (water) in Kahoma,” said Tanaka who urged members to put energy into restoring water to West Maui streams.

“We already know that those are the processes that will deter the fires that are happening. Everybody knows we’re in climate change. And looking at disaster resilience, these are the types of plans that we need to have happen… We put the water in our streams, our kalo farmers at the top, and purveyors at the bottom. That’s how it’s supposed to be,” she said.

Fellow Kula Kaiapuna teacher, Kanoelani Steward of Lahaina issued a plea, “Put our ʻāina first. Put us first—the kupa (citizens) and keiki (children) of Lahiana—and cultural practices that breathe ea (life/air) into our ʻāina (land).”

West Maui resident Kapali Keahi feared that history could repeat itself if action is not taken to protect water for traditional uses. “We knew before Launiupoko was built up that it was going to be an added stress on Kauaʻula, because that’s the only way they would be able to develop Launiupoko is to take water from Kauaʻula. And here we go again.”

“We need to reverse some things… because it is unreasonable for development to take place in that area if Kauaʻula is in this situation,” said Keahi. “If we are to see that Mokuʻula is to be restored… if the developers actually think they have a seat at the table, then we’re going to have problems because already as is, we can tell that because the water is not being used, because the wells are in disrepair… the water is returning back to Mokuʻula. We can see that the use of those wells is an adverse effect on Mokuʻula. So we have to entertain the idea of course that those wells are not to be used again so that Mokuʻula can come back, so that Mokuʻula can be restored… It is well within our rights… within our customary and traditional rights to worship that area, to worship the moʻo [Kihawahine].”

Testifier Palele Kiakona said, “Historically we’ve diverted our precious water for various industries. While these actions sustained our people during the plantation era, where there was at least some resemblance of respect for our ʻāina, today’s exploitation by the hotel industry and development seems unabated and disregards our natural treasures.”

“The ongoing struggle over water management in West Maui is very well documented,” said Maui resident Tiare Lawrence testified as a representative of the nonprofit Kamalu o Kahalawai. “In light of the devastation we are currently healing from, we are now presented a once in a lifetime opportunity to make right the historical wrongdoing on our people by Pioneer Mill, the tourism industry, and governing entities,” she said.

“There is hope among many people in this room that the ecosystem and kanaka can flourish together once more… There’s a lot of talk about resilience and the rebuild of Lahaina, and I can’t imagine a resilient Lahaina if we continue the mismanagement of land and water moving forward. When we talk about water resource management, we also need to talk about tourism management,” said Lawrence.

On the topic of Mokuʻula and Mokuhinia she wondered how springs can come back at Mokuʻula if ground water is being pumped from the area.

“I’m not a geologist, but when you’re pumping ground water from an area where you need spring water, I just think it’s irresponsible for the commission to allow that Pioneer Mill well to continue to be used… they are currently taking water from that area to go and support luxury estate developments in Launiupoko and Makila. I would implore you guys to look into that,” said Lawrence.

“For me, when the fire happened, as tragic as it was, I can tell you this: that our 81-year-old tūtū from our ʻohana escaped the fire, and the day after the fire we sat at the dinner table, and you know what he said? He said Lahaina needed to be cleansed. So with that being said, now more than ever, discussion of the restoration of Mokuʻula and Mokuhinia should be taken seriously,” said Lawrence.

At the conclusion of the meeting Chair Dawn Chang said, “I don’t make any guarantees to any of you. We are going to do our best. I think we’ve heard a lot of what the people who show up—we’ve heard what you have to say.”

CWRM will meet again on Nov. 21 in Honolulu, and once again before the end of the year on Dec. 19, 2023.