Maui Council explores ways to reduce alarming rate of ocean drownings

Maui County faces a disproportionately high rate of ocean drowning fatalities, driven largely by the high number of visitors lured by the ocean’s beauty but unprepared for its hidden dangers.

This alarming rate was the focus Monday for members of the Maui County Council Water Authority, Social Services and Parks Committee. The panel heard presentations on drownings in the county and discussed ways to improve safety for people venturing into the ocean and pools.

Data presented by Garrett Hall, acting state Emergency Medical Services chief and State Trauma Program manager for the Department of Health, highlighted that the state ranks second only to Alaska for drowning fatalities nationwide.

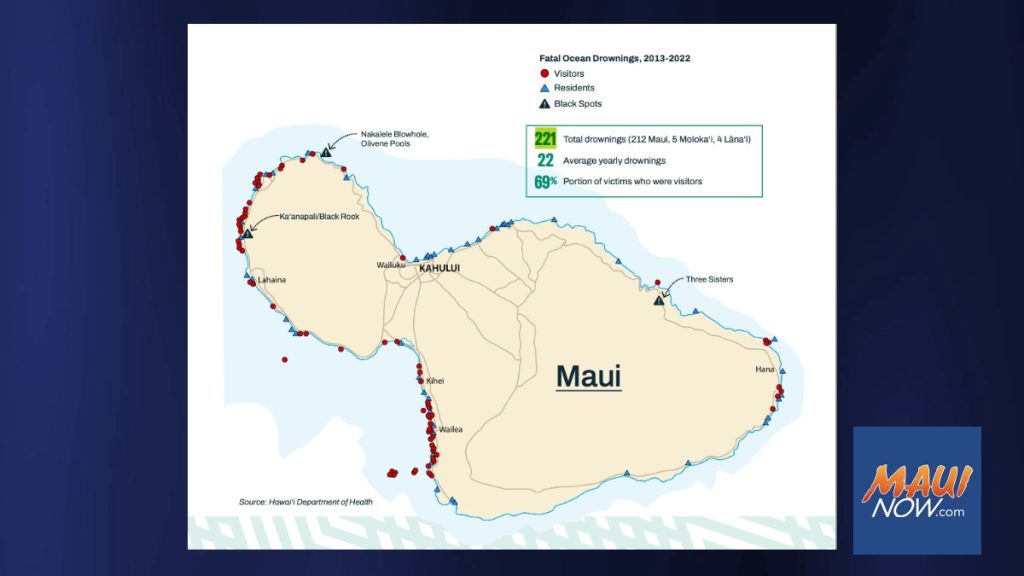

More specifically, data for ocean drownings from 2013 to 2022 showed 221 total fatalities in Maui County, with the vast majority on Maui island (212), five on Molokaʻi and four on Lānaʻi. Visitors made up 69% of these victims.

Maui County averaged 22 drownings annually during the 10-year period. The average per capita rate of drownings was twice as high on Neighbor Islands as on Oʻahu, according to the 2025 Hawaiʻi Water Safety Plan.

Staffing challenges and unguarded beaches

Much of the committee discussion was on extending ocean safety services to unguarded, high-traffic visitor areas such as Wailea Beach and Kāʻanapali. Ocean Safety Bureau Chief Zach Edlao emphasized that drowning incidents are a tragedy that typically occur outside of guarded beaches, necessitating a multi-pronged safety approach, and highlighting the challenge of “guarding the unguarded,” not to mention the unaware.

“They see the beauty. They don’t see the beast,” he told council members of people attracted to the ocean but seemingly blind to its inherent dangers.

“It’s our job to educate them and to minimize these injuries,” Edlao said. “And we cannot do that if we’re not there at the beaches.”

Public education efforts include modern media and public outreach such as community events or visiting schools to teach students about ocean safety and awareness of “hazards in and around the ocean.” Getting students into the water to practice water safety and stay afloat is “a huge difference in Hawaiʻi,” he said.

The Junior Lifeguard Program is a “big one” for providing ocean safety education especially to children 8 to 11 years old in Maui County, he said. “There’s so many keiki that we have to turn away because we don’t have enough people to help, supervise the program, especially for the sake of control,” Edlao said. “But the amount of young keiki we have is tremendous.”

Edlao identified Puʻu Kekaʻa (Black Rock) as a target area for expanded services in Maui County. However, the immediate barrier to deploying lifeguards is the bureaucratic process, specifically permits.

“The struggle with the permits we have is beyond me,” he told council members. Lifeguard towers are not permanent structures and should be granted exemptions to expedite their placement, he pointed out.

The second major challenge is recruiting and retaining qualified staff. Edlao said that hiring is a struggle due to the cost of living and insufficient pay. He explained that many qualified individuals choose to work in the private sector for immediate financial benefit rather than waiting years to reach a livable wage with the county. This results in the loss of “good people” who need to earn money to manage the cost of living.

Edlao also stressed that the department maintains a rigorous physical agility test to ensure they hire “quality lifeguards,” not just anyone. The starting salary for an ocean safety officer, after probation, is around $56,000, which many speakers said is not a livable wage given the cost of living, contributing to recruitment difficulties.

Edlao said a December ocean safety recruit class had spots for eight new officers but received only four candidates. “There’s a lot of our guards that are considering going elsewhere because of the pay,” he said. “It’s tough living here in Hawaiʻi and what can you do? They gotta support their families.”

Edlao introduced the long-term vision of creating an Ocean Safety Prevention Bureau dedicated year-round to education, outreach, and working with hotels and schools. The chief indicated that this expansion would be reflected in budget requests over the next five years.

Industry partnerships and prevention

Kīhei resident Mike Moran testified about the impracticality of expecting visitors staying at high-end resorts along Wailea Beach to drive several miles to guarded locations like the Kamaʻole beaches a bit further north. “We have to provide some kind of safety here,” Moran said, referring to the resort beaches.

John Pele, executive director for the Maui Hotel & Lodging Association, and Naomi Cooper, deputy director, expressed industry concerns and a willingness to explore public-private partnerships to ease the financial and workforce burden on the county. Pele cited an example in West Maui where the Kāʻanapali Operators Association is reportedly looking to fund and build lifeguard stands.

Department of Parks and Recreation Pools Manager Duke Sevilla emphasized a similar struggle to recruit pool lifeguards, a key factor limiting the availability of low-cost or free public swim lessons. Sevilla noted that they are operating some pools, like Kīhei, with as few as three staff members when they require six or seven.

Kirsten Hermstadt, executive director for the Hawaiian Lifeguard Association, detailed a Junior Lifeguard Internship Program piloted on Kauaʻi, which trains teens as if they were new recruits and employs them as pool lifeguards. This program addresses pool staffing shortages and creates a professional development pipeline. Hermstadt suggested that the Council could help by working to lower the federal hiring age for pool lifeguards from 18 to 16, a change already implemented on Oʻahu.

Council Member Nohelani Uʻu-Hodgins proposed partnering with the hotel industry for more “realistic” and graphic safety videos. Current presentations feature a “beautiful flight attendant talking about the risk assessment,” and “we’re not watching or paying attention,” she said.

Uʻu-Hodgins suggested the messaging about ocean safety be framed in a “more realistic” and “honest way.” It’s “kinda gotta be a little bit more gruesome about what it looks like,” she said, recalling grim messages about the dangers of drinking and driving in high school.

Legislative hurdles and next steps

Council Chair Alice Lee urged the Ocean Safety Division to present a comprehensive, prioritized plan with specific funding requests ahead of the upcoming budget session. “We are more than willing to provide the adequate funding that is required and seems to be lacking,” Lee said, “but we do need a plan.”

The Department of Health report identified several existing “Hot Spots” and “Black Spots” for drowning in Maui County, including Kāʻanapali/Puʻu Kekaʻa “Black Rock,” Lahaina, Nākālele Point, “Olivine Pools,” Kīhei, Wailea and Hāna.

The committee deferred action on the matter.