Keck Observatory: Astronomers sharpen the universe’s expansion rate, deepening a cosmic mystery

A team of astronomers using a variety of ground and space-based telescopes including the W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea, Hawaiʻi Island, have made one of the most precise independent measurements yet of how fast the universe is expanding, further deepening the divide on one of the biggest mysteries in modern cosmology.

Using data gathered from Keck Observatory’s Cosmic Web Imager (KCWI) as well as NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) the Very Large Telescope (VLT) and European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) researchers have independently confirmed that the universe’s current rate of expansion, known as the Hubble constant (H₀), does not match values predicted from measurements from the universe when it was much younger.

The finding strengthens what scientists call the “Hubble tension,” a cosmic disagreement that may point to new physics governing the universe.

“What many scientists are hoping is that this may be the beginning of a new cosmological model,” said Tommaso Treu, distinguished professor of physics and astronomy at the University of California Los Angeles and one of the authors of the study published in Astronomy and Astrophysics.

“This is the dream of every physicist. Find something wrong in our understanding so we can discover something new and profound,” added Simon Birrer, assistant professor of physics at the Stony Brook University and one of the corresponding authors of the study.

A constant in question, questioned constantly

Coined by astronomer Edwin Hubble, who first calculated it in 1929, the Hubble Constant is the rate at which the universe expands. This number reveals not only the universe’s current speed of growth, but also its age and history.

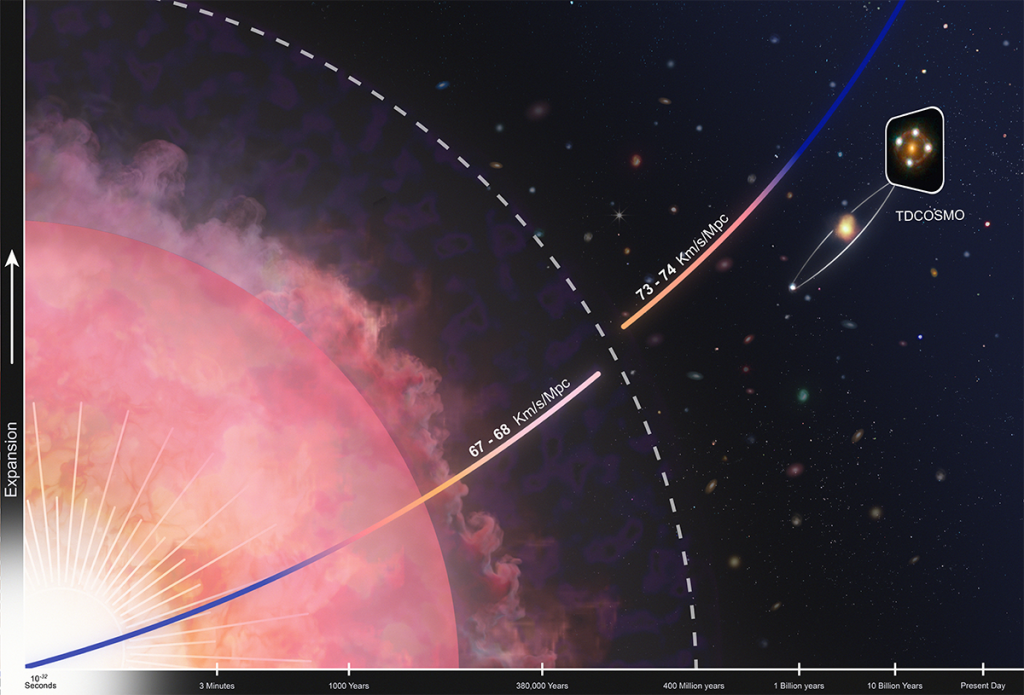

Yet nearly a century later, scientists still can’t agree on its exact value. The Hubble Constant can be measured in two ways, one probing the universe at early times and another probing the universe at times near today. The early universe probe, which uses cosmological models to indirectly provide the current expansion rate of the universe, favors an expansion rate of ~67 km/s/Mpc; and the late (nearby) universe probe, which measures the local universe as it exists today favors an expansion rate of 73 km/s/Mpc. Measurements based on the nearby universe differ from predictions drawn from the early universe, resulting in what is famously known as the Hubble tension.

Confirming this tension would force scientists to rethink the very makeup of the cosmos; perhaps revealing new particles, or evidence for an “early dark energy” phase that briefly accelerated expansion after the Big Bang. Because the implications are so profound, astronomers stress the importance of multiple independent methods to cross-check the result.

“This is significant in that cosmology as we know it may be broken,” said John O’Meara, chief scientist and deputy director of Keck Observatory. “If it is true that the Hubble tension isn’t a mistake in the measurements, we will have to come up with new physics.”

A new way to measure the universe

To make this precise measurement, the team used a method called time-delay cosmography. Much like a funhouse mirror bends and distorts reflections, massive galaxies bend the light of more distant galaxies and quasars, producing multiple images of the same object.

When the distant object’s brightness changes, astronomers can measure how long it takes those changes to appear in each image. Those “time delays” act like cosmic yardsticks — allowing scientists to calculate distances across the universe and, ultimately, determine how fast it’s expanding.

KCWI’s powerful spectroscopy was essential to the measurement. By observing the motion of stars within the lensing galaxies, the instrument revealed how massive those galaxies are and how strongly they bend light, critical information for pinning down the Hubble Constant.

“The key breakthrough relied on the motion of stars in the lens galaxies as measured via Keck/JWST/VLT spectroscopy to address the main source of uncertainty, known as the mass-sheet degeneracy,” said Anowar Shajib, postdoctoral fellow at the University of Chicago, and a corresponding author of the study. “The result also relies on long-term collaborative work between observatories including time delay measurements from 20 years of photometric data obtained at ESO in Chile.”

The quest continues

The team’s measurement currently achieves 4.5% precision — an extraordinary feat, but not yet enough to confirm the discrepancy beyond doubt. The next goal is to refine that precision to better than 1.5%, a level of certainty “probably more precise than most people know how tall they are,” said Martin Millon, postdoctoral fellow at ETH Zurich and the third corresponding author of the study.

_1768613517521.webp)