Kaniakapūpū is an off-limits cultural site, but virtual tour provides legal way to explore site

Kaniakapūpū, the summer palace of King Kamehameha III, lies within a restricted watershed in a densely forested part of Nuʻuanu on the island of Oʻahu. The site is closed to people, with the exception of Native Hawaiian cultural practitioners or permitted caretakers.

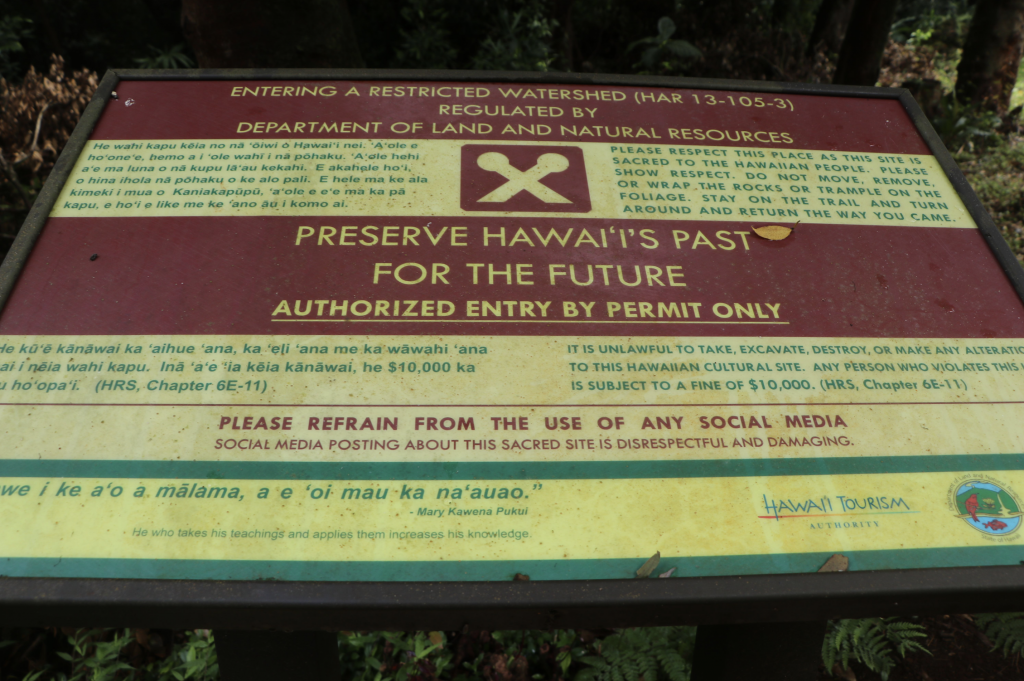

But officials with the state Department of Land and Natural Resources say, “It remains irresistible to visitors, who trespass onto the site. Signs at the ruins inform hikers of the closure but web searches counter the warnings. Numerous travel blogs promote the site as a fun day hike, and photographers document themselves standing on the ruins and breaking the law.”

A new virtual tour provided by the DLNR Division of Forestry and Wildlife aims to counter online misinformation while also giving interested users a chance to learn about the site in a manner that is safe, legal, and respectful.

Now available on the DLNR website, the tour utilizes a series of navigable 360˚ images combined with audio collected at the site. It also features historical photos and oral history provided by a local expert. Dr. Baron Ching, who runs the non-profit stewardship group ʻAhahui Mālama O Kaniakapūpū.

In the videos, Dr. Ching discusses the cultural and historical importance of Kaniakapūpū, including its distinction as the site where King Kamehameha III drafted the 1839 Declaration of Rights and the first constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi in 1840. Kaniakapūpū also hosted enormous celebrations of Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea, the day of restoration after the short-lived British occupation of Hawaiʻi in 1843.

“In the past, we’ve tried to protect Kaniakapūpū by not putting information about it online, thinking that anything we post will just make people more inclined to go there,” said Ryan Keala Ishima Peralta, a DOFAW forest protection supervisor in a department press release. “That hasn’t worked, as the misinformation is already online with directions and photos. We now want to protect Kaniakapūpū by having our information front and center. We’d like people to learn about this site and the first thing we want them to learn online is why it is closed, and why it deserves protection and respect.”

The virtual tour offers official information on the site’s closure and the legal opportunities for access. People who aren’t practitioners but want to help can contact ʻAhahui Mālama O Kaniakapūpū to sign up for volunteer days to remove weeds growing near the ruins. All other potential visitors looking for directions or online information are informed that access is prohibited and that they could be fined up to $10,000 for damage to the site.

Much of the information on the new DLNR webpage is aimed at photographers, who have posted photos of themselves standing on the nearly 200-year-old ruins or even inside the bedroom window of King Kamehameha III.

The website provides a shareable social media badge proclaiming “I helped protect Kaniakapūpu by going virtual” and giving directions to the new tour. The website even provides an option to create a “virtual selfie” where users can overlay a photo of themselves onto the social media badge, as an alternative to taking a selfie at the site in person.

By encouraging users to share their badges on social media with the hashtag “#kaniakapupu,” DLNR hopes that when potential visitors search for information online they will find the virtual tour rather than only finding inaccurate information.

_1768613517521.webp)