Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative

Hawai‘i Journalism InitiativeAir Force advances plans to build 7 more telescopes on Haleakalā as fuel spill cleanup continues

In the summer of 2015, Maui resident Tiare Lawrence stood with hundreds of protesters to block the delivery of telescope parts from reaching the summit of Haleakalā, a place Native Hawaiians call “wao akua,” the realm of the gods.

The $344 million project to build the world’s largest solar telescope went forward anyway, and became fully operational in 2020.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative's weekly newsletter:

Now Lawrence, a community organizer with the group Kāko‘o Haleakalā, is gearing up for another fight as the U.S. Air Force outlines plans to build up to seven more telescopes on the summit, even though it has not finished the cleanup of a 700-gallon fuel spill from 2023.

“Why should we allow them to continue to desecrate the most sacred space on this island?” Lawrence told the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative.

The Air Force says it needs the new telescopes to enhance its ability to track satellites and other objects in space at a time of growing threats. But community members like Lawrence question why the military is forging ahead in the face of widespread pushback, including from Maui County Mayor Richard Bissen, who sent a letter stating the county’s opposition in 2024 when the proposal first came out, and all nine members of the Maui County Council, who passed a resolution opposing it in 2024.

This week, the Air Force will hold two public hearings to get input about the project’s draft environmental impact statement, which was released in January. The meetings will run from 6 to 9 p.m. Tuesday at the Kīhei Community Center and Wednesday at the Mayor Hannibal Tavares Community Center in Pukalani.

Haleakalā has housed a growing number of defense and research facilities since the 1950s, when the exceptionally clear skies above the 10,000-foot summit caught the attention of astronomers. In 1956, the U.S. Army started a six-month star-tracking project at Haleakalā, one of the earliest programs there. The University of Hawai‘i followed with a satellite tracking facility in 1957.

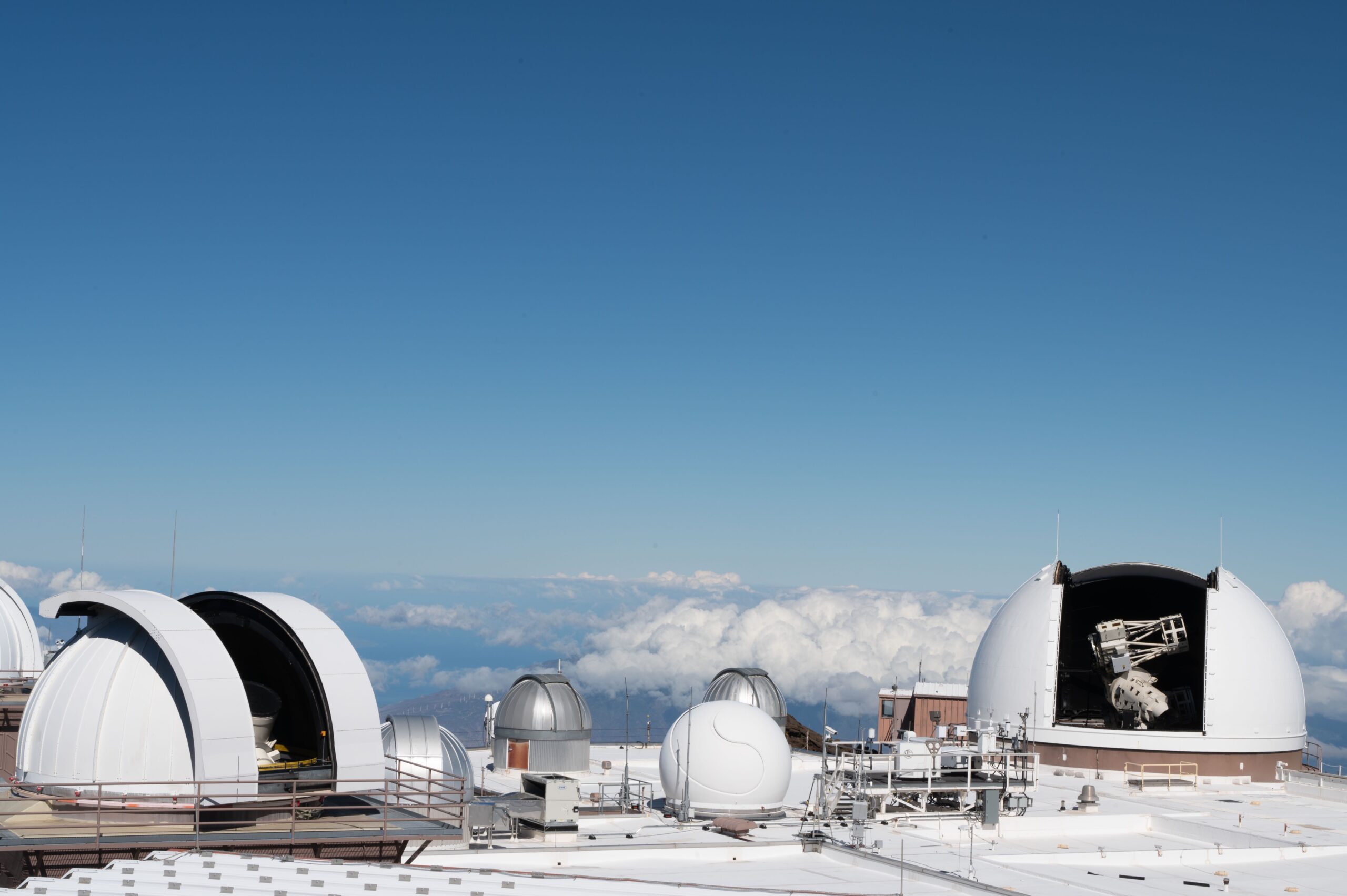

Today, six academic and four space surveillance telescopes sit on 18 acres at the summit.

Now the Air Force wants to build and operate up to seven more domed telescopes that would become known as AMOS STAR: the Air Force Maui Optical and Supercomputing Site Small Telescope Advanced Research facility. One would be built on the rooftop of a current building, while six additional ground-mounted telescopes would be installed on new concrete pads. The site is less than 1 acre.

According to the draft report, the telescopes would “provide enhanced dedicated satellite tracking and communication capability.” The Air Force says advancing technology is crucial in the face of “growing challenges and threats in space, including the increasing amount of space debris and the proliferation of objects in orbit, which pose appreciable risks to operational safety, national security and global space assets.”

The Air Force Research Laboratory, which would operate the telescopes, is responsible for tracking about 48,900 space objects, including active spacecraft and pieces of debris in Earth’s orbit over the Pacific region. AMOS is one of two major telescope sites that it uses for this purpose. The other is in New Mexico.

“To expand these capabilities, additional telescopes are required at a site with favorable viewing conditions in the Pacific region,” the draft report says. “This region provides the optimal geographical advantages needed to monitor critical areas of space not adequately covered from other locations.”

Construction is expected to start around 2026 to 2027 and last about two years. The project’s cost is estimated at about $5.9 million.

The Air Force did not make officials available for interviews by Friday but said in an email announcing the hearings that the department has “identified multiple mitigation strategies” to ensure the facility is in compliance and to “safeguard community well-being.”

About 500 people attended public scoping meetings in 2024 — with heavy opposition to the project — and their comments were incorporated into the draft report, said Capt. Kali Gradishar, who handles public affairs for the U.S. Space Force Combat Forces Command.

“The current AMOS team contributes to the local economy employing island residents, interacting with local businesses, and bringing an estimated $30 million in annual salaries to the state and employed residents,” Gradishar said. “While most of the proposed telescopes will be remotely operated to reduce personnel footprint at the summit, most of the operators and maintenance personnel for the systems will be local long-term residents, adding to the local economy.”

For Lawrence, the economic pros don’t outweigh the cons. If anything, Hawai‘i needs to diversify its economy to be less dependent on tourism and the military, she said. She worries that an expansion of defense telescopes will make Maui even more of a target in the middle of the Pacific between an unpredictable Trump administration and adversaries like Russia, China and North Korea.

“They are literally bringing space wars to our island,” Lawrence said.

It’s not just the threat of war that the military brings. Mikahala Helm, vice president of Kilakila ‘O Haleakalā and a University of Hawai‘i Maui College professor emeritus, said the community had long been wary about “the toxic material” stored at the summit, and those fears eventually came to fruition.

On Jan. 29, 2023, a malfunctioning generator during a lightning strike leaked about 700 gallons of an 80-20 mixture of diesel and jet fuel onto a concrete pad and the surrounding soil, contaminating about 750 square feet in the immediate vicinity and another 400 square feet downslope from storm runoff.

Then-Brig. Gen. Anthony Mastalir, who was commander of the U.S. Space Forces Indo-Pacific at the time, expressed “tremendous remorse.” Then-Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall flew in from the Pentagon to apologize. The military vowed to go “above and beyond” to clean it up.

The four-phase cleanup process started in March 2023 with the excavation of about 30 cubic yards of soil in March 2023. The second phase, an assessment of the site, started in July 2023.

Last year, the state Department of Health approved the Air Force’s final cleanup plans, which include “bioventing,” a process of pumping air into the soil to help break down the contaminants. Because of how long it’s been, the lighter jet fuel is “expected to have largely evaporated, with the heavier diesel fuel remaining in site soil,” the plan says.

Space Force officials told Military.com in March 2025 that the full cleanup could take as long as 2032.

Bioventing facilities have been operational at the summit since July, and active monitoring and testing will likely continue for the next three to seven years, the military said Wednesday.

“Restoring the land in a way that is culturally informed has been and continues to be our top priority to ensure we do this right,” U.S. Space Force Lt. Col. Douglas Thornton, 15th Space Surveillance Squadron commander, said in a news release.

Lawrence said she finds it “unbelievable” that the department wants to build more telescopes before the cleanup is finished.

“You’re the military,” Lawrence said. “You have access to all these resources to clean it up, and why is it taking you this long?”

When the spill happened in 2023, she wasn’t surprised. The incident came on the heels of decades of “environmental degradation” that included bombing exercises on Kaho‘olawe and Pōhakuloa that began in World War II and a 21,000-gallon jet fuel spill at U.S. Navy facilities that poisoned drinking water on O‘ahu in 2021.

“The military obviously doesn’t care,” Lawrence said. “They don’t respect our culture and our land the way that we do. And I think it’s time to have serious discussions of what the military presence will look like in Hawai‘i in the years to come.”

The Air Force’s future at the summit could be up for debate soon. Its leases with the Federal Aviation Administration and the state Department of Land and Natural Resources are up in 2027 and 2031, respectively.

Kī‘ope Raymond, a retired professor of Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawai‘i Maui College, said the military’s presence in the islands “didn’t happen yesterday.”

“This has been something that has been ongoing since the military came ashore on its way to fight in the Philippines in the Spanish-American War” of 1898, Raymond said.

That was the same year the U.S. annexed Hawai‘i and five years after it illegally overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom.

“We are illegally occupied territory,” Raymond said. “We are existing in a place that shouldn’t have the United States as the governing entity.”

Raymond is also the president of Kilakila ‘O Haleakalā, an organization created in 2005 under the late Ed Lindsey. With the help of the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, the organization filed four lawsuits from 2010 to 2012 related to the decision-making process of what would eventually become the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope.

They won two, including one that voided a permit because the state Board of Land and Natural Resources had not given the group a contested case before granting it, and another that allowed the group to access records withheld by UH related to political pressure on the approval of the telescope project.

But ultimately, the lawsuits and a series of protests in 2015 and 2017 weren’t able to stop approvals for the telescope, which has been in operation for about five years.

Raymond said the military has “already been clearly told from many different perspectives” that the public does not want more telescopes. Similarly, the military also justified the bombing of Kaho‘olawe as necessary for national security at the time.

But the movement to save the island holds a takeaway for Raymond: “The United States military has been stopped before.”

Raymond hopes for a moratorium on more telescopes on Haleakalā and thinks a long-term management plan that brings together all of the players at the summit is needed. On Hawai‘i island, massive protests against plans for the Thirty-Meter Telescope on 13,800-foot Maunakea led to the creation of a new advisory board made up primarily of Native Hawaiians to oversee future management of the area.

When asked about a moratorium or another possible solution, Kenneth Chambers, director of Pan-STARRS, two of the telescopes operated by UH’s Institute for Astronomy with NASA funding, said “those conversations have to happen” and that inclusion of the Hawaiian community is important when talking about the future of Haleakalā.

Chambers sees a public benefit in the academic work of researchers, which he said is different from the military’s mission. Every night, Pan-STARRS surveys the sky to collect data that help build “a very deep image of the sky over time” and track near-Earth objects. They find about 1,000 a year, about three a night on average, and also dozens of potentially hazardous objects. Ideally, the goal is to find those objects while they’re still a couple of years away, giving time to work out “deflection strategies.”

“Pan-STARRS is humanity’s insurance policy on this particular risk of asteroid impact,” Chambers said. “The risk is very, very small. But the potential damage is very, very large.”

Astronomers’ findings are publicly available, Chambers said. By contrast, the military does not share its data, so it’s hard to know whether they truly need more telescopes. Their operations “have nothing to do with astronomy, they have everything to do with politics” and tracking the activities of other countries, Chambers said.

“The fundamental problem with defense work is, outside of it, we don’t know what we don’t know, right?” Chambers said. “It may be necessary to do it, but we can’t know by the very nature of it.”

For Lawrence, who can see the summit every day from her Upcountry home, the ultimate solution is to decommission all of the telescopes on the mountain and “just let Haleakalā be Haleakalā.” Growing up, she was taught that “if I don’t have a reason to go up there, then I don’t belong up there,” and she only takes her children to visit during the summer or winter solstice to bring ho‘okupu, or offerings.

Helm goes up for cultural ceremonies “when it’s the time,” but she said measuring the importance of Haleakalā by how many times a person visits is a Western way of thinking.

The beauty and the meaning of Haleakalā is ingrained in the songs and stories of Maui that are passed down from generations.

“From when we’re born, we are singing songs, we learn the compositions that have been composed that include Haleakalā,” she said.

She draws from the wisdom of the ‘ōlelo no‘eau that says, “He ali‘i ka ‘āina; he kauwā ke kāne,” meaning that “the land is chief; man is its servant.”

Opposition to the solar telescope a decade ago showed “the people’s will to not have any more be put on Haleakalā,” Helm said. Proposing to build more “is an assault, I feel, on the health and well-being of our mountain, as well as our creatures, as well as our culture, as well as our people.”

“These people are trying to come from outside and trying to do something here on our island in the middle of the Pacific,” she said. “And we say, look elsewhere.”

For more information on the telescope project and hearings, or to provide public comment before the March 16 deadline, visit www.amosstareis.com.