UH leads Waikīkī sea-level rise renderings to adapt and elevate infrastructure, utilities

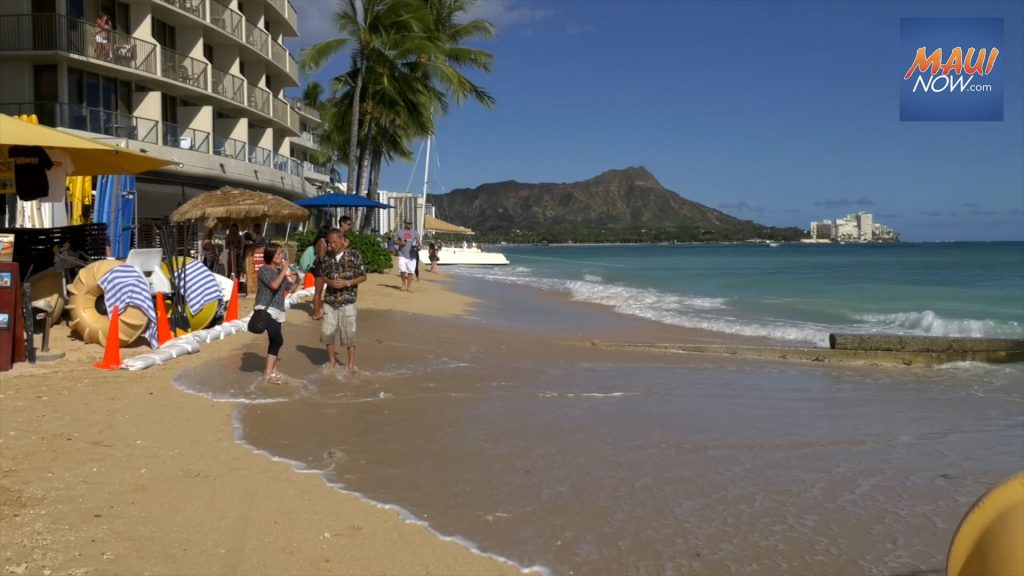

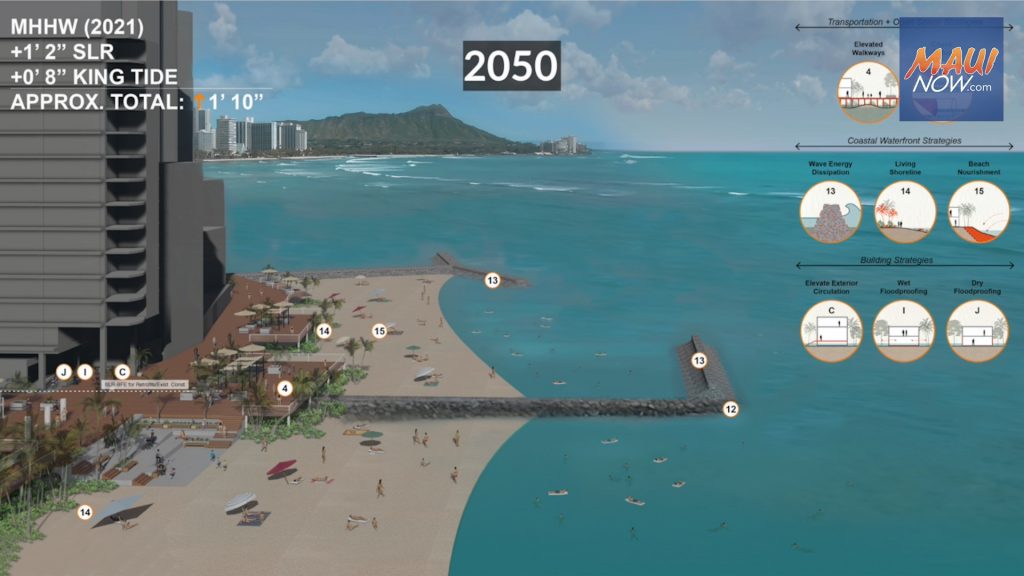

Sea level in Waikīkī is projected to rise up to about one foot by 2050 and nearly six feet by 2100 due to climate change, prompting University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa researchers to create architectural renderings that illustrate possible adaptation strategies.

The strategies that can also be used in other low-lying coastal cities include relocating critical equipment in buildings and streets, elevating utilities and walkways, and incorporating cisterns (water storage tanks) and bioretention areas (soil and plant-based filtration system in a landscaped depressions) to manage stormwater runoff.

With potential losses from sea-level rise projected to reach $19 billion in Hawaiʻi alone, protecting Waikīkī, a major economic hub generating $5 billion annually for the state, is crucial according to a UH news release. The research by principal investigator and UH Mānoa Associate Professor Wendy Meguro and her team research was published in Sustainability in March and a special issue of Oceanography in April.

“We’re looking at Waikīkī because it is an economic, recreational, and cultural hub,” said Meguro, director of the School of Architecture Environmental Research and Design Laboratory and the Hawaiʻi Sea Grant Center for Smart Building and Community Design. “But the process that we are using to visualize potential adaptation strategies and discuss them with the community should be replicable in other areas. Given the long lifespan of buildings or roadways, they will likely still exist in 50 years. The decisions we make today should anticipate the flooding that we will have 50 years from now.”

Public outreach surveys indicated that 79% of participants found the proposed strategies relevant and feasible for Waikīkī. Community involvement in the adaptation planning process was demonstrated through workshops, public presentations and surveys, engaging more than 700 stakeholders in 2021–2023.

“In public outreach events, we presented urban and architectural renderings that depicted a specific site and discussed how we might adapt, for example, by elevating a building,” said Meguro. “The renderings have been a key communication tool to initiate a coordinated conversation with many parties. And in our surveys, we’ve been able to get the public’s feedback on those strategies, and have found that people are really interested in elevating critical equipment, both in buildings and at the streetscape.”

“The research underscores academia’s role in supporting governmental and municipal efforts to address climate change,” according to Josephine Briones, a UH Mānoa climate adaptation specialist. By providing visualizations and engagement opportunities, the team has helped bridge the gap between scientific research and practical, community-driven solutions.

“The role of academia is important in addressing future responses to the effects of climate change, particularly sea-level rise in Hawaiʻi,” said Briones, “Academic research plays a pivotal role in illustrating potential future adaptation strategies in low-lying coastal communities and enhances local municipalities’ adaptation plans.”

Looking ahead, the team aims to build on their framework by continuing to integrate academic research, community input and policy planning. The project has been supported by multiple funding sources, including NOAA, Office of Naval Research, Hawai‘i Sea Grant and UH Climate Resilience Collaborative. Key contributors to the research include Chip Fletcher, Gerry Failano, Eric Teeples and Briones, along with other graduate students and specialists.