‘Wasted opportunity?’ Maui Council questions post-wildfire pivot on homeless plan

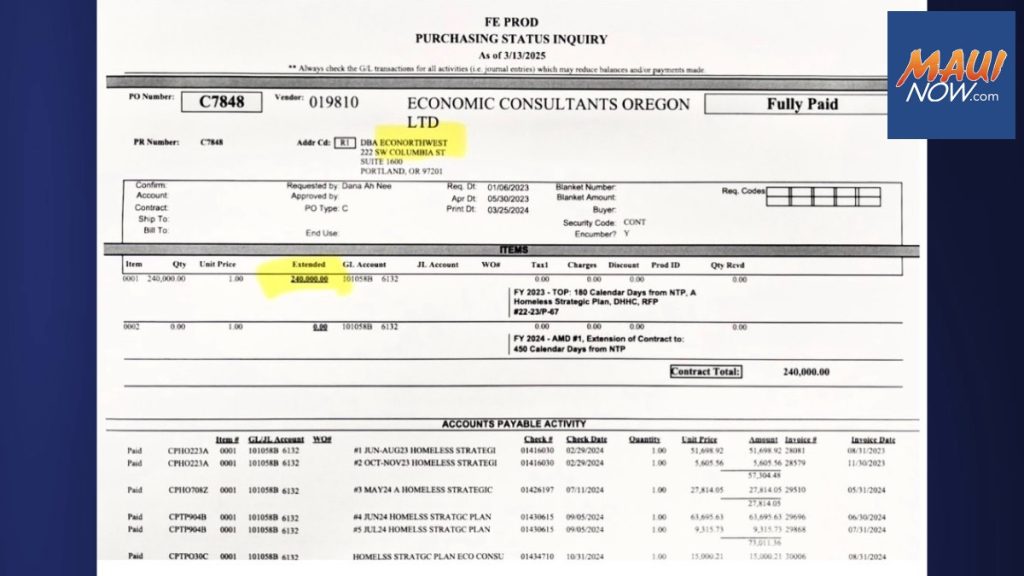

Maui County taxpayers spent $240,000 for a “homeless strategic plan,” but that’s not what they got.

On Monday, officials told Maui County Council members that the county’s all-hands-on-deck response to the devastating August 2023 wildfires made creating that plan “infeasible,” leading instead to a “community-informed report” titled “Recommendations to Address Homelessness in Maui County.”

Now, as the county’s housing critical housing shortage continues and homeless encampments crop up in secluded areas, Maui County Council members are questioning the legality of the change in homeless plan’s contracted scope of work. West Maui Council Member Tamara Paltin said a comprehensive homeless plan is needed “now more than ever” after the wildfires. The County’s $240,000 was “misspent,” she said, and a “huge opportunity” to diminish homelessness was “wasted.”

“I don’t think this was a good use of taxpayer funds,” Paltin said during a Council committee meeting Monday. “We were behind the curve, and now we’re even more behind the curve.”

She questioned the legality of changing the project’s scope of work “after the fact.”

A deputy corporation counsel said she’d research and respond to council members in writing as to whether shifting the homeless plan’s deliverable — after the project was underway — was in compliance with the state’s procurement code.

Portland, Ore.-based consultant ECOnorthwest‘s homeless recommendations report was the focal point of discussion during Monday’s meeting of the Maui County Council Water Authority, Social Services, and Parks Committee, chaired by Council Member Shane Sinenci.

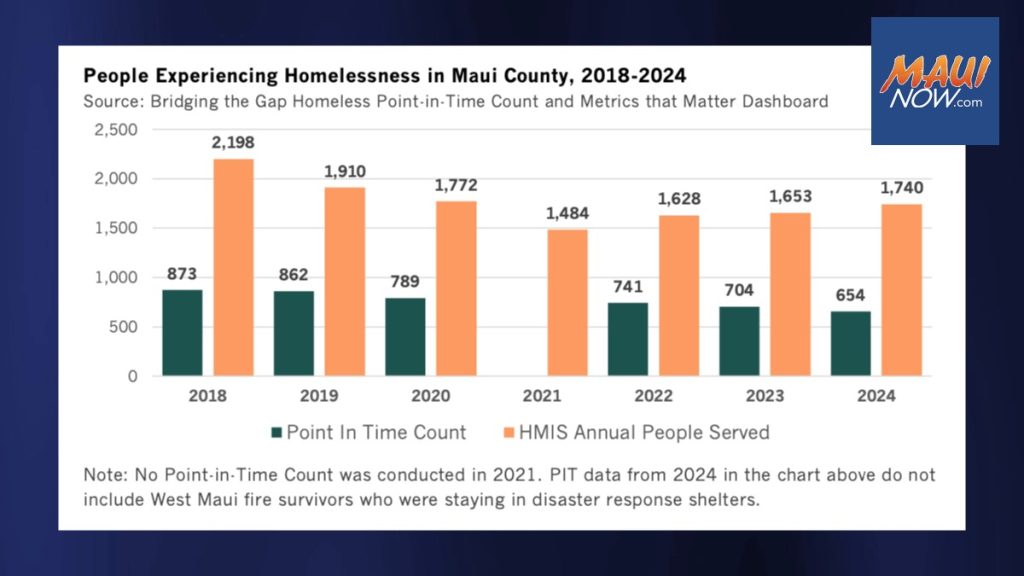

The report found that homelessness impacts Native Hawaiians disproportionately, compared with other groups in Maui County. Nearly 1 in 4 of people served by the homelessness support system were under the age of 18. And, while the number of unhoused people in the annual “Point in Time” Count had decreased, year over year, the number of people served by the homelessness system increased.

One of its main recommendations: “Effective coordination and collaboration among all actors within the homelessness support system ensures there are no gaps for people in crisis to fall through. People in crisis experience smooth transitions between different service providers with minimal traumatization or unnecessary duplicative assessments, paperwork and explanations.”

This morning, the University of Hawaiʻi Economic Research Organization released its updated Hawaiʻi Housing Factbook 2025. It reports that the scale of Hawaiʻi’s homeless crisis — already the highest in the nation (80.5 per 10,000 residents) because of exorbitant housing costs and poor mortgage affordability — has been intensified by the Maui wildfires. University economists said: “The wildfires provide a stark lesson: when housing supply shrinks, prices increase, residents leave, and homelessness grows.”

Maui contributed significantly to the 87% surge in the state’s homeless population in 2024, the economists report. The increase, documented by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, increased the number of homeless individuals statewide to 11,637, in large part because of the displacement of more than 5,000 people by the Lahaina wildfire.

On Monday, Department of Human Concerns Director Lori Tsuhako told committee members that the wildfires played a key role in the decision to change the ECOnorthwest project deliverables.

Before the wildfires, work was on course with the consultant to conduct the work to create a strategic homeless plan, but then “the fires occurred.”

She explained that she, then Deputy Director Saumalu Mataafa and Christopher Kish of the Homeless Division were all deployed to the Emergency Operations Center to assist with the County’s response to the wildfires and the disaster aftermath.

“We could not manage that process in addition to doing the work that we were doing,” Tsuhako said. “And so we asked to put a hold on ECOnorthwest work because we were not able to attend to them and do that work.”

Later, “we knew that there was a large population of people who were displaced by the fire,” she said. “And so part of the change in the scope was to really address and try to see if there were issues related specifically to the fire survivors that had an impact on our larger homeless population and issues around that.”

“That was the primary reason for the change in scope because of the circumstances of the fire and the ongoing attempt to have people housed afterwards,” she said.

Paltin responded, saying: “It seems that in the aftermath of the fire, we need a strategic plan more than ever. And the study is not necessarily doing anything to help our fire survivors who continue to have trouble now.”

Trouble has been brewing over homelessness for years, and concerns about the county’s approach to homelessness planning are not new. As far back as a May 2020 Council Affordable Housing Committee meeting, Council Member Alice Lee pressed officials, including Tsuhako, for concrete plans to increase housing units, with limited specifics offered at the time.

In April 2022, the Maui County Cost of Government Commission called for a comprehensive plan to end homelessness in Maui County. The commission’s recommendation was modeled after Maui County Council’s request for proposals in July 2020 for a “Comprehensive Affordable Housing Plan.”

The Cost of Government Commission studied Maui County’s homelessness extensively, and it provided an insight in an appendix to its report:

“There is a constant tension between those who want to exercise compassion to the unsheltered and immediately provide them with food, water, restrooms, showers and medical care, while they are still unhoused, and those who believe such actions merely encourage more and lengthier homelessness. The laudable policy of ‘Housing First’ is futile and cruel if there is not adequate and supportive housing immediately available. Despite years of hard work by the County’s Homeless Program and these dedicated nonprofits, that supply of adequate housing has not been created, and is not close to creation.”

Mike Williams, chair of the Cost of Government Commission at the time it studied homelessness and called for a comprehensive plan, said the ECOnorthwest report and was “extremely disappointed.”

“I was also disappointed by the fact that the county administration didn’t insist on a plan,” he said.

William said the Cost of Government Commission’s report in 2022 listed all the elements that members thought should be in a strategic homeless plan, “and almost none of those were covered in the report.”

“I’m not sure if its the consultant’s fault or the administration’s fault, but we didn’t get a plan, and that’s a real problem,” he said.

On Tuesday, Williams said he’s frustrated that there wasn’t a plan to end homelessness in 2020, or in 2022, when the commission issued its report. Now, “here we are three years later, and we still don’t have a plan. You know, to me, it’s just a shameful part of the situation that we have all these homeless people, and we have the ability to take care of them, and we don’t.”

Williams said he thinks Maui County should construct tiny homes in a program akin to Gov. Josh Green’s signature kauhale initiative, which provides small shelters and support programs to homeless people.

Maui could have 50 to 150 kauhale structures to provide a secure space and permanent home for people without shelter. The units would include kitchen and laundry facilities, he said.

“We need to decide where to put them,” he said.

Williams said he also believes the Homeless Division should be removed from the Department of Human Concerns and put into the new Department of Housing.

“The Department of Human Concerns has had the homeless program now for the six years since I’ve been watching, and they haven’t done anything,” he said. “They haven’t advanced a single new initiative to try to improve the homeless situation on this island.”

“I understand that Oʻahu already has 16 kauhale operating, and we don’t have a single one yet,” Williams said.

Now it’s common knowledge that Maui’s housing crisis has worsened since 2022, especially after the wildfires destroyed more than 2,200 structures, most of them homes. The disaster left thousands of people without housing. Those unable to find temporary shelter were homeless. To make matters worse, the Ka Hale A Ke Ola Homeless Resource Center lost its 78-unit West Maui shelter during the wildfire.

In an April 11 letter, responding to questions from Sinenci, Tsuhako said the ECOnorthwest report met the “bare minimum” of contractural requirements.

Sinenci also asked Tsuhako whether the Department of Human Concerns would “take the lead in increasing coordination and collaboration” among organizations “that interact with unhoused and housing insecure people in Maui County.”

In her letter, Tsuhako said: “The department has consistently worked to increase collaboration and coordination between organizations who serve the houseless populations,” adding details about training groups of providers to help them understand “the larger system of care and how permanent housing resources are funded and accessed.”

Tsuhako also affirmed her department’s commitment to “Housing First” principles.

“The department is aligned with a Housing First model, an internationally recognized evidence-based practice that remains a foundational strategy of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, which provides the lion’s share of funding for housing chronically homeless individuals and families,” she said. “One challenge of achieving a higher level of coordination among our varied service providers is that not all providers are aligned with nor understand HUD’s strategies.”

“Our department’s goal is to end homelessness of individuals by permanently housing them and providing services as requested to maintain tenancy,” Tsuhako said. “Some service providers are more focused on supporting encampments and have at times interfered with other providers’ efforts to end the homelessness of individuals and families. This disparity in mission/goals may hopefully be reduced by expanding discussion and providing road maps where common ground can be found.”

Paltin told Maui Now that the County’s “Housing First” policy hasn’t worked for years. And, she said, there are people who refuse help or refuse placement in housing. “If we can just not include everyone who refuses housing, then it’s not really addressing the problem, and the data doesn’t match what people are seeing,” she said.

Some people feel unsafe in congregate housing settings, fear being assaulted; or they’re unable to keep their pets, such as dogs, Paltin said.

During Monday’s committee meeting, Chair Sinenci asked ECOnorthwest Project Director Cadence Petros what led to the contractor’s decision to change to a “consensus model, instead of a strategic plan.”

Petros said the “decision to pivot from a kind of consensus-based strategic plan to a community informed recommendations report was jointly made by county staff and our project team.” She later specified that “county staff” meant the Department of Human Concerns, Director Tsuhako and Kish of the Homeless Division.

Petros explained that, at the time of the wildfires, one team member was on the island and others were en route to Maui when “we learned that the island was on fire.” Her team had planned “for a week of engagement with people with lived experience with service providers, interviews.”

Instead, they went back to the Mainland, and they were “on pause.” Then, in October 2023, the team learned the project “was not dead,” but that “circumstances had changed.” She said her team had already “spent a fairly significant amount of our budget trying to ramp up for the first part of the engagement that was unable to occur.”

Petros said her team then worked with the County to “essentially refine” the project scope. They needed to consider a “whole new cohort of unhoused folks” after the wildfires, in addition to people who were experiencing homelessness before that.

That led to the decision to do a “community-informed recommendations report” instead of a “consensus-based strategic plan.” Petros said she was told it would be “infeasible” to proceed with a strategic plan.

The original intent of Maui County’s request for proposals for the project was clear from the title page: it was to be a “Homeless Strategic Plan.” The objective of the RFP was to “provide a roadmap for Maui County to decrease the number of homeless individuals and households by ending their homelessness while utilizing a housing-focused approach.”

Part of the task of the contractor, according to the County’s RFP, was to “develop measurable goals and strategies with clear timelines.” It said the plan should address the six-year period from 2023-2029, and identify timelines for achieving key objectives.

The RFP said the community should be engaged and empowered to be “part of the solution.”

And, the contractor was to “develop strategies to address encampments that are housing-focused, sensitive to individual’s civil rights, with conscious consideration for public safety, public health, and environmental impacts.”

The Council committee did not take any legislative action.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated from its original version to include an update on Hawaiʻi’s housing crisis and homelessness from the University of Hawaiʻi Economic Research Organization.

_1768613517521.webp)